It may now be allowed the Author to give his opinion

on Buonaparte's plan of operation in this much-discussed

campaign.

Buonaparte determined to conduct and terminate the war in Russia as he had so many others. To begin with

decisive battles, and to profit by their advantages; to gain others still more decisive, and thus to go on playing double or quits

till he broke the bank - this was his manner; and we must admit that to this manner he owed the enormous success of his career, and that the attainment of such success was scarcely conceivable in any other manner.

In Spain it had failed. The Austrian campaign of 1809 had saved Spain by hindering him from driving the English

out of Portugal. He had since subsided there into a defensive war, which cost him prodigious exertions and, to

a certain extent, lamed him on one arm. It is extraordinary, and perhaps the greatest error he ever

committed, that he did not visit the Peninsula in person in 1810 in order to end the war in Portugal, by which that in Spain would be degrees have been extinguished; for the Spanish insurrection and the Anglo-Portuguese struggle

incontestably fomented each other. Buonaparte would however have been always compelled to leave

a considerable army in Spain.

It was naturally, and also very justly, a main object with him, in the case of this new war, to avoid being involved

in a similarly tedious and costly defensive struggle upon a theatre so much more distant. He was then under a pressing necessity of ending the war in, at the most,

two campaigns.

To beat the enemy, to shatter him, to gain the capital, to drive the government into the last corner of the empire and then, while the confusion was fresh,

to dictate a peace - had been hitherto the plan of operation in his wars.

(- p 144)

In the case of Russia, he had against him the prodigious extent of the empire, and the circumstance of its having

two capitals [Moscow and St.Petersbourg] at a great distance from each other.

... If Buonaparte was really obliged to calculate on ending the war in two campaigns, it then made

a great difference whether he conquered Moscow or not in the first. This capital once taken, he might hope to undermine

preparations for further resistance by imposing with the force which he had remaining - to mislead public

opinion - to set feeling at variance with duty.

If Moscow remained in the hands of the Russians, perhaps a resistance for the next campaign might form itself on

that basis to which the necessarily weakened force of Buonaparte would be unequal. In short, with the

conquest of Moscow, he thought himself over the ridge. This has always appeared to us the natural view

for a man like Buonaparte. The question arises, whether this plan was altogether impracticable, and whether there was not another

to be preferred to it ? We are not of such opinion.

The Russian army might be beaten, scattered. Moscow might be conquered in one campaign, but we are of opinion that

one essential condition was wanting in Buonaparte's execution of the plan - this was to remain formidable after the

acquisition of Moscow. We believe that this was neglected by Buonaparte only in consequence

of his characteristic negligence in such matters. He reached Moscow with 90,000 men; he should have reached

it with 200,000. This would have been possible if he had handled his army with more care and forbearance.

(- p 145)

The Russian army might be beaten, scattered. Moscow might be conquered in one campaign, but we are of opinion that

one essential condition was wanting in Buonaparte's execution of the plan - this was to remain formidable after the

acquisition of Moscow. We believe that this was neglected by Buonaparte only in consequence

of his characteristic negligence in such matters. He reached Moscow with 90,000 men; he should have reached

it with 200,000. This would have been possible if he had handled his army with more care and forbearance.

(- p 145)

He would, perhaps, have lost 30,000 men fewer in action if he had not chosen on every occasion to take the bull by the horns.

... Whether 200,000 men placed in the heart of the Russian empire would have produced the requisite moral effect, and commanded a peace, is certainly still a question, but it seems to us that it was allowable to reason a priori to that effect.

It was not to be anticipated with certainty that the Russians would desert and destroy the city, and enter upon a war of extermination;

perhaps it was not probable. If they were to do so, however, the whole object of the war was frustrated, carry it on as he would.

It is moreover to be considered as a great neglect on the part of Buonaparte to have made so little preparation as he did for retreat.

If Vilna, Minsk, Polotzk, Witebsk and Smolensk had been strengthened with works and sufficient pallisades,

and each garrisoned with from 5,000 to 6,000 men, the retreat would have been facilitated in more than one respect, especially in the matter of subsistence.

