|

.

"Most sources state as a bald fact that 5.000 Frenchmen fell dead or wounded

at Hougoumont but without justifying this number and not taking into account

the heavy losses suffered during the retreat after battle."

- Mark Adkin

|

Beginning of the battle and the attack on Hougoumont.

The French troops arrived slowly on the battlefield

and acclaimed the Emperor as they took up their positions.

The British, Germans and Netherland troops could hear

the French regimental bands playing.

Between 7 AM and 8:30 AM Wellington inspected the line from west to east, this included visiting Hougoumont

and ordering reinforcements. (At 10 AM he visited Hougoumont the second time.)

At 9 AM Reille's II Army Corps passed in front of Le Caillou, followed by the Imperial Guard, and Kellermann's

Cavalry Corps. Then came a single division (Durutte's) of d'Erlon's I Army Corps.

The waterlogged state of the ground was hindering the movements of the cannons and howitzers.

Napoleon mounted his mare La Marie and went ahead of the troops, stopping beyond Rossomme farm.

The French troops arrived slowly on the battlefield and acclaimed the Emperor as they took up their positions.

The British, Germans and Netherland troops could hear the French regimental bands playing.

Napoleon had ordered his troops to be in position at 9 AM, however, this was not to be.

The supply trains only caught up with their troops late the previous night or early in the morning, adding to the delays.

The soldiers had to search for something edible, causing the units further dispersed.

According to Peter Hofschroer, at 9 AM Reille's II Corps reached the battlefield,

a long way behind was the Imperial Guard, the cavalry, and Lobau's VI Corps.

Durutte's division of de Erlon's I Corps reached the battlefield about midday.

The delays were making up, in part, for the time Blucher's troops were losing on the muddy roads

between Wavre and Lasne.

Hougoumont and its defenders.

According to Mark Adkin the myth that Hougoumont was defended solely

by the British Guards has arisen, not so much with serious students

of the battle, but through the casual reader or visitor to the battlefield.

Great emphasis is placed in many accounts of the fight on the role played by the Guards.

This misunderstanding is certainly compounded, if not caused,

by the numerous plaques commemorating the actions of the Guards in Hougoumont.

Five plaques are dedicated to the Guards and two to the French.

There is nothing to show others played an important role.

Photo: wargamer's model of Hougoumont in 1815. Although NOT accurate in every detail,

it gives a good impression of what it looked like. Mark Adkin - "Waterloo Companion."

Photo: wargamer's model of Hougoumont in 1815. Although NOT accurate in every detail,

it gives a good impression of what it looked like. Mark Adkin - "Waterloo Companion."

Hougoumont, originally called Gomont or Goumont, was a Chateau and farm lying about 5 km

south of the village of Waterloo. At the time of the Battle of Waterloo, the Chateau was

owned by the Chevalier de Louville. He lived in Nivelles and rent the

Chateau to a farmer called Dumonceau. The Chateau building itself, however, remained unnoccupied.

Hougoumont was a robust compound surrounded by walls, with stables, barns, and houses.

There was a massive gate on the south side, leading to an inner courtyard.

Hougoumont was a robust compound surrounded by walls, with stables, barns, and houses.

There was a massive gate on the south side, leading to an inner courtyard.

The compound itself faced the Allies. There was a garden, whose walls extended eastward for

approx. 200 yards, and beyond it was an orchard. It all, however, was known only to the

Allied troops who were occupying the farm, all the French could see from their positions were

trees and few buildings.

At about 09.30 AM the 1st Battalion of Nassau was brought to Hougoumont.

Its carabineer company took up positions inside the buildings to the south.

The voltigeur company lined up with a Brunswick jäger company at the edge of the wood.

The garden walls were defended by two companies, and the hedge of the orchard by one company.

One company was held in reserve in the wood.

General von Kruse writes: "About 9:30 AM ... the 1st Battalion of the regiment, received the

order to occupy the farm of Hougoumont that lay ahead of the centre of the right flank.

A company of Brunswick jager stood along the fence of the wood near the farm and, behind

the gardens, a battalion of the 2nd English Guard

Regiment."

General von Kruse writes: "About 9:30 AM ... the 1st Battalion of the regiment, received the

order to occupy the farm of Hougoumont that lay ahead of the centre of the right flank.

A company of Brunswick jager stood along the fence of the wood near the farm and, behind

the gardens, a battalion of the 2nd English Guard

Regiment."

The I Battalion of 2nd Nassau Regiment (I/2 Nassau) was commanded by Major Busgen.

This is what he has to say: "The farm was in the shape of a long, closed rectangle. ...

On my arrival with the battalion, the farm and the garden were unoccupied.

A company of Brunswick Jagers stood on the furthest edge of the wood.

A battalion [sic] of English Guards ... was deployed partly behind the farm,

and partly in a sunken road behind the gardens mentioned ... From the measures of

defence already undertaken, it was clear that this position was already occupied.

One room house, as was later apparent, contained supplies

of infantry ammunition. I immediately undertook the necessary deployment for the defence.

I had the Grenadier Company occupy the buildings, and sent two companies to the vegetable

garden next to them. I placed one company behind the hedge of the orchard, moved the

voltigeurs into line with the Brunswick Jagers, and placed one company in reserve a little

to the rear. Hardly was this deployment finished when the enemy

began their attack on the wood with a heavy bombardement of shell and canister."

According to British researcher Mark Adkin the myth that Hougoumont was defended solely

by the British Guards has arisen, not so much with serious students of the battle, but

through the more casual reader or visitor to the battlefield.

Great emphasis is placed in many accounts of the fight on the role played by the Guards.

This misunderstanding is certainly compounded, if not caused, by the numerous plaques

commemorating the actions of the Guards in Hougoumont. Five plaques are dedicated to the

Guards and two to the French.

There is nothing to show others played an important role.

| Troops in Hougoumont |

Strength |

11:30 AM

detachment (10-20 men) of Netherland light infantry

I am not sure if they were withdrawn before the battle or not.

grenadier company (135 men) of I/2nd Nassau in the buildings

two companies (2 x 135 men) of I/2nd Nassau in the Garden

one company (135 men) of I/2nd Nassau in Great Orchard

two companies (2 x 135 men) of I/2nd Nassau in the Wood

one company (100 men) of Field Jager Corps

detachment (50 men) of Luneburg Light Battalion

detachment (50 men) of Grubenhagen Light Battalion

light company (100 men) of II/2nd British Guards in the Garden

light company (100 men) of II/3rd British Guards west of the buildings |

Total 1.210 men

Dutch and Belgians (10-20) Dutch and Belgians (10-20)

Germans (1,000) Germans (1,000)

British (200) British (200)

These forces were attacked by half of

French 6th Division under Prince Jérôme

(1st and 2nd Light Infantry Regiment)

|

12.30 - 1.15 PM

I/2nd Nassau (800 men)

seven companies of II/2nd British Guards (7 x 100 men)

four light companies of British Guards (4 x 100 men)

|

Total 1.900 men

Germans (1,500) Germans (1,500)

British (400) British (400)

These forces were attacked by the entire

French 6th Division under Prince Jérôme

|

2.45 - 7.00 PM

II/2nd British Guard (900 men)

II/3rd Guard British (900 men)

I/2nd Nassau (800 men)

|

Total 2.600 men

Germans (800) Germans (800)

British (1,800) British (1,800)

These forces were attacked by French

6th Division under Prince Jérôme and

9th Division under Maximilien Foy

|

7.00 - 8.00 PM

II/2nd British Guard (900 men)

II/3rd Guard British (900 men)

I/2nd Nassau (800 men)

II KGL Line Battalion (520 men)

Hannoverian Saltzgitter Landwehr Battalion (640 men)

Brunswick Advance Guard Battalion (650 men)

Brunswick Leib Battalion (565 men)

Brunswick I Light Battalion (680 men)

|

Total 5.655 men

Germans (3,855) Germans (3,855)

British (1,800) British (1,800)

These forces were attacked by French

6th Division under Prince Jérôme and

9th Division under Maximilien Foy

|

Actually Wellington garrisoned all three farms, Hougoumont, La Haye Sainte and Papelotte.

