|

.

"At Jena, the Prussian army performed the finest

and most spectacular maneuvers, but I soon put

a stop to this tomfoolery and taught them that

to fight and to execute dazzling maneuvers and

wear splendid uniforms were very different matters."

- Napoleon

|

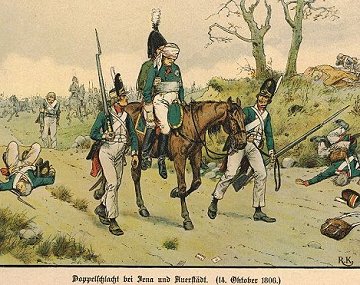

Decline of the Army: defeats at Jena and Auerstadt

[by 1806] The Prussian Army, however, remained rooted in the past:

a fossil preserved in Baltic amber."- Charles Summerville

In 1806 Napoleon was very interested in the Prussian army.

Officer Chlapowski of Napoleon's

Guard Lancers writes: "... the Emperor asked me about very many things. He fired questions at me as if I was sitting an exam. He already knew from our conversations ... that I had served in the Prussian amry, so he asked about my studies there, about my military instructors, about the organization of the artillery and of the whole Prussian army, and finally he asked how many Poles were likely to be in the corps which was still in East Prussia beyond the Vistula under General Lestoq. I could not answer this question but pointed out that most of his corps must be Lithuanians, as it had been mainly recruited in Lithuania. At that time, since the last partition [of Poland] the whole district of Augustow belonged to Prussia.

I also explained that in Lithuania only the gentry were Polish, and the people Lithuanians. He did not know anything about Lithuania ... The Emperor listened patiently and carefully to all these details. ... [he] asked me about the [Prussian] military academies. How far did they go in the study of mathematics ? He was surprised at the elementary level at which they stopped. Didn't they teach applied geometry ? I myself had not learned this, but only later studied it in Paris." (Chlapowski/Simmons - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p 12-13)

In 1806 the Prussian army consisted of 200,000 men: 133,000 infantrymen, 39,600 cavalrymen and 10,000 artillerymen and few thousands of engineers, garrisons, reserves etc.

Infantry

. . . . . . . . . 2 Guard infantry regiments (2 battalions each)

. . . . . . . . . 58 infantry regiments (2 battalions each)

. . . . . . . . . 1 jager regiment (3 battalions)

. . . . . . . . . 27 grenadier battalions

. . . . . . . . . 24 fusilier battalions

Cavalry

. . . . . . . . . 13 cuirassier regiments (5 squadrons each)

. . . . . . . . . 14 dragoon regiments (10 x 5 squadrons and 2 x 10 squadrons)

. . . . . . . . . 9 hussar regiments (10 squadrons each)

. . . . . . . . . 1 'Towarzysze' regiment (10 + 5 squadrons)

Artillery

. . . . . . . . . 4 foot artillery regiments (36 12pdr batteries of 8 guns)

. . . . . . . . . 1 horse artillery regiment (20 6pdr batteries of 8 guns)

. . . . . . . . . reserve (2 10pdr mortar batteries, 1 light mortar battery, 4 7pdr howitzer batteries

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 6pdr batteries)

Napoleon was not impressed with the king of Prussia: "When I went to see the king of Prussia

Friedrich Wilhelm III, instead of a library I found he had a large room, like an arsenal, furnished with shelves and pegs, in which were placed fifty or sixty jackets of various cuts ...

He attached more importance to the cut of a dragoon or a hussar uniform than would have

been necessary for the salvation of a kingdom. At Jena, his [Prussian] army performed the

finest and most spectacular maneuvers, but I soon put a stop to this tomfoolery and taught

them that to fight and to execute dazzling maneuvers and wear splendid uniforms were very

different matters. If the French army had been commanded by a tailor, the king of Prussia

would certainly have gained the day."