... If we consider that the army would also have both reached and quitted Moscow in greater force, we may conceive that the

retreat would have lost its character of utter destruction.

What then was the other plan which has been put forward after the event, as the more judicious or, as its advocates term it, the

more methodical ?

According to this, Buonaparte should have halted on the Dnieper and Dvina, should at furthest have concluded his campaign with the

occupation of Smolensk, should then have established himslef in the territory he had acquired, have secured his flanks, acquiring thereby a better base, have brought the Poles under arms, increasing his offensive strength, and thus for the

next campaign have secured the advantage of a better start, and arrived in better wind at Moscow.

This sounds well, if not closely examined, and especially if we omit to compare it with the views entertained by Buonaparte in

adopting the other plan. (- p 145)

This implies a conclusion of the campaign without a victory over the Russian army, which was to remain to

a certain extent intact, and Moscow not threatened. The Russian military, weak at the commencement, and certain to be nearly

doubled in the progress of hostilities, would have had time to complete its strength and then, in the course of the winter, to commence the

offensive against the enormously extended line of the French. This was no part in Buonaparte's taste of play.

Its worst feature was that a victory in the field, if he could gain one, remained without positive effect; since, in the middle of winter,

or even late autumn, he could devise no further operation for his victorious troops, no object on which to direct them.

He could then do nothing more than parry without thrusting in return.

Then the details of execution ! How was he to dispose his army ?

In quarters ? That fpor corps of moderate strength was only possible in the vicinity of large towns.

Encamp them ? Impossible in winter. Had he, however, concentrated his forces in single towns,

the intervening country was not his own, but belonged to the Cossacks.

The losses which the army would have suffered in the course of such a winter could not

probably have been replaced by arming the Poles.

This armament, if investigated, presented great difficulties.

First were excluded from it the Polish provinces in possession of Austria; next, those remaining in possession of Russia.

On Austria's account, also, it could not be conducted in the sense in which the

Poles could alone desire it; namely, the restoration of the old

Polish kingdom. This lamed the enthusiasm.

The main difficulty however that a country which has been pressed upon by enormous military and foreign masses

is not in a condition to make great military exertions. Extraordinary efforts on the part of the citizens of a state have their limits;

if they are called for in one direction, they cannot be available in another.

If the peasant be compelled to remain on the road the entire day with his cattle, for the transport of the supplies of an army, if he has his house full of soldiers,

if the proprietor must give up his stores for the said's army subsistence, when the first necessities are hourly

pressing and barely provided for, voluntary offerings of money, money's worth, and personal service are hardly to be looked for.

(- p 147)

Concede we, nevertheless, the possibility that such a campaign might have fulfilled its object, and prepared the way for a further

advance in the following season. Let us, however, remember what we have to consider on the other side - that Buonaparte found the Russians but half-prepared, that he could throw upon

them an enormous superiority of force, with a fair prospect of forcing a victory, and giving

to the execution of his undertaking the rapidity necessary for a surprise, with all but the certainty

of gaining Moscow at one onset, with the possibility of having a peace in his pocket within a quarter of a year.

Let us compare these views and reflections with the results of a so-called methodical campaign; it will be very doubtful,

all things compared, whether Buonaparte's plan did not involve greater probability of final success than the other, and in this case it was, in fact,

the methodical one, and the least audacious and hazardous of the two.

However this may be, it is easy to understand that a man like Buonaparte did not hesitate

between them. ...

(- p 148)

The famous conqueror in question was so far from deficient in this quality that he would have chosen the

most audacious course from inclination, even if his genius had not suggested it to him as the

wisest. We repeat it. He owed everything to this boldness of determination,

and his most brilliant campaigns would have been exposed to the sam imputations as have attached to the one we have described, if they had not succeeded.

(- p 148)

The famous conqueror in question was so far from deficient in this quality that he would have chosen the

most audacious course from inclination, even if his genius had not suggested it to him as the

wisest. We repeat it. He owed everything to this boldness of determination,

and his most brilliant campaigns would have been exposed to the sam imputations as have attached to the one we have described, if they had not succeeded.