Most of the defenders were German troops:

in La Haye Sainte 400-500 Germans

in Papelotte 900 Germans

in Hougoumont 2.000-5,600 Germans and British

.

The first French attacks on Hougoumont.

"The murderous fire coming from the buildings, the garden wall

and orchard hedge halted the French."

- Major Busgen of the Nassauers

Artillery of Reille's II Army Corps opened fire and the Allied batteries immediately responded.

Captain Sandham's Battery claims to have fired the first Allies cannon shot

of the battle - a claim disputed by Cleeve's Battery of King's German Legion.

At about midday, GdD Reille decided to send light infantry into the Hougoumont wood

and see what would happen. To begin the attack Reille selected Jerome's Bonaparte's division.

Artillery of Reille's II Army Corps opened fire and the Allied batteries immediately responded.

Captain Sandham's Battery claims to have fired the first Allies cannon shot

of the battle - a claim disputed by Cleeve's Battery of King's German Legion.

At about midday, GdD Reille decided to send light infantry into the Hougoumont wood

and see what would happen. To begin the attack Reille selected Jerome's Bonaparte's division.

Jerome did not owe his command to any particular military ability; in fact,

his performance as commander of the Westphalian troops during Napoleon's invasion of Russia

had been a failure. Within the army, Jerome was better known for his

scandalous American wife, whom Napoleon had refused to allow into France.

Jerome did not owe his command to any particular military ability; in fact,

his performance as commander of the Westphalian troops during Napoleon's invasion of Russia

had been a failure. Within the army, Jerome was better known for his

scandalous American wife, whom Napoleon had refused to allow into France.

Jerome ordered the 1st Light to attack the wood. (Two days earlier the 1st Light

formed in squares had thrown back Wellington's cavalry at Quatre Bras.)

The light infantrymen had barely taken up their positions before Hougoumont when the order came to advance into the wood. They immediately

formed themselves in three columns and moved forward screened by skirmishers. The French skirmishers

were running toward the trees, leaping a ditch, and getting through the hedge.

They found themselves under lively fusillades from the German light infantry.

The columns of the 1st Light were hit and their officers ordered them down into a little

lane-sunken that ran right along their front. The French officers started sending small

troops into the wood, where the skirmishers exchanged shots with the enemy. "At that moment there were about a thousand muskets at

Hougoumont, of which perhaps half were defending the perimeter of the park." (- A. Barbero)

The columns of the 1st Light were hit and their officers ordered them down into a little

lane-sunken that ran right along their front. The French officers started sending small

troops into the wood, where the skirmishers exchanged shots with the enemy. "At that moment there were about a thousand muskets at

Hougoumont, of which perhaps half were defending the perimeter of the park." (- A. Barbero)

At 11 am Petters' Netherlands battery received order to move forward and take position on the plateau of Mont St.Jean.

Petter wrote that his guns were "... standing opposite the farm named Hougoumont.... in front of us was the farm ...

" (Erwin Muilwijk wrote that "In a recent book by Mark Adkin "Waterloo Companion", the battery is left standing in

reserve for the entire battle, see map 16, page 274.")

Petters' battery and British battery under Ramsay supported the defenders of Hougoumont.

As soon as Petters' battery deployed the French fired on them and hit several caissons that exploded into the air.

But they held their ground and remained firing until 7 o'clock in the evening before received order to pull back from the

artillery line. They lost many train horses and the battery was almost unteamed.

Jerome sent another regiment into the wood. The two units were under GdB Bauduin who was on

horseback and urging his men forward. The Germans fired well-aimed shots and Bauduin fell from his horse.

He was killed almost at once. The Germans became frustrated by the rapidly growing number of French infantrymen

pouring into the wood. They ran short of ammunition and fell back to the buildings and the garden.

Major Busgen of the I/2nd Nassau writes: "Under close pursuit from the French, the retiring troops

fell back partly around the right of the buildings, partly to the left

between the garden wall and the orchard hedge."

The French reached the 6-feet high wall protecting the garden. But the Germans were waiting

for them, and together with the light companies of the British Foot Guards they repulsed the attackers.

"The murderous fire coming from the buildings, the garden wall and orchard hedge halted the French."

(- Major Busgen of the Nassauers)

The French skirmishers fell back into the safety of the wood, where also stood their columns.

Howitzer battery under Mjr. Bull (one of the few officers who wore a beard) opened fire

and shells began to explode among the trees and above the heads of the French.

The French abandoned the wood and the hedgerows at once. The Germans and the Foot Guards

went forward and retook the lost ground.

Artillery duel.

During the cannonade the French, German and British infantry

remained stretched out on the ground in hollows and sunken lanes

The French south of Hougoumont, while the Allies north.

Reille's artillery kept firing on all cylinders and several guns had been brought up

as far as the Nivelles Road. Almost all the British eyewitness accounts confirm that the

British and German infantry massed on the high ground beyond Hougoumont came under fire and

suffered a steady attrition that gradually began to wear on the men's nerves.

Reille's artillery kept firing on all cylinders and several guns had been brought up

as far as the Nivelles Road. Almost all the British eyewitness accounts confirm that the

British and German infantry massed on the high ground beyond Hougoumont came under fire and

suffered a steady attrition that gradually began to wear on the men's nerves.

Most of the British battalions were formed in column of companies (not a thin red line).

It was a very deep formation with all 10 companies lined up one behind the other.

It was easy to maneuver battalions so deployed and therefore ideal formation for waiting troops;

but it certainly wasn't suitable for withstanding artillery bombardement. The cavalry also suffered from atyillery fire.

Sergeant Wheeler of the British 51st Light writes: "A shell now fell into the column

of the 15th Hussars and bursted. I saw a sword and scabbard fly out from the column ... grape and shells were dupping about like hell,

this was devilish annoying. As we could not see the enemy, although they

were giving us a pretty good sprinkling of musketry ..."

A British officer wrote that one of the French batteries "was committing great devastation amongst our troops in and near Hougoumont."

Bull's howitzer battery also got under fire, suffered losses in men, wagons and horses, and exhausted their own ammunition

to such a point that, no more than 2 hours after the beginning of the battle, they were

compelled to abandon the line of fire.