Napoleon's efforts to get Prussia to close its ports to British goods in 1806 had revealed a problem. When Prussia agreed, the British navy retaliated by seizing 700 Prussian merchant ships in port or at sea and blocking their access to the North Sea. Facing economic collapse, the Prussian king then turned his anger on Napoleon, rescinding their agreements and ordering the French out.

That in turn led to war.

"When in August 1806, Prussia mobilized her army for a war against France, she did with all the confidence that was due

to the inheritors of the traditions of Frederick the Great. There was never a moment of doubt that Prussian

arms would triumph, and it was with this attitude, that her soldiers met the French in the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt on October 14."

"When in August 1806, Prussia mobilized her army for a war against France, she did with all the confidence that was due

to the inheritors of the traditions of Frederick the Great. There was never a moment of doubt that Prussian

arms would triumph, and it was with this attitude, that her soldiers met the French in the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt on October 14."

Up to that time, the Prussian Army had proudly reflected the image of Frederick's glory, but it was this in itself

which was one of the principal defects in the military system. A cult of reverence, in regard to anything that was

connected with Frederick, dominated military thought.

Any measure which had sufficed under the Great Soldier-King, was considered good enough for his heirs, irrespective of the forward movement of

military science and the revolutionary principles of warfare, which had been demonstrated in Europe since 1792.

Tradition was clung to as if it were a means to glory and success.

The fact that the 1780 pattern of musket was one of the worst in Europe,

or that the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of Brunswick, and the Senior Royal

Advisor, von Mollendorf, were not the men they had been, was little considered.

The state of the Prussian Army at that time was well summed up by Clausewitz when he remarked that

'... for Prussia, the cost of anachronism was to be high."

( - David Nash - "The Prussian Army 1808-15" p 5)

Prussian order of battle: Jena 1806 (Saxons excluded)

Commander: GL von Ruchel

(GL General-Lieutenant , GM General-Major)

Advance Guard

- GL von Winning |

Main Body |

Light Brigade

- - - - - Jager Company

- - - - - 27th Infantry Regiment [2 battalions]

- - - - - half of 7th Hussar Regiment [5 squadrons]

- - - - - half of XIX 6pdr Foot Battery

Light Brigade

- - - - - Jager Company

- - - - - I and II Fusilier Battalion

- - - - - 3rd Hussar Regiment [10 squadrons]

- - - - - half of XI 6pdr Horse Battery

.

.

.

.

.

|

Infantry Brigade

- - - - - 9th Infantry Regiment [1 battalion]

- - - - - 23rd Infantry Regiment [1 battalion]

- - - - - X Grenadier Battalion

Infantry Brigade

- - - - - 29th Infantry Regiment [1 battalion]

- - - - - 43rd Infantry Regiment [1 battalion]

- - - - - IX Grenadier Battalion

Infantry Brigade

- - - - - 10th Infantry Regiment [2 battalions]

- - - - - 37th Infantry Regiment [2 battalions]

- - - - - XVIII Fusilier Battalion

Cavalry Brigade

- - - - - 5th Cuirassier Regiment [5 squadrons]

- - - - - 4th Dragoon Regiment [5 squadrons]

- - - - - half of 7th Hussar Regiment [5 squadrons]

Artillery

- - - - - 12pdr Foot Battery

- - - - - half of XIX 6pdr Foot Battery

- - - - - half of 6pdr Foot Battery

- - - - - half of XI 6pdr Horse Battery

|

The French army, honed to a fine edge by the brilliantly conducted previous campaign in Bavaria and Austria, secured the total annihilation of the

Prussian army and state in precisely one month, from October 6 to November 6.

It was a remarkable demonstration of what the French military system could accomplish under Napoleon's guidance.

Prussia was broken and dismembered by the war.

Her army was ruined, she had no money, and she had lost half of her former possessions.

Napoleon's plan of this campaign was beautiful.

To base himself on the Rhine River and Upper Danube and simply advance north -

eastwards on Berlin would, perhaps, be the easiest for Napoleon, but it would offer no strategical advantages; for if he met and defeated the

Prussians on this west-east line, he would simply drive them backwards on their supports, and then on Russians, whose advance

from Poland was expected.