(- p 148)

"In February of 1812, the alliance between France and Prussia against Russia was concluded.

The party in Prussia, which still felt courage to resist, and refused to acknowledge the necessity of a junction with France, might properly be called the Scharnhorst party ...

Scharnhorst quitted the centre of government, and betook himslef to Silesia ... Major von Boyen, his intimate friend, who had held the function of personal communicaation with the King on military affairs, now obtained his conge, carrying with him the rank of colonel and a small donation. It was his intention to go to Russia. Colonel von Gneisenau, lately made state councillor, left the service at the same time, with a like intention. ...

(- p 1)

"In February of 1812, the alliance between France and Prussia against Russia was concluded.

The party in Prussia, which still felt courage to resist, and refused to acknowledge the necessity of a junction with France, might properly be called the Scharnhorst party ...

Scharnhorst quitted the centre of government, and betook himslef to Silesia ... Major von Boyen, his intimate friend, who had held the function of personal communicaation with the King on military affairs, now obtained his conge, carrying with him the rank of colonel and a small donation. It was his intention to go to Russia. Colonel von Gneisenau, lately made state councillor, left the service at the same time, with a like intention. ...

(- p 1)

... he [Phull] had, from the earliest period, led a life so secluded and contemplative, that he knew nothing of the occurances of the daily world; Julius Caesar and Frederick the Great (picture ->) were the heroes and the writers of his predilection. The more recent phenomena of war passed over him without impression.

(- p 3)

... he [Phull] had, from the earliest period, led a life so secluded and contemplative, that he knew nothing of the occurances of the daily world; Julius Caesar and Frederick the Great (picture ->) were the heroes and the writers of his predilection. The more recent phenomena of war passed over him without impression.

(- p 3)

Phull's plan was that the 1st Western Army should withdraw into an entrenched camp, for which he had selected the neighbourhood of the middle Dvina; that the earliest reinforcements should be sent hither, and a great provision of articles of subsistence be accumulated there; and that Bagration with the 2nd Western Army should press forward on the right flank and rear of the enemy, should engage himself in the pursuit of the 1st Western Army. Tormasov was destined to the defence of Volhynia against the Austrians.

Phull's plan was that the 1st Western Army should withdraw into an entrenched camp, for which he had selected the neighbourhood of the middle Dvina; that the earliest reinforcements should be sent hither, and a great provision of articles of subsistence be accumulated there; and that Bagration with the 2nd Western Army should press forward on the right flank and rear of the enemy, should engage himself in the pursuit of the 1st Western Army. Tormasov was destined to the defence of Volhynia against the Austrians.

The Author was several times sent to General Barclay (see picture) to hurry him on his retreat; and, although Colonel Wolzogen was there, and acted the part of mediator, was always ill received. The Russian rearguard had the advantage , in several affairs, with the French advanced troops. This gave the troops and their leaders a certain confidence; and General Barclay, a very calm man, feared to impair this spirit by a retreat without resisting. (- p 16)

The Author was several times sent to General Barclay (see picture) to hurry him on his retreat; and, although Colonel Wolzogen was there, and acted the part of mediator, was always ill received. The Russian rearguard had the advantage , in several affairs, with the French advanced troops. This gave the troops and their leaders a certain confidence; and General Barclay, a very calm man, feared to impair this spirit by a retreat without resisting. (- p 16)

Meanwhile, the events of the war had taken a shape by no means in consonance with the plans of General Phull. When the moment arrived for forwarding to General Bagration (see picture) the order for an offensive movement on the French rear, the Russian courage failed, and either the representations of that general, or the sensation of weakness, brought it to this; that Bagration took a line of retreat, with a view to a later junction with the 1st Western Army, a resolution by which was avoided a leading calamity incident to the plan of Phull, viz. the total destruction of this 2nd Western Army.