The fire of the French artillery also distracted the British gunners. Instead of targeting

the French columns they got involved in counter-battery fire. Wellington had expressely

forbade it but it was ignored. (Napoleon explained: "When gunners are under attack from an enemy battery, they can never be made to fire on massed

infantry. It's natural cowardice, the violent instinct of self-preservation ...")

During the artillery duel part of Reille's infantry remained stretched out on the ground

in hollows and sunken lanes. The British and German infantry were also stretched out on the

ground, beyond Hougoumont.

The gates of chateau.

"The English barricaded themselves there;

the French made their way in,

but could not stand their ground. "

- Victor Hugo

While Bauduin's two units stayed in the shelter of a sunken lane, Jerome sent forward two other regiments

of his division. The freshmen were led by GdB Soye and they compelled the Germans

and Brits to retreat to the buildings and the garden. "Towards one o'clock, the French renewed their attack,

moving against the buildings and gardens in a great rush, attempting to climb the garden wall and to seize the

orchard hedge. However, the skirmish fire from the garden wall chased them off and they were repelled at all points.

In this attack, the enemy set lights to several stacks of hay and straw close to the farm, intending to set the

buildings alight, but this was not successful." (- Mjr. Busgen)

The French began maneuvering around the flanks. Several columns moved across the plain

west of Hougoumont. They were under cover from horse battery that had advanced beyond ythe Nivelles Road.

Soye's men invaded the orchard, forcing the Germans and British Foot Guards to abandon it.

The guardsmen were chased back into the hollow way (bordered with thorny hedgerows)

that ran in front of the chateau.

The French began maneuvering around the flanks. Several columns moved across the plain

west of Hougoumont. They were under cover from horse battery that had advanced beyond ythe Nivelles Road.

Soye's men invaded the orchard, forcing the Germans and British Foot Guards to abandon it.

The guardsmen were chased back into the hollow way (bordered with thorny hedgerows)

that ran in front of the chateau.

The British and German infantrymen hidden behind garden walls opened fire.

The French stood their ground and engaged the defenders in an intense firefight.

The French hauled a cannon into the orchard.

The guardsmen attempted to capture it but failed miserably. The musketry however was so

fierce that the gunners withdrew the cannon to a more covered position.

Despite being more exposed the French stubbornly held their ground and the exchange of musketry went on,

more or less inconlusively. Meanwhile the Guards had brought an ammunition cart through the

north gate (it was not barricaded).

Bauduin's two regiments moved on the west side of Hougoumont. (After Bauduin's death Col. de

Cubieres had taken command of the brigade.) Pressed by French skirmishers the British light troops were obliged to give ground.

Bauduin's men descended into a sunken lane, and found themselves in front of the north gate.

Col. de Cubieres was mounted and urging his skirmishers forward. His one arm was in a sling

because of a wound he had suffered at Quatre Bras. Within a moment he was wounded again.

Major Ramsay of Royal Horse Artillery was lost to a musket ball early on.

Surprised by the appearance of Cubieres and his skirmishers the Foot Guards beat a hasty retreat, passing through the still-open gate into the farmyard

and closed the big door as fast as they could. Lieutenant Legros - nicknamed "The Smasher"

- took a sapper's axe and positioned himself before the gate.

He choped a hole through the door panel with an axe. Then the barrier yielded to the pressure of many

bodies, and a group of Frenchmen burst inside.

Surprised by the appearance of Cubieres and his skirmishers the Foot Guards beat a hasty retreat, passing through the still-open gate into the farmyard

and closed the big door as fast as they could. Lieutenant Legros - nicknamed "The Smasher"

- took a sapper's axe and positioned himself before the gate.

He choped a hole through the door panel with an axe. Then the barrier yielded to the pressure of many

bodies, and a group of Frenchmen burst inside.

At the beginning of the savage melee that followed, the

panicked Germans and Brits sought refuge in the buildings, leaving Legros' band masters of the field.

A Frenchman armed with an ax chased a German officer, caught up with him at the door, and chopped off one of his hands.

Meanwhile some guardsmen managed to close the gate.

The French found themselves in a crossfire and were killed except a boy-drummer.

Henri Lachouque writes: "In Hougoumont, the show of power developed

into a battle. Jerome persisted; the soldiers would stop at nothing less than a struggle

to death. Soye's brigade, called up in support, penetrated the woods; the battalion of the

1st Brigade - decimated by the Coldstream Guards taking cover behind the orchard walls -

encircled the farm and the chateau in the west, and the 1st Light broke down the north

gateway. There was slaughter in the courtyard, in the corridors of the chateau and in the

chapel. The thatched buildings were set on fire; Jerome was wounded."

Some French infantrymen attempted to climb over the walls but were

shot by the defenders.

Large group of French skirmishers climbed the slope in the direction of the British batteries,

concealing themselves amid the tall crops. In the course of few minutes many gunners and horses were hit

and the battery was forced to abandon the line of fire.

Large group of French skirmishers climbed the slope in the direction of the British batteries,

concealing themselves amid the tall crops. In the course of few minutes many gunners and horses were hit

and the battery was forced to abandon the line of fire.

Wellington decided to alleviate the pressure on the defenders of Hougoumont, two battalions went down the slope in companies, one after the other,

and attacked the enemy. The French surprised by the arrival of so numerous reinforcements

withdrew and abandoned the orchard. Only a handful of men of the 1st Light,

resisted the British and Germans to the last man.

French howitzers set the buildings alight.

"Between 2 and 3 PM, a [French] battery drew up on the right side

of the buildings and began to bombard them heavily with cannons and howitzers.

It did not take long to set them all alight." - Major Busgen, Nassau Battalion

.

"At Hougoumont, the struggle continued unabated. The British Guards light companies,

the Brunswickers and one of du Plat's KGL battalions fought with two

of Foy's regiments. ... A battery of French howitzers lobbed shells into the buildings, setting them alight.

The chateau, the farmhouse, the stables and storehaouses all went up in flames.

The British fell back into the chapel and the gardener's house from where they continued to

fire on the French..." (Hofschroer - "1815 Waterloo Campaign - The German Victory" p 81)

"Between 2 and 3 PM, a [French] battery drew up on the right side of the buildings and began

to bombard them heavily with cannons and howitzers. It did not take long to set them all alight."

(- Major Busgen, Nassau Battalion)

"Between 2 and 3 PM, a [French] battery drew up on the right side of the buildings and began

to bombard them heavily with cannons and howitzers. It did not take long to set them all alight."

(- Major Busgen, Nassau Battalion)

The French grenadier companies led the assault, and they forced their way through a small

side door into the upper courtyard. They even took several prisoners before the

musket fire from the windows and walls drove them out.

The Nassau battalion and British Guards battalion followed them and regained much of the

lost ground. It was the last serious attack on Hougoumont.

The skirmish fire and artillery bombardement

continued to the last minutes of the battle.

"Clearly, the disproportion of the forces involved in the struggle

for Hougoumont is nothing but a legend of historiography.