To turn the Thuringian Forest Mountains by an advance from his right, was a less

safe movement; but, it offered great advantages.

To turn the Thuringian Forest Mountains by an advance from his right, was a less

safe movement; but, it offered great advantages.

First of all Napoleon would threaten the Prussian supply lines, line of retreat, and line of communications with Berlin.

Secondly, Napoleon would separate the Prussians and the advancing strong Russian Army.

The danger with this maneuver was this that the Prussians by a rapid advance through the Thuringian Forest Mountains

against his communication line, might sever him from France !

In the last days of September the Prussian army was spread over a front of 190 miles.

The Saxons had not yet completed their mobilisation. Within few days the Prussians shortened their front

to 85 miles in a direct line. At the same time Napoleon had huge army already assembled on a front of 38 miles.

At last Napoleon's real plan had dawned on the Prussian headquarters. Advance guards were sent in the

direction of the Thuringian Forest. The Prussians also detached small corps from Ruchel's

force against Napoleon's supply lines. By doing this they weakened their own

main army.

Heavy fighting began when elements of Napoleon's main force encountered Prussian troops near Jena.

The Battle of Jena cost Napoleon approx. 5,000 men, but the Prussians had a staggering 25,000 casualties.

Heavy fighting began when elements of Napoleon's main force encountered Prussian troops near Jena.

The Battle of Jena cost Napoleon approx. 5,000 men, but the Prussians had a staggering 25,000 casualties.

At Auerstadt Marshal Davout's also crushed the enemy.

Napoleon initially did not believe that Davout's single corps had defeated the Prussian main body unaided,

and responded to the first report by saying "Tell your Marshal he is seeing double". As matters became clearer,

however, the Emperor was unstinting in his praise.

"The whole campaign was epitomised by the surrender of Hohenlohe's army at Prenzla, where Murat was able to bluff a vastly superior force into laying down its arms. Twenty-nine thousand men under L'Estocq managed

to link up with the Russian army in East Prussia, but by the end of November 1806, the majority of the Prussian Army had surrendered and Frederick the Great's sword and sash were on their way to Les Invalides as trophies. The basic material of the old army, the private soldier, was sound, but internal weaknesses had meant that the Prussian army was out-thought as

well as outfought." (Robert Mantle - "Prussian Reserve Infantry: 1813-15")

"The whole campaign was epitomised by the surrender of Hohenlohe's army at Prenzla, where Murat was able to bluff a vastly superior force into laying down its arms. Twenty-nine thousand men under L'Estocq managed

to link up with the Russian army in East Prussia, but by the end of November 1806, the majority of the Prussian Army had surrendered and Frederick the Great's sword and sash were on their way to Les Invalides as trophies. The basic material of the old army, the private soldier, was sound, but internal weaknesses had meant that the Prussian army was out-thought as

well as outfought." (Robert Mantle - "Prussian Reserve Infantry: 1813-15")

Peter Hofschroer gives three main reasons for why Prussia was defeated in 1806.

Not joining Austria and Russia in 1805 in the Third Coalition. This combination would most likely have led to Napoleon's defeat.

Going to war against France in 1806 without the direct support of another great power.

The Prussian army should have adopted a defensive strategy until the arrival of the Russians.

Dividing the army into three in the face of the enemy.

Nobody was really in charge and King Frederick William III lacked the authority to impose his will.

"... just after the victories of Jena and Auerstadt, in which Napoleon destroyed the Prussian army and shook the Prussian state to its core, was to be something of a turning point. The Prussians were shocked and insulted by the French victories, but they also saw them as proof of the superiority of France and her political culture.

"... just after the victories of Jena and Auerstadt, in which Napoleon destroyed the Prussian army and shook the Prussian state to its core, was to be something of a turning point. The Prussians were shocked and insulted by the French victories, but they also saw them as proof of the superiority of France and her political culture.