Meanwhile, the events of the war had taken a shape by no means in consonance with the plans of General Phull. When the moment arrived for forwarding to General Bagration (see picture) the order for an offensive movement on the French rear, the Russian courage failed, and either the representations of that general, or the sensation of weakness, brought it to this; that Bagration took a line of retreat, with a view to a later junction with the 1st Western Army, a resolution by which was avoided a leading calamity incident to the plan of Phull, viz. the total destruction of this 2nd Western Army.  The Tzar, therefore, saw his plan of campaign, on which he had at first depended, half-destroyed; he saw his army in Drissa about 1/6 weaker than he had expected; he heard from all sides significant expressions of opinion respecting the camp; he had lost his confidence in the plan and its author; he felt the difficulty of commanding such an army.

The Tzar, therefore, saw his plan of campaign, on which he had at first depended, half-destroyed; he saw his army in Drissa about 1/6 weaker than he had expected; he heard from all sides significant expressions of opinion respecting the camp; he had lost his confidence in the plan and its author; he felt the difficulty of commanding such an army.

The march to Witebsk was accomplished in 10 days - no great speed, but the Russians had learnt from their detachments of light cavalry that the French had not yet taken the direction of Witebsk. Barclay, on arriving, marched through the town, and placed himself on the left bank of the Dwina ... A more detestable field of battle could hardly be imagined. General Barclay, on the day following his arrival, had pushed forward General Tolstoi Ostermann (see picture) as an advance guard to Ostrovno. This officer was attacked on the 26th by Murat, and suffered a considerable defeat ...

The march to Witebsk was accomplished in 10 days - no great speed, but the Russians had learnt from their detachments of light cavalry that the French had not yet taken the direction of Witebsk. Barclay, on arriving, marched through the town, and placed himself on the left bank of the Dwina ... A more detestable field of battle could hardly be imagined. General Barclay, on the day following his arrival, had pushed forward General Tolstoi Ostermann (see picture) as an advance guard to Ostrovno. This officer was attacked on the 26th by Murat, and suffered a considerable defeat ...  Davoust ... after making several other detachments he marched with his main body on Mokhilev, which he reached on the 20th July. He had now but 20,000 men remaining, with whom he put himself in motion against Bagration, who hadd 45,000.

He found, about a mile and half from Mohilev, a strong position at the village of Saltanovka, in which he waited for Bagration on the 22nd, and was attacked by him ineffectually on the 23rd.

The latter had not the courage to devote his whole force to this attack, nor time to turn the position. It therefore remained rather a feint on his part with his cavalry and the corps of Rajefskoi while he was throwing a bridge over the river at Staroi-Bychow. He effected his passage the 24th, and retired by Mstislaw upon Smolensk, which he reached on the 4th August, 2 days after Bagration. (- p 32)

Davoust ... after making several other detachments he marched with his main body on Mokhilev, which he reached on the 20th July. He had now but 20,000 men remaining, with whom he put himself in motion against Bagration, who hadd 45,000.

He found, about a mile and half from Mohilev, a strong position at the village of Saltanovka, in which he waited for Bagration on the 22nd, and was attacked by him ineffectually on the 23rd.

The latter had not the courage to devote his whole force to this attack, nor time to turn the position. It therefore remained rather a feint on his part with his cavalry and the corps of Rajefskoi while he was throwing a bridge over the river at Staroi-Bychow. He effected his passage the 24th, and retired by Mstislaw upon Smolensk, which he reached on the 4th August, 2 days after Bagration. (- p 32)

The mass of troops under Jerome (see picture), which was immediately destined against Bagration, and by the 10th July had advanced to Novogrodeck, following Bagration's march to Mir. There Platoff laid an ambuscade for his advance guard, which occasioned it severe loss, and which seems to have made Jerome cautious. He allowed Bagration to delay for 3 days in Njeswisch, and was still there himself on the 16th, when Buonaparte sent him severe remonstrances on his slowness, and ordered him to place himslef under orders of Davoust. Discontented with this, he forthwith left the army. (- p 32)

The mass of troops under Jerome (see picture), which was immediately destined against Bagration, and by the 10th July had advanced to Novogrodeck, following Bagration's march to Mir. There Platoff laid an ambuscade for his advance guard, which occasioned it severe loss, and which seems to have made Jerome cautious. He allowed Bagration to delay for 3 days in Njeswisch, and was still there himself on the 16th, when Buonaparte sent him severe remonstrances on his slowness, and ordered him to place himslef under orders of Davoust. Discontented with this, he forthwith left the army. (- p 32)

Barclay had pushed out a strong rearguard from Witebsk against the French, on the left bank

of the Dwina which ... between Ostrowno and Witebsk, had continual

and lively actions with Murat ...