In the course of the day, the French employed ... 33 battalions

and some 14,000 muskets. Against them, Wellington committed ...

21 battalions - 6 British and 15 German - and a total of 12,000 muskets."

- Alessandro Barbero

The heavy skirmish fire and artillery bombardement continued to the last minutes of the battle

of Waterloo. For all its ferocity the fighting for Hougoumont was a subsidiary part of the day's events.

The heavy skirmish fire and artillery bombardement continued to the last minutes of the battle

of Waterloo. For all its ferocity the fighting for Hougoumont was a subsidiary part of the day's events.

Several sources claim that by the end of the day the entire French II Corps had been sucked

into the struggle for Hougoumont - some 18,000 infantrymen. This is difficult to justify.

The figure hinges on whether Bachelu's division was drawn in. It is clear that at least

his leading brigade attempted to advance on Hougoumont from the south-east around

mid-afternoon. These battalions had to advance 1000 m diagonally across the Allied front.

They came under heavy artillery fire and the attack broke up without reaching H.

For these reason this division has not been included in the number of French troops that

actually assaulted Hougoumont.

The French probably emplyed 5 bateries (34 guns) against Hougoumont. The Duke brought

up to 9 batteries (48-54 guns) into action already within the first hour.

Most sources state as a bald fact that 5.000 Frenchmen fell dead or wounded at Hougoumont

but without justifying this number and not taking into account the heavy losses suffered

during the retreat after battle.

"Historians have often stated, that the French attack against Hougoumont was a gigantic waste,

in which a small number of defenders kept engaged and eventually defeated an immensely superior enemy host.

However, from Napoleon's point of view, the offensive against the perimeter wall of the chateau represented only one aspect of a much broader maneuver, whose objective

was to drive in Wellington's entire right wing, and the duke, knowing what was at stake, responded in kind.

While the Hougoumont defenders never had, at any given moment, more than 2,000 muskets within the perimeter of the chateau, the total number of soldiers in all the battalions that were committed to this section was much higher.

... Reille's corps exerted pressure not only on the troops inside the perimeter of the chateau

but also on all the Allied infantry deployed in that sector, keeping them constantly engaged

until the very last phase of the battle.

Clearly, the disproportion of the forces involved in the struggle for Hougoumont is nothing

but a legend of historiography. In the course of the day, the French employed the three divisions of II Corps in this sector,

for a total of 33 battalions and some 14,000 muskets. Against them, Wellington committed the brigades of Byng, du Plat, Adam,

and Hew Halkett, 5 Brunswick battalions, one from Nassau, .... amounting to 21 battalions

- 6 British and 15 German - and a total of 12,000 muskets."

(- Alessandro Barbero)

|

On May 3rd took place a solemn entry of King Louis XVIII in Paris.

He suffered from gout and

On May 3rd took place a solemn entry of King Louis XVIII in Paris.

He suffered from gout and  Napoleon and his small corps (Elba Battalion, Elba Squadron, and small Corsican battalion

called "Elba Flanquers") returned to France. Napoleon's landed at Antibes,

at 5 PM on 1 March. (See picture).

Napoleon and his small corps (Elba Battalion, Elba Squadron, and small Corsican battalion

called "Elba Flanquers") returned to France. Napoleon's landed at Antibes,

at 5 PM on 1 March. (See picture).

Marshal Ney was on his estate at Coudreaux, more and more convinced it's time for

him to retire. He declared "The Emperor can't come back ! He has abdicated. And if he

were to land, it'd be every Frenchman's duty to fight him."

Marshal Ney was on his estate at Coudreaux, more and more convinced it's time for

him to retire. He declared "The Emperor can't come back ! He has abdicated. And if he

were to land, it'd be every Frenchman's duty to fight him."

Because the British Cabinet had refused to declare war against France as opposed to war against Napoleon,

Wellington was constrained from sending his cavalry across the border. Merlen's Dutch/Belgian cavalry had captured several

French patrols, but were ordered by Wellington to escort them back across the frontier. This situation continued until 13th

June. Frustrated Prince of Orange wrote to Wellington: "I'm going to send back the French prisoners this morning with a

letter to General Count d'Erlon according to your wishes."

Because the British Cabinet had refused to declare war against France as opposed to war against Napoleon,

Wellington was constrained from sending his cavalry across the border. Merlen's Dutch/Belgian cavalry had captured several

French patrols, but were ordered by Wellington to escort them back across the frontier. This situation continued until 13th

June. Frustrated Prince of Orange wrote to Wellington: "I'm going to send back the French prisoners this morning with a

letter to General Count d'Erlon according to your wishes."

Napoleon decided to concentrate the army around Beaumont, storm Charleroi, cross the Sambre

River at this point and take the Prussians by surprise and defeat them. On 14th it was raining and the bivouacs were flooded.

Few campfires were carefully concealed from view. Part of the the infantry and engineers camped in the mist-drenched

woods.

Napoleon decided to concentrate the army around Beaumont, storm Charleroi, cross the Sambre

River at this point and take the Prussians by surprise and defeat them. On 14th it was raining and the bivouacs were flooded.

Few campfires were carefully concealed from view. Part of the the infantry and engineers camped in the mist-drenched

woods.

Charleroi owes its name to Charles II of Spain.

Its inhabitants live in a war zone for several centuries known what it is to be in the midst

of wars and sieges. Lachouque writes: "At that time they readily acclaimed Napoleon; but they

feared his soldiers, who had a reputation as pillagers and whose lack of discipline was well known.

They preferred the English, who were governed by an iron fist and who paid well.

However, everything is relative: they were prepared to welcome the French because they had chased

away the Prussians - brutal, mean, ravenous and hating anyone who spoke French."

Charleroi owes its name to Charles II of Spain.

Its inhabitants live in a war zone for several centuries known what it is to be in the midst

of wars and sieges. Lachouque writes: "At that time they readily acclaimed Napoleon; but they

feared his soldiers, who had a reputation as pillagers and whose lack of discipline was well known.

They preferred the English, who were governed by an iron fist and who paid well.

However, everything is relative: they were prepared to welcome the French because they had chased

away the Prussians - brutal, mean, ravenous and hating anyone who spoke French."

The Emperor set up his headquarters in a mansion where the lunch had been prepared for

Prussian General Hans Ernst Karl Graf von Ziethen-II.

The Red Lancers dismounted to water their horses, while the Guard Horse Chasseurs escorted

Napoleon. Napoleon was tired, he sat astride a chair and watched the cheerful Young Guard marching

past.

The Emperor set up his headquarters in a mansion where the lunch had been prepared for

Prussian General Hans Ernst Karl Graf von Ziethen-II.

The Red Lancers dismounted to water their horses, while the Guard Horse Chasseurs escorted

Napoleon. Napoleon was tired, he sat astride a chair and watched the cheerful Young Guard marching

past.

Ziethen's corps was in retreat towards Fleurus (near Ligny), he was falling back as slowly as possible

and protected the army concentrating at Sombreffe. Constant-Rebecque had kept his Netherlands divisions on the alert.