When Napoleon rode into Berlin he was greeted by crowds which, according to one French officer, were as enthusiastic as those that had welcomed him in Paris on his triumphant return from Austerlitz the previous year. 'An undefinable feeling, a mixture of pain, admiration and curiosity agitated the crowds which pressed forward as he passed,' in the words of one eyewitness ...

Napoleon treated Prussia and her King worse than he had treated any conquered country before.

At Tilsit he publicly humiliated Frederick by refusing to negotiate with him, and by treatening Queen Louise, who had come in person to plead her country's cause, with insulting gallantry. He did not bother to negotiate, merely summoning the Prussian Minister Goltz to let him know his intentions. He told the Minister that he had thought of giving the throne of Prussia to his own brother Jerome, but out of regard for Tzar Alexander, who had begged him to spare Frederick, he had graciously decided to leave him in possession of it. But he diminished his realm by taking away most of the territory seized by Prussia from Poland ... "

(Zamoyski - "Moscow 1812" p 43)

|

In 1226 Polish Duke, Konrad I, invited the Teutonic Knights, a German military order of crusading knights headquartered in Acre, to conquer the Baltic tribes on his borders.

However, during 60 years of struggles against the Old Prussians, the Teutonic Knights created an independent state which came to control Prussia.

The Knights were eventually defeated by Polish troops at Grunwald (1410) and were forced to acknowledge the sovereignty of the Polish king Casimir IV Jagiellon in the Peace of Thorn in 1466, losing western Prussia to Poland in the process.

In 1226 Polish Duke, Konrad I, invited the Teutonic Knights, a German military order of crusading knights headquartered in Acre, to conquer the Baltic tribes on his borders.

However, during 60 years of struggles against the Old Prussians, the Teutonic Knights created an independent state which came to control Prussia.

The Knights were eventually defeated by Polish troops at Grunwald (1410) and were forced to acknowledge the sovereignty of the Polish king Casimir IV Jagiellon in the Peace of Thorn in 1466, losing western Prussia to Poland in the process.

Frederick William went to Warsaw in 1641 to render homage to King Wladyslaw IV Vasa of Poland for the Duchy of Prussia, which was still held in fief from the Polish crown.

Frederick William went to Warsaw in 1641 to render homage to King Wladyslaw IV Vasa of Poland for the Duchy of Prussia, which was still held in fief from the Polish crown.

"The aggrandizement of Prussia continued under Frederick's grandson, Frederick II, the 'Great' who enlarged his domain with territories plundered from the ancient Kingdom of Poland. This trend continued unabated until 1795, when Poland literally disappeared off the map: gobbled up by her three powerful neighbours, Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

"The aggrandizement of Prussia continued under Frederick's grandson, Frederick II, the 'Great' who enlarged his domain with territories plundered from the ancient Kingdom of Poland. This trend continued unabated until 1795, when Poland literally disappeared off the map: gobbled up by her three powerful neighbours, Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

In 1740s Prussia owned 85.000 troops which gave her the 4th largest army in Europe, even though her lands stood at 10th in order of size and only 13th in population !

In 1740s Prussia owned 85.000 troops which gave her the 4th largest army in Europe, even though her lands stood at 10th in order of size and only 13th in population !

Frederick the Great imposed so spartan discipline that 400 officers "are said to have asked to resign". Frederick's troops fought with great success against the Russians, French, Germans, Swedes and Austrians.

Frederick the Great imposed so spartan discipline that 400 officers "are said to have asked to resign". Frederick's troops fought with great success against the Russians, French, Germans, Swedes and Austrians.

1757 Battle of Rossbach. The French commander, Marshal Prince de Soubise (54,000 men), was not over-anxious to measure his

strength with Frederick the Great, but his generals were eager for battle and confident of

success. Their only doubt was whether they could win any glory by destroying so small Prussian force (22,000 men); their only fear lest he should retreat and escape them.

1757 Battle of Rossbach. The French commander, Marshal Prince de Soubise (54,000 men), was not over-anxious to measure his

strength with Frederick the Great, but his generals were eager for battle and confident of

success. Their only doubt was whether they could win any glory by destroying so small Prussian force (22,000 men); their only fear lest he should retreat and escape them.