Barclay had pushed out a strong rearguard from Witebsk against the French, on the left bank

of the Dwina which ... between Ostrowno and Witebsk, had continual

and lively actions with Murat ...

He advanced, therefore .. against Kliastitzi (see picture), and fell upon Oudinot the 31st July with 20,000 men near Jakubowo, and beat him. On the pursuit, however, the following day his advanced guard under General Kulniev, after crossing the Drissa, suffered such a defeat as would have overbalanced the advantage of the day before, if General verdier had not in his turn stumbled on the main body of Wittgenstein, and been compelled to retire with great loss ...

Schwarzenberg was advancing against Tormasow.

He advanced, therefore .. against Kliastitzi (see picture), and fell upon Oudinot the 31st July with 20,000 men near Jakubowo, and beat him. On the pursuit, however, the following day his advanced guard under General Kulniev, after crossing the Drissa, suffered such a defeat as would have overbalanced the advantage of the day before, if General verdier had not in his turn stumbled on the main body of Wittgenstein, and been compelled to retire with great loss ...

Schwarzenberg was advancing against Tormasow.

Barclay, therefore, resolved leaving behind only the division of Neverovski, which had been advanced on Krasnoi, to direct both armies on Rudnia, as the central point of the enemy's position ... The result of this unsuspected movement was that Platoff fell, with the Russian advanced guard, on that of the French under Sebastiani (see picture) at Inkovo, and drove it in with great loss.

Barclay, therefore, resolved leaving behind only the division of Neverovski, which had been advanced on Krasnoi, to direct both armies on Rudnia, as the central point of the enemy's position ... The result of this unsuspected movement was that Platoff fell, with the Russian advanced guard, on that of the French under Sebastiani (see picture) at Inkovo, and drove it in with great loss.

On the 16th the French attacked Smolensk (see picture) ... In the night og the 18th the Russians abandoned Smolensk but remained on the right bank of the Dnieper, opposite the place, and prevented the passage of the French. In the night of the 19th Barclay began his retreat with the 1st Western Army ... This gave occasion to the affair of the rearguard at Valutina Gora, in which about 1/3 of the respective armies were engaged. The strength of the Russian position, which lay behind marshy hollows, enabled them to maintain the field of battle till dark, and to secure their retreat. (- p 37)

On the 16th the French attacked Smolensk (see picture) ... In the night og the 18th the Russians abandoned Smolensk but remained on the right bank of the Dnieper, opposite the place, and prevented the passage of the French. In the night of the 19th Barclay began his retreat with the 1st Western Army ... This gave occasion to the affair of the rearguard at Valutina Gora, in which about 1/3 of the respective armies were engaged. The strength of the Russian position, which lay behind marshy hollows, enabled them to maintain the field of battle till dark, and to secure their retreat. (- p 37)

On the 29th Kutuzov arrived, and received the command from Barclay, who remained at the head of the 1st Western Army. ... (- p 38)

On the 29th Kutuzov arrived, and received the command from Barclay, who remained at the head of the 1st Western Army. ... (- p 38)

It was thus that Colonel Toll could find no better position than that of Borodino, which is however a deceptive one, for it promises at first sight more than it performs ...

It was thus that Colonel Toll could find no better position than that of Borodino, which is however a deceptive one, for it promises at first sight more than it performs ...