The British were quiet; Wellington read the despatches but thought the French attack on

Charleroi was a feint. The peasants informed Allies that Napoleon was with his Guard at

Charleroi. Marshal Ney pursued the Prussians and forced them to evacuate Gosselies, Frasnes and

Heppignies.

Ziethen's corps was in retreat towards Fleurus (near Ligny), he was falling back as slowly as possible

and protected the army concentrating at Sombreffe. Constant-Rebecque had kept his Netherlands divisions on the alert.

The British were quiet; Wellington read the despatches but thought the French attack on

Charleroi was a feint. The peasants informed Allies that Napoleon was with his Guard at

Charleroi. Marshal Ney pursued the Prussians and forced them to evacuate Gosselies, Frasnes and

Heppignies.

"It was not long before the first attack followed. Major von Haine led them advance to within 30 paces,

gave the order to fire, and the

"It was not long before the first attack followed. Major von Haine led them advance to within 30 paces,

gave the order to fire, and the  The Guard Dragoons avenged the death of their beloved Letort, the F/28th Infantry lost 13 officers and 614 men that day ! This battalion was then reorganised into a new

'combined battalion' with the survivors of the III/2nd Westphalian Landwehr which had suffered heavily on the retreat

from Thuin earlier on.

The Guard Dragoons avenged the death of their beloved Letort, the F/28th Infantry lost 13 officers and 614 men that day ! This battalion was then reorganised into a new

'combined battalion' with the survivors of the III/2nd Westphalian Landwehr which had suffered heavily on the retreat

from Thuin earlier on.

Napoleon despatched Marshal Ney with Reille's II Army Corps and Lefebvre-Desnouettes'

Guard Light Cavalry Division. At 6:30 PM the Red Lancers were receieved with musket

fire but after some quick maneuvers the enemy fell back. The hostile troops were Prince

Bernard of Saxe-Weimar's battalions. The Nassauers were alarmed by the exodus of peasants

and the artillery fire coming from the Fleurus direction.

Napoleon despatched Marshal Ney with Reille's II Army Corps and Lefebvre-Desnouettes'

Guard Light Cavalry Division. At 6:30 PM the Red Lancers were receieved with musket

fire but after some quick maneuvers the enemy fell back. The hostile troops were Prince

Bernard of Saxe-Weimar's battalions. The Nassauers were alarmed by the exodus of peasants

and the artillery fire coming from the Fleurus direction.

Night fell. Outside, the rain fell and swamped the rye-fields.

The men could neither eat nor sleep, and they were wallowing in water.

The chasseurs and hussars bivouacked in the mud together with lancers.

There were horses everywhere.

Night fell. Outside, the rain fell and swamped the rye-fields.

The men could neither eat nor sleep, and they were wallowing in water.

The chasseurs and hussars bivouacked in the mud together with lancers.

There were horses everywhere.

Napoleon's headquarters were set up in the small farm at Le Caillou.

A walled orchard that ran from the courtyard towards the north had already been

comandeered as a bivouac for the duty battalion (I/1st Chasseurs of the Old Guard) under

Duuring's command.

Napoleon's headquarters were set up in the small farm at Le Caillou.

A walled orchard that ran from the courtyard towards the north had already been

comandeered as a bivouac for the duty battalion (I/1st Chasseurs of the Old Guard) under

Duuring's command.

At 3:30 AM Wellington received a letter from Blucher. In it the Prussian general announced that he would be leaving at dawn and would attack

the enemy's right flank with one or perhaps three army corps. Lachouque writes: "The Duke experienced an immense feeling of relief ..."

At 3:30 AM Wellington received a letter from Blucher. In it the Prussian general announced that he would be leaving at dawn and would attack

the enemy's right flank with one or perhaps three army corps. Lachouque writes: "The Duke experienced an immense feeling of relief ..."

About 10 AM, Napoleon had Marshal Soult write the following letter to Marshal Grouchy:

About 10 AM, Napoleon had Marshal Soult write the following letter to Marshal Grouchy:

Bernard returned, hat in hand.

Bernard returned, hat in hand. Photo: wargamer's model of Hougoumont in 1815. Although NOT accurate in every detail,

it gives a good impression of what it looked like. Mark Adkin - "Waterloo Companion."

Photo: wargamer's model of Hougoumont in 1815. Although NOT accurate in every detail,

it gives a good impression of what it looked like. Mark Adkin - "Waterloo Companion."

Hougoumont was a robust compound surrounded by walls, with stables, barns, and houses.

There was a massive gate on the south side, leading to an inner courtyard.

Hougoumont was a robust compound surrounded by walls, with stables, barns, and houses.

There was a massive gate on the south side, leading to an inner courtyard.

General von Kruse writes: "About 9:30 AM ... the 1st Battalion of the regiment, received the

order to occupy the farm of Hougoumont that lay ahead of the centre of the right flank.

A company of Brunswick jager stood along the fence of the wood near the farm and, behind

the gardens, a battalion of the 2nd English Guard

Regiment."

General von Kruse writes: "About 9:30 AM ... the 1st Battalion of the regiment, received the

order to occupy the farm of Hougoumont that lay ahead of the centre of the right flank.

A company of Brunswick jager stood along the fence of the wood near the farm and, behind

the gardens, a battalion of the 2nd English Guard

Regiment."

Artillery of Reille's II Army Corps opened fire and the Allied batteries immediately responded.

Captain Sandham's Battery claims to have fired the first Allies cannon shot

of the battle - a claim disputed by Cleeve's Battery of King's German Legion.

At about midday, GdD Reille decided to send light infantry into the Hougoumont wood

and see what would happen. To begin the attack Reille selected Jerome's Bonaparte's division.

Artillery of Reille's II Army Corps opened fire and the Allied batteries immediately responded.

Captain Sandham's Battery claims to have fired the first Allies cannon shot

of the battle - a claim disputed by Cleeve's Battery of King's German Legion.

At about midday, GdD Reille decided to send light infantry into the Hougoumont wood

and see what would happen. To begin the attack Reille selected Jerome's Bonaparte's division.

Jerome did not owe his command to any particular military ability; in fact,

his performance as commander of the Westphalian troops during Napoleon's invasion of Russia

had been a failure. Within the army, Jerome was better known for his

scandalous American wife, whom Napoleon had refused to allow into France.

Jerome did not owe his command to any particular military ability; in fact,

his performance as commander of the Westphalian troops during Napoleon's invasion of Russia

had been a failure. Within the army, Jerome was better known for his

scandalous American wife, whom Napoleon had refused to allow into France.

The columns of the 1st Light were hit and their officers ordered them down into a little

lane-sunken that ran right along their front. The French officers started sending small

troops into the wood, where the skirmishers exchanged shots with the enemy. "At that moment there were about a thousand muskets at

Hougoumont, of which perhaps half were defending the perimeter of the park." (- A. Barbero)

The columns of the 1st Light were hit and their officers ordered them down into a little

lane-sunken that ran right along their front. The French officers started sending small

troops into the wood, where the skirmishers exchanged shots with the enemy. "At that moment there were about a thousand muskets at

Hougoumont, of which perhaps half were defending the perimeter of the park." (- A. Barbero)

Reille's artillery kept firing on all cylinders and several guns had been brought up

as far as the Nivelles Road. Almost all the British eyewitness accounts confirm that the

British and German infantry massed on the high ground beyond Hougoumont came under fire and

suffered a steady attrition that gradually began to wear on the men's nerves.