Map of Europe in 1756.

Prussia's allies were: Britain, Brunswick, Hannover, and Hesse-Kassel.

Map of Europe in 1756.

Prussia's allies were: Britain, Brunswick, Hannover, and Hesse-Kassel.

Frederick William III of Prussia succeeded the throne in 1796. He married Louise of Mecklenburg, a princess noted for her beauty.

Napoleon dealt with Prussia very harshly, despite the pregnant Queen's personal interview with the French emperor. Prussia lost all its Polish territories, as well as all territory west of the Elbe River, and had to pay for French troops to occupy key strong points within the Kingdom. Too distrustful to delegate his responsibility to his ministers, Frederick William was too infirm of will to strike out and follow a consistent course for himself.

In the following years the reformers encouraged Friedrich Wilhelm's interest in designing the new uniforms to keep him from interfering with their more radical measures.

Frederick William III of Prussia succeeded the throne in 1796. He married Louise of Mecklenburg, a princess noted for her beauty.

Napoleon dealt with Prussia very harshly, despite the pregnant Queen's personal interview with the French emperor. Prussia lost all its Polish territories, as well as all territory west of the Elbe River, and had to pay for French troops to occupy key strong points within the Kingdom. Too distrustful to delegate his responsibility to his ministers, Frederick William was too infirm of will to strike out and follow a consistent course for himself.

In the following years the reformers encouraged Friedrich Wilhelm's interest in designing the new uniforms to keep him from interfering with their more radical measures.

"When in August 1806, Prussia mobilized her army for a war against France, she did with all the confidence that was due

to the inheritors of the traditions of Frederick the Great. There was never a moment of doubt that Prussian

arms would triumph, and it was with this attitude, that her soldiers met the French in the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt on October 14."

"When in August 1806, Prussia mobilized her army for a war against France, she did with all the confidence that was due

to the inheritors of the traditions of Frederick the Great. There was never a moment of doubt that Prussian

arms would triumph, and it was with this attitude, that her soldiers met the French in the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt on October 14."

To turn the Thuringian Forest Mountains by an advance from his right, was a less

safe movement; but, it offered great advantages.

To turn the Thuringian Forest Mountains by an advance from his right, was a less

safe movement; but, it offered great advantages.

Heavy fighting began when elements of Napoleon's main force encountered Prussian troops near Jena.

The Battle of Jena cost Napoleon approx. 5,000 men, but the Prussians had a staggering 25,000 casualties.

Heavy fighting began when elements of Napoleon's main force encountered Prussian troops near Jena.

The Battle of Jena cost Napoleon approx. 5,000 men, but the Prussians had a staggering 25,000 casualties.

"The whole campaign was epitomised by the surrender of Hohenlohe's army at Prenzla, where Murat was able to bluff a vastly superior force into laying down its arms. Twenty-nine thousand men under L'Estocq managed

to link up with the Russian army in East Prussia, but by the end of November 1806, the majority of the Prussian Army had surrendered and Frederick the Great's sword and sash were on their way to Les Invalides as trophies. The basic material of the old army, the private soldier, was sound, but internal weaknesses had meant that the Prussian army was out-thought as

well as outfought." (Robert Mantle - "Prussian Reserve Infantry: 1813-15")

"The whole campaign was epitomised by the surrender of Hohenlohe's army at Prenzla, where Murat was able to bluff a vastly superior force into laying down its arms. Twenty-nine thousand men under L'Estocq managed

to link up with the Russian army in East Prussia, but by the end of November 1806, the majority of the Prussian Army had surrendered and Frederick the Great's sword and sash were on their way to Les Invalides as trophies. The basic material of the old army, the private soldier, was sound, but internal weaknesses had meant that the Prussian army was out-thought as

well as outfought." (Robert Mantle - "Prussian Reserve Infantry: 1813-15")

"... just after the victories of Jena and Auerstadt, in which Napoleon destroyed the Prussian army and shook the Prussian state to its core, was to be something of a turning point. The Prussians were shocked and insulted by the French victories, but they also saw them as proof of the superiority of France and her political culture.