The works [redoubts], which had been thrown up, lay partly on the left wing, partly before the centre, and one of them as an advanced post, a couple of thousand paces before the left wing. These works were only ordered at the moment when the army arrived in position. They were in a sandy soil, open behind, destitute of all external devices, and could therefore only be considered as individual features in a scheme for increasing the defensive capabilities of the position. None of them could hold out against a serious assault, and in fact most of them were lost and regained 2 or 3 times. It must, however, be said of them that they contributed their share to the substantial and hearty resistance of the Russians; they formed for the left wing the only local advantage which remained to the Russians in that quarter. (- p 88)

The works [redoubts], which had been thrown up, lay partly on the left wing, partly before the centre, and one of them as an advanced post, a couple of thousand paces before the left wing. These works were only ordered at the moment when the army arrived in position. They were in a sandy soil, open behind, destitute of all external devices, and could therefore only be considered as individual features in a scheme for increasing the defensive capabilities of the position. None of them could hold out against a serious assault, and in fact most of them were lost and regained 2 or 3 times. It must, however, be said of them that they contributed their share to the substantial and hearty resistance of the Russians; they formed for the left wing the only local advantage which remained to the Russians in that quarter. (- p 88)

The direction of Kutusov's retreat from Mozhaisk to Moscow has been made matter of censure. He might, it has been said, have pursued the road by Wereja to Tula. On this road, however, he would not have found a morsel of bread. Everything which an army should have in its rear, every element of its life was on the Moscow Road.

The direction of Kutusov's retreat from Mozhaisk to Moscow has been made matter of censure. He might, it has been said, have pursued the road by Wereja to Tula. On this road, however, he would not have found a morsel of bread. Everything which an army should have in its rear, every element of its life was on the Moscow Road.  We have here one or two general observations to make on the Russian retreat and French

pursuit, which may contribute to the better understanding of the result of the campaign.

The Russians found from Witebsk to Moscow in all the chief provincial towns magazines of flour,

grits, biscuit, and meat; in addition to these, enormous caravans arrived from the interior

with provisions, shoes, leather, and other necessaries. They had also at their command a mass

of cariages, the teams of which were subsisted without difficulty since corn and oats were

on the ground, and the caravans of the country are accustomed, even in time of peace, to

pasture their draft cattle in the meadows. This put the Russians in condition everywhere to

encamp

We have here one or two general observations to make on the Russian retreat and French

pursuit, which may contribute to the better understanding of the result of the campaign.

The Russians found from Witebsk to Moscow in all the chief provincial towns magazines of flour,

grits, biscuit, and meat; in addition to these, enormous caravans arrived from the interior

with provisions, shoes, leather, and other necessaries. They had also at their command a mass

of cariages, the teams of which were subsisted without difficulty since corn and oats were

on the ground, and the caravans of the country are accustomed, even in time of peace, to

pasture their draft cattle in the meadows. This put the Russians in condition everywhere to

encamp

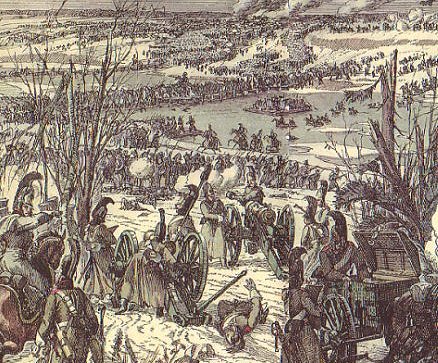

On this march we saw Moscow burning without interruption, and although we were 7 miles distant, the wind sometimes blew the ashes upon us. (- p 108)

On this march we saw Moscow burning without interruption, and although we were 7 miles distant, the wind sometimes blew the ashes upon us. (- p 108)

to the last moment he led the world to believe that he would venture on a second battle for the salvation of Moscow. ... In any case it is one of the most remarkable phenomena in history that an action which in public opinion had so vast influence on the fate of Russia should stand out like the offspring of an illegitimate amour, without a father to acknowledge it, and to all appearance should be destined to remain wrapt in eternal mystery.

to the last moment he led the world to believe that he would venture on a second battle for the salvation of Moscow. ... In any case it is one of the most remarkable phenomena in history that an action which in public opinion had so vast influence on the fate of Russia should stand out like the offspring of an illegitimate amour, without a father to acknowledge it, and to all appearance should be destined to remain wrapt in eternal mystery.