Reille's artillery kept firing on all cylinders and several guns had been brought up

as far as the Nivelles Road. Almost all the British eyewitness accounts confirm that the

British and German infantry massed on the high ground beyond Hougoumont came under fire and

suffered a steady attrition that gradually began to wear on the men's nerves.

The French began maneuvering around the flanks. Several columns moved across the plain

west of Hougoumont. They were under cover from horse battery that had advanced beyond ythe Nivelles Road.

Soye's men invaded the orchard, forcing the Germans and British Foot Guards to abandon it.

The guardsmen were chased back into the hollow way (bordered with thorny hedgerows)

that ran in front of the chateau.

The French began maneuvering around the flanks. Several columns moved across the plain

west of Hougoumont. They were under cover from horse battery that had advanced beyond ythe Nivelles Road.

Soye's men invaded the orchard, forcing the Germans and British Foot Guards to abandon it.

The guardsmen were chased back into the hollow way (bordered with thorny hedgerows)

that ran in front of the chateau.

Surprised by the appearance of Cubieres and his skirmishers the Foot Guards beat a hasty retreat, passing through the still-open gate into the farmyard

and closed the big door as fast as they could. Lieutenant Legros - nicknamed "The Smasher"

- took a sapper's axe and positioned himself before the gate.

He choped a hole through the door panel with an axe. Then the barrier yielded to the pressure of many

bodies, and a group of Frenchmen burst inside.

Surprised by the appearance of Cubieres and his skirmishers the Foot Guards beat a hasty retreat, passing through the still-open gate into the farmyard

and closed the big door as fast as they could. Lieutenant Legros - nicknamed "The Smasher"

- took a sapper's axe and positioned himself before the gate.

He choped a hole through the door panel with an axe. Then the barrier yielded to the pressure of many

bodies, and a group of Frenchmen burst inside.

Large group of French skirmishers climbed the slope in the direction of the British batteries,

concealing themselves amid the tall crops. In the course of few minutes many gunners and horses were hit

and the battery was forced to abandon the line of fire.

Large group of French skirmishers climbed the slope in the direction of the British batteries,

concealing themselves amid the tall crops. In the course of few minutes many gunners and horses were hit

and the battery was forced to abandon the line of fire.

"Between 2 and 3 PM, a [French] battery drew up on the right side of the buildings and began

to bombard them heavily with cannons and howitzers. It did not take long to set them all alight."

(- Major Busgen, Nassau Battalion)

"Between 2 and 3 PM, a [French] battery drew up on the right side of the buildings and began

to bombard them heavily with cannons and howitzers. It did not take long to set them all alight."

(- Major Busgen, Nassau Battalion)

The heavy skirmish fire and artillery bombardement continued to the last minutes of the battle

of Waterloo. For all its ferocity the fighting for Hougoumont was a subsidiary part of the day's events.

The heavy skirmish fire and artillery bombardement continued to the last minutes of the battle

of Waterloo. For all its ferocity the fighting for Hougoumont was a subsidiary part of the day's events.

Before 2 pm four infantry divisions of d'Erlon's corps began their advance.

Each division had two brigades of 4-6 battalions. For the first 500 m they marched not in

heavy columns but in narrow and long formations threading their way through the more than

200 limbers, and ammunition wagons that fed the 80 guns of French Grand Battery.

Before 2 pm four infantry divisions of d'Erlon's corps began their advance.

Each division had two brigades of 4-6 battalions. For the first 500 m they marched not in

heavy columns but in narrow and long formations threading their way through the more than

200 limbers, and ammunition wagons that fed the 80 guns of French Grand Battery.

Now the advance proper began and the French had to cover approx. 500 m separating them from

the enemy. The British, German and Netherland batteries (total of 29 pieces) fired as fast

as the gunners could reload. "In some cases, the gunners had forced open a passage for

their cannon through the hedge that bordered the sunken lane." The cannonballs tore through

the tightly packed ranks. Netherland and British skirmishers banged away and fell back, they

couldn't stop the French.

Now the advance proper began and the French had to cover approx. 500 m separating them from

the enemy. The British, German and Netherland batteries (total of 29 pieces) fired as fast

as the gunners could reload. "In some cases, the gunners had forced open a passage for

their cannon through the hedge that bordered the sunken lane." The cannonballs tore through

the tightly packed ranks. Netherland and British skirmishers banged away and fell back, they

couldn't stop the French.

The fight began on the left. One brigade of Allix/Quiot's division

came under heavy artillery and rifle fire from British riflemen in the sandpit and

from the "German riflemen on the roofs of La Haye Sainte causing it to veer slightly right.

The fight began on the left. One brigade of Allix/Quiot's division

came under heavy artillery and rifle fire from British riflemen in the sandpit and

from the "German riflemen on the roofs of La Haye Sainte causing it to veer slightly right.

General Picton spurred his horse "into the midst of Kempt's men and ordered a bayonet

assault: Charge ! Charge ! Hurrah !" Some French troops halted their advance, others not

- and all kept up their fire throughout.

General Picton spurred his horse "into the midst of Kempt's men and ordered a bayonet

assault: Charge ! Charge ! Hurrah !" Some French troops halted their advance, others not

- and all kept up their fire throughout.

When Sir Thomas Picton saw,

to his horror, that the Scots were starting to disband, he ordered one of his officers

to go and stop them. But when he was speaking to the officer a French soldier fired

and mortally wounded Picton. Officer's horse was wounded by another bullet

and collapsed.

When Sir Thomas Picton saw,

to his horror, that the Scots were starting to disband, he ordered one of his officers

to go and stop them. But when he was speaking to the officer a French soldier fired

and mortally wounded Picton. Officer's horse was wounded by another bullet

and collapsed.

Ltn. Scheltens of VII Belgian Line Battalion wrote: “Our battalion opened fire as our

skirmishers had come in. The French column was unwise enough to halt and begin to deploy.

We were so close that Cpt. Henry l’Olivuer, commanding our grenadier company, was struck

on the arm by a ball, of which the wad, or cartridge paper, remained smiking in the cloth

of his tunic … One French battalion commander had received a sabre cut on his nose, which

was hanging down over his mouth.”

Ltn. Scheltens of VII Belgian Line Battalion wrote: “Our battalion opened fire as our

skirmishers had come in. The French column was unwise enough to halt and begin to deploy.

We were so close that Cpt. Henry l’Olivuer, commanding our grenadier company, was struck

on the arm by a ball, of which the wad, or cartridge paper, remained smiking in the cloth

of his tunic … One French battalion commander had received a sabre cut on his nose, which

was hanging down over his mouth.”

The firefight was "protracted and effective" before the Dutch/Belgians fell back.

"Having approach us to within 50 paces not a shot had been fired, but now the impatience of

the soldiers could do no longer be restrained, and they greeted the enemy (French) with a

double row." (Col. van Zuylen van Nyevelt, chief-of-staff of 2nd Division)

The firefight was "protracted and effective" before the Dutch/Belgians fell back.