"... just after the victories of Jena and Auerstadt, in which Napoleon destroyed the Prussian army and shook the Prussian state to its core, was to be something of a turning point. The Prussians were shocked and insulted by the French victories, but they also saw them as proof of the superiority of France and her political culture.

Under the noses of French spies Prussia developed a reserve army capable of taking the field.

Under the noses of French spies Prussia developed a reserve army capable of taking the field.

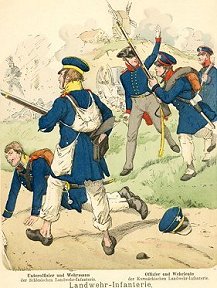

The landwehr in Prussia was first formed by a royal edict of 17 March 1813, which called up all men capable of bearing arms between the ages of 18 and 45, and not serving in the regular army, for the defence of the country.

The landwehr in Prussia was first formed by a royal edict of 17 March 1813, which called up all men capable of bearing arms between the ages of 18 and 45, and not serving in the regular army, for the defence of the country.

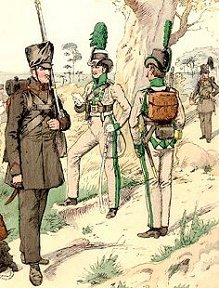

Left: Lutzow's Free Corps in 1813-15. Picture by Knotel.

Left: Lutzow's Free Corps in 1813-15. Picture by Knotel. At Waterloo the Prussians had 38,000 infantry in 62 battalions, 7,000 cavalrymen in 61

squadrons, and 134 guns. Total of 50,000 men arriving in different times on the battlefield.

The troops were led by seasoned officers and generals. "That the morale of the majority of

the Prussian army withstood the rigours of the field and the shock of Ligny was due to the

high quality of leadership at all levels. " (Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 208)

At Waterloo the Prussians had 38,000 infantry in 62 battalions, 7,000 cavalrymen in 61

squadrons, and 134 guns. Total of 50,000 men arriving in different times on the battlefield.

The troops were led by seasoned officers and generals. "That the morale of the majority of

the Prussian army withstood the rigours of the field and the shock of Ligny was due to the

high quality of leadership at all levels. " (Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 208)

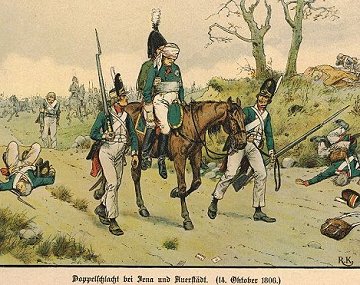

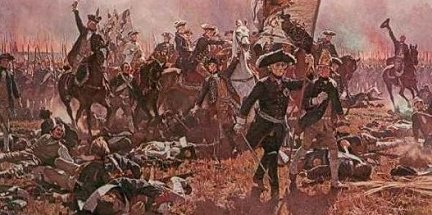

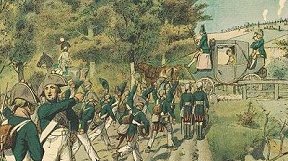

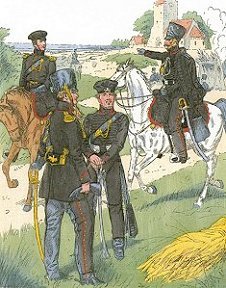

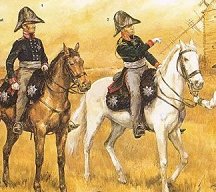

Picture: Chief-of-Staff of the Prussian Army (Napoleonic Wars),

General von Gneisenau, on white horse, and a staff officer.

By Christa Hook.

Picture: Chief-of-Staff of the Prussian Army (Napoleonic Wars),

General von Gneisenau, on white horse, and a staff officer.

By Christa Hook.