The flanking position of Kutusov had also the afvantage of more easily operating on the enemy's line of retreat, and thus contributed something to the result, only it cannot at all be considered as the main cause of that result. ... That Colonel Toll, before reaching Moscow, wished to bend off towards Kaluga was in fact, only with the idea of not exposing Moscow to danger for, otherwise, the deflection was easier to execute at Moscow than anywhere else. ...

The flanking position of Kutusov had also the afvantage of more easily operating on the enemy's line of retreat, and thus contributed something to the result, only it cannot at all be considered as the main cause of that result. ... That Colonel Toll, before reaching Moscow, wished to bend off towards Kaluga was in fact, only with the idea of not exposing Moscow to danger for, otherwise, the deflection was easier to execute at Moscow than anywhere else. ...

The march of Buonaparte on Kaluga was a very necessary beginning of his retreat, without the intermixture of the notion of another road, Kutuzov, from Tarutino,

had 3 marches less to Smolensk than Buonaparte from Moscow; the latter, therefore, was compelled to begin, by endeavouring to overwhelm the other, and gain the advance of him before he began his real retreat. It would naturally have been more advantageouos to him if he could have manoeuvered Kutusov

back to Kaluga. He hoped to effect this by suddenly passing from the old road to the new, whereby he menaced Kutusov's left flank.

The march of Buonaparte on Kaluga was a very necessary beginning of his retreat, without the intermixture of the notion of another road, Kutuzov, from Tarutino,

had 3 marches less to Smolensk than Buonaparte from Moscow; the latter, therefore, was compelled to begin, by endeavouring to overwhelm the other, and gain the advance of him before he began his real retreat. It would naturally have been more advantageouos to him if he could have manoeuvered Kutusov

back to Kaluga. He hoped to effect this by suddenly passing from the old road to the new, whereby he menaced Kutusov's left flank.

As this however and the attempt at Malo-Yaroslavetz (see picture --> ) appeared failures, he made the best of it; to leave some 20,000 on the field of a general action, in order to end by retiring after all.

(- p 115)

As this however and the attempt at Malo-Yaroslavetz (see picture --> ) appeared failures, he made the best of it; to leave some 20,000 on the field of a general action, in order to end by retiring after all.

(- p 115)

As no proposals for peace came from Petersburg (and already a forthnight had been wasted in inactivity)

Buonaparte determined to make the first advance, and on the 4th October sent Lauriston to Kutusov with a letter for the Tzar Alexander.

Kutusov received the letter, but not the bearer. Buonaparte suffered 10 days more to elapse, and then renewed the attempt, beginning at the time

to think on his retreat. Kutusov received Lauriston this time, which produced some specious negotiations, by which

Buonaparte was misled to postpone his retreat for some days longer.

As no proposals for peace came from Petersburg (and already a forthnight had been wasted in inactivity)

Buonaparte determined to make the first advance, and on the 4th October sent Lauriston to Kutusov with a letter for the Tzar Alexander.

Kutusov received the letter, but not the bearer. Buonaparte suffered 10 days more to elapse, and then renewed the attempt, beginning at the time

to think on his retreat. Kutusov received Lauriston this time, which produced some specious negotiations, by which

Buonaparte was misled to postpone his retreat for some days longer.

Marshal Victor's II Army Corps joined St.Cyr's IX Army Corps on 28 October and together moved on Beszenkovichi.

Wittgenstein left Polotzk area and moved against Victor who wished to conceal the junction of II and IX

Army Corps. On 1 November Victor and one of St.Cyr's divisions merged.

Wittgenstein attacked them at Czaszniki and then at Smoliany. The French and Baden troops fought well and

withdrew in good order. Witgenstein established bridgehead at Smoliany and waited for the arrival of Admiral Chichagov's army.