"Having approach us to within 50 paces not a shot had been fired, but now the impatience of

the soldiers could do no longer be restrained, and they greeted the enemy (French) with a

double row." (Col. van Zuylen van Nyevelt, chief-of-staff of 2nd Division)

Meanwhile other French brigade under Grenier marched against Pack's brigade.

Pack’s men did not attack the French until they had crossed over the hedge.

Meanwhile other French brigade under Grenier marched against Pack's brigade.

Pack’s men did not attack the French until they had crossed over the hedge.

The redcoats however rather than charge with lowered bayonets, "they too opened fire, inevitably

getting the worst of the exchange, so that they started to fall back in disorder,

while the men of the French 45th Line burst through the hedge en masse, yelling in triumph."

The redcoats however rather than charge with lowered bayonets, "they too opened fire, inevitably

getting the worst of the exchange, so that they started to fall back in disorder,

while the men of the French 45th Line burst through the hedge en masse, yelling in triumph."

The farms of Papelotte, La Haye, Fichermont and Smohain were defended by Prince Bernhard Saxe-Weimar's Netherland's brigade, actually made up of Germans in the

Orange Nassau and the 2nd Nassau Regiments. The soldiers were armed with French and British muskets.

(One of Prince Bernhard's battalions was sent to Hougoumont.)

The farms of Papelotte, La Haye, Fichermont and Smohain were defended by Prince Bernhard Saxe-Weimar's Netherland's brigade, actually made up of Germans in the

Orange Nassau and the 2nd Nassau Regiments. The soldiers were armed with French and British muskets.

(One of Prince Bernhard's battalions was sent to Hougoumont.)

Lord Uxbridge commanded Wellington's cavalry.

He was not only an excellent officer but also a womanizer. When he decided to elope with Wellington's sister-in-law

(and got her pregnant, before returning her to a tearful husband only to elope for a second time, forcing a parliamentary

divorce and then marrying the lady), the military establishment in London wrongly supposed that his talents were no longer

required by Wellington because of the scandal. Lord Uxbridge was a brave man, and well known general.

Lord Uxbridge commanded Wellington's cavalry.

He was not only an excellent officer but also a womanizer. When he decided to elope with Wellington's sister-in-law

(and got her pregnant, before returning her to a tearful husband only to elope for a second time, forcing a parliamentary

divorce and then marrying the lady), the military establishment in London wrongly supposed that his talents were no longer

required by Wellington because of the scandal. Lord Uxbridge was a brave man, and well known general.

Two regiments of French cuirassiers were still scattered, not having had time to reorder their

ranks after destroying the Luneberg Battalion near La Haye Sainte and chasing Ross' gunners.

Several small groups of cuirassiers crossed the main road.

They had no hope of resisting the sudden attack of three regiments of heavy cavalry led by

Somerset. The cuirassiers - after short fight - were thrown back by the guardsmen.

Two regiments of French cuirassiers were still scattered, not having had time to reorder their

ranks after destroying the Luneberg Battalion near La Haye Sainte and chasing Ross' gunners.

Several small groups of cuirassiers crossed the main road.

They had no hope of resisting the sudden attack of three regiments of heavy cavalry led by

Somerset. The cuirassiers - after short fight - were thrown back by the guardsmen.

When the dragoons of Union Brigade came to within 100-200 yards of Chemin d'Ohain,

they halted and allowed the retreating British and Netherland infantry to reach safety by passing

through the intervals between squadrons.

Ponsonby rode up to a vantage point and saw the French infantry was engaged in crossing the

sunken road. It was a perfect moment and Ponsonby ordered the charge.

When the dragoons of Union Brigade came to within 100-200 yards of Chemin d'Ohain,

they halted and allowed the retreating British and Netherland infantry to reach safety by passing

through the intervals between squadrons.

Ponsonby rode up to a vantage point and saw the French infantry was engaged in crossing the

sunken road. It was a perfect moment and Ponsonby ordered the charge.

Some officers tried to rally the dragoons and lead them back up the slope.

Many of the Scots Greys however decided that they had not yet had enough. They attacked the Grand Battery, or part of it.

There were no guns captured but many gunners were seized with panic by the sudden appearance

of the cavalry. (The gunners had stopped firing for fear of killing their own fleeing infantry.)

Some officers tried to rally the dragoons and lead them back up the slope.

Many of the Scots Greys however decided that they had not yet had enough. They attacked the Grand Battery, or part of it.

There were no guns captured but many gunners were seized with panic by the sudden appearance

of the cavalry. (The gunners had stopped firing for fear of killing their own fleeing infantry.)

The Germans of Ompteda's KGL Brigade, the Netherland soldiers of Bijlandt's brigade, and the

Scots and Englishmen of Pack's brigade advanced in support of the British dragoons and completed the roundup of prisoners.

The Germans of Ompteda's KGL Brigade, the Netherland soldiers of Bijlandt's brigade, and the

Scots and Englishmen of Pack's brigade advanced in support of the British dragoons and completed the roundup of prisoners.

Meanwhile the French lancers fanned out and started a mopping-up operation over the entire length

of the ground where catastrophe had struck Erlon's infantry.

The lancers fell on the British cavalry. Many dragoons dashed up the slope, and everyone

tried to save his own skin.

Sir Ponsonby together with his adjutant, Mjr Reignolds

made a dash to own line, and a French lancer began pursuing them.

While they were crossing a plowed field, Ponsonby's horse got stuck

in the mud and in an instant, the lancer was upon him.

Ponsonby threw his saber away and surrendered.

Meanwhile the French lancers fanned out and started a mopping-up operation over the entire length

of the ground where catastrophe had struck Erlon's infantry.

The lancers fell on the British cavalry. Many dragoons dashed up the slope, and everyone

tried to save his own skin.

Sir Ponsonby together with his adjutant, Mjr Reignolds

made a dash to own line, and a French lancer began pursuing them.

While they were crossing a plowed field, Ponsonby's horse got stuck

in the mud and in an instant, the lancer was upon him.

Ponsonby threw his saber away and surrendered.

General Trip led three regiments of Dutch and Belgian carabiniers against the French

cuirassiers. The 1st (Dutch) Carabiniers were led by Lt-Col. Coenegracht, the 2nd (Belgian) Carabiniers by

Col. de Bruijn, and the 3rd (Dutch) Carabiniers by Lt-Col. Lechleitner.

The two sides met each other west of La Haye Sainte. Then the two lines clashed and after a short fight the

French fell back to the bottom of the slope.

General Trip led three regiments of Dutch and Belgian carabiniers against the French

cuirassiers. The 1st (Dutch) Carabiniers were led by Lt-Col. Coenegracht, the 2nd (Belgian) Carabiniers by

Col. de Bruijn, and the 3rd (Dutch) Carabiniers by Lt-Col. Lechleitner.

The two sides met each other west of La Haye Sainte. Then the two lines clashed and after a short fight the

French fell back to the bottom of the slope.

The Allied generals and officers, with fieldglasses in hand, realized that the French cavalry was

preparing to advance in even greater strength.