Victor and St.Cyr completed their merger and moved on Torbinka, Chereia and Lukonil.

Marshal Victor's II Army Corps joined St.Cyr's IX Army Corps on 28 October and together moved on Beszenkovichi.

Wittgenstein left Polotzk area and moved against Victor who wished to conceal the junction of II and IX

Army Corps. On 1 November Victor and one of St.Cyr's divisions merged.

Wittgenstein attacked them at Czaszniki and then at Smoliany. The French and Baden troops fought well and

withdrew in good order. Witgenstein established bridgehead at Smoliany and waited for the arrival of Admiral Chichagov's army.

Victor and St.Cyr completed their merger and moved on Torbinka, Chereia and Lukonil.

From General Diebitsch [or Dybicz, see picture] we had expected a bold and self-forgetting rush forward. How far he advocated such, and failed, we could

not learn, but it was easy to observe that unity did not prevail at headuarters [of Wittgenstein's army] at this crisis.

From General Diebitsch [or Dybicz, see picture] we had expected a bold and self-forgetting rush forward. How far he advocated such, and failed, we could

not learn, but it was easy to observe that unity did not prevail at headuarters [of Wittgenstein's army] at this crisis.

Wittgenstein [see picture --> ] made some 10,000 prisoners on these 2 days, and among them an entire division. With

this brilliant result he soothed his conscience, and transferred the blame on Chichagov, who had abandoned the ground as far as Zembin

at an unlucky moment. The latter general seems certainly to have exhibited no great capacity for command in this campaign.

It is however true, that every man was possessed with the idea that the enemy would take the direction

of Bobruisk. Even from Kutusov advices were forwarded to this effect.

Wittgenstein [see picture --> ] made some 10,000 prisoners on these 2 days, and among them an entire division. With

this brilliant result he soothed his conscience, and transferred the blame on Chichagov, who had abandoned the ground as far as Zembin

at an unlucky moment. The latter general seems certainly to have exhibited no great capacity for command in this campaign.

It is however true, that every man was possessed with the idea that the enemy would take the direction

of Bobruisk. Even from Kutusov advices were forwarded to this effect.

From the Beresina Chichagov took the lead in the pursuit, followed by Miloradovich.

Platoff (-->) and several other Cossack

corps hung on the French flanks, or even gained their front.

(- p 124)

From the Beresina Chichagov took the lead in the pursuit, followed by Miloradovich.

Platoff (-->) and several other Cossack

corps hung on the French flanks, or even gained their front.

(- p 124)

The Russian army might be beaten, scattered. Moscow might be conquered in one campaign, but we are of opinion that

one essential condition was wanting in Buonaparte's execution of the plan - this was to remain formidable after the

acquisition of Moscow. We believe that this was neglected by Buonaparte only in consequence

of his characteristic negligence in such matters. He reached Moscow with 90,000 men; he should have reached

it with 200,000. This would have been possible if he had handled his army with more care and forbearance.

(- p 145)

The Russian army might be beaten, scattered. Moscow might be conquered in one campaign, but we are of opinion that

one essential condition was wanting in Buonaparte's execution of the plan - this was to remain formidable after the

acquisition of Moscow. We believe that this was neglected by Buonaparte only in consequence

of his characteristic negligence in such matters. He reached Moscow with 90,000 men; he should have reached

it with 200,000. This would have been possible if he had handled his army with more care and forbearance.

(- p 145)

The famous conqueror in question was so far from deficient in this quality that he would have chosen the

most audacious course from inclination, even if his genius had not suggested it to him as the

wisest. We repeat it. He owed everything to this boldness of determination,

and his most brilliant campaigns would have been exposed to the sam imputations as have attached to the one we have described, if they had not succeeded.

(- p 148)

The famous conqueror in question was so far from deficient in this quality that he would have chosen the

most audacious course from inclination, even if his genius had not suggested it to him as the

wisest. We repeat it. He owed everything to this boldness of determination,

and his most brilliant campaigns would have been exposed to the sam imputations as have attached to the one we have described, if they had not succeeded.

(- p 148)