The Allied generals and officers, with fieldglasses in hand, realized that the French cavalry was

preparing to advance in even greater strength.

The French charged, routed the skirmishers and captured several batteries and was

in possession of the Mont-Saint-Jean ridge. In front of them were Allied infantry formed in squares.

The infantry opened fire and repulsed the cavalry. The French regrouped and began advance again.

"Sometimes, this psychological game took on comedic rhythms.

The Duke of Wellington recalled having seen some squares which 'would not throw away

their fire until the cuirassiers charged, and they would not charge until we had thrown

away our fire.'

The French charged, routed the skirmishers and captured several batteries and was

in possession of the Mont-Saint-Jean ridge. In front of them were Allied infantry formed in squares.

The infantry opened fire and repulsed the cavalry. The French regrouped and began advance again.

"Sometimes, this psychological game took on comedic rhythms.

The Duke of Wellington recalled having seen some squares which 'would not throw away

their fire until the cuirassiers charged, and they would not charge until we had thrown

away our fire.'

Ensign Gronow of British 1st Foot Guard writes: "Our squares presented a shocking sight. Inside we were nearly

suffocated by the smoke and smell from burnt cartridges. It was impossible to move a yard without treading upon a

wounded comrade, or upon the bodies of the dead; and the load groans of the wounded and dying was most appaling.

At 4 o'clock our square was a perfect hospital, being full of dead, dying, and mutilated bodies." Wellington himself

took refuge in this square. He appeared very "thoughtful and pale."

Ensign Gronow of British 1st Foot Guard writes: "Our squares presented a shocking sight. Inside we were nearly

suffocated by the smoke and smell from burnt cartridges. It was impossible to move a yard without treading upon a

wounded comrade, or upon the bodies of the dead; and the load groans of the wounded and dying was most appaling.

At 4 o'clock our square was a perfect hospital, being full of dead, dying, and mutilated bodies." Wellington himself

took refuge in this square. He appeared very "thoughtful and pale."

The British claim that not a single square was broken. Siborne wrote that

one square had a side "completely blown away and dwindled

into a mere clump."

The British claim that not a single square was broken. Siborne wrote that

one square had a side "completely blown away and dwindled

into a mere clump."

At Waterloo Wellington's troops garrisoned several strongpoints: La Haye Sainte, Hougoumont,

Papelotte and La Haye. There were several differences between Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte.

Hougoumont was a much more substantial complex, it could shelter a garrison of 2,000

infantrymen, while within the perimeter of La Haye Sainte Mjr. Baring had less than 500 men.

At Waterloo Wellington's troops garrisoned several strongpoints: La Haye Sainte, Hougoumont,

Papelotte and La Haye. There were several differences between Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte.

Hougoumont was a much more substantial complex, it could shelter a garrison of 2,000

infantrymen, while within the perimeter of La Haye Sainte Mjr. Baring had less than 500 men.

"Unlike Hougoumont, whose possesion was

not critical to either side, La Haye Sainte was vital to both. ... A garrison of 400 indicates

that it is likely Wellington underestimated its importance, at least initially. And whoever

ordered Baring's pioneers and tools to Hougoumont on the night of 17/18 June had not got

his tactical thinking straight... The bungled ammunition supply was another indication that

the Anglo-Allied high command only belatedly appreciated the significance of this outpost...

Because Baring lacked both tools and timber, the loopholes were few and there were no platforms

built behind the walls... This meant that shooting over the walls was often not possible,

and seriously restricted through them." (Mark Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" pp 374, 376)

"Unlike Hougoumont, whose possesion was

not critical to either side, La Haye Sainte was vital to both. ... A garrison of 400 indicates

that it is likely Wellington underestimated its importance, at least initially. And whoever

ordered Baring's pioneers and tools to Hougoumont on the night of 17/18 June had not got

his tactical thinking straight... The bungled ammunition supply was another indication that

the Anglo-Allied high command only belatedly appreciated the significance of this outpost...

Because Baring lacked both tools and timber, the loopholes were few and there were no platforms

built behind the walls... This meant that shooting over the walls was often not possible,

and seriously restricted through them." (Mark Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" pp 374, 376)

La Haye Sainte was defended by one battalion from Ompteda's 2nd KGL Brigade.

This battalion (II Light Battalion) was commanded by Major George Baring.

He was a seasoned officer, with at least 10 years active duty.

The second in command was Major Bosewiel.

La Haye Sainte was defended by one battalion from Ompteda's 2nd KGL Brigade.

This battalion (II Light Battalion) was commanded by Major George Baring.

He was a seasoned officer, with at least 10 years active duty.

The second in command was Major Bosewiel.

Around 1.30 PM the French tirailleurs (of Charlet's brigade) attacked and captured the orchard. The German riflemen retired into the buildings. The musket and rifle fire was such

that soon the farm was surrounded and covered by white smoke. Bosewiel was killed.

The divisional commander, von Alten, ordered up the Luneberg Light Battalion of 8 companies

(under von Klencke) and 2 companies of I Light KGL (under von Gilsa and Marszalek)

to counter-attack so they might relieve the pressure on La Haye Sainte.

Around 1.30 PM the French tirailleurs (of Charlet's brigade) attacked and captured the orchard. The German riflemen retired into the buildings. The musket and rifle fire was such

that soon the farm was surrounded and covered by white smoke. Bosewiel was killed.

The divisional commander, von Alten, ordered up the Luneberg Light Battalion of 8 companies

(under von Klencke) and 2 companies of I Light KGL (under von Gilsa and Marszalek)

to counter-attack so they might relieve the pressure on La Haye Sainte.

The French seeing that the Germans' fire was growing lighter,

attacked the side of the farm nearest the road, and sappers armed with axes

started knocking down the carriage gate. It was officer Vieux of engineers

who finally knocked down the gate.

The French eventually broke in through the stable passage and barn entrance in the west.

Shortly afterwards the main gate, underneath the dovecote, was battered down with axes

wielded by men of the 1st Engineer Regiment and stormed by the II Battalion of 13th Light Regiment from Donzelot's

2nd Division.

The French seeing that the Germans' fire was growing lighter,

attacked the side of the farm nearest the road, and sappers armed with axes

started knocking down the carriage gate. It was officer Vieux of engineers

who finally knocked down the gate.

The French eventually broke in through the stable passage and barn entrance in the west.

Shortly afterwards the main gate, underneath the dovecote, was battered down with axes

wielded by men of the 1st Engineer Regiment and stormed by the II Battalion of 13th Light Regiment from Donzelot's

2nd Division.

The riflemen attempted to block up holes in the walls made by artillery fire but the French

scaled the walls and bursted into the farmyard. Mjr. Baring gave order to retire through the house into the garden. They rushed to the rear

with the French hot on their heels.

The riflemen attempted to block up holes in the walls made by artillery fire but the French

scaled the walls and bursted into the farmyard. Mjr. Baring gave order to retire through the house into the garden. They rushed to the rear

with the French hot on their heels.

The French continued their advance and their sudden appearance provoked panic and

consternation among the KGL and British squares. Wellington rode up to this point

and watched the French for a while.

The French continued their advance and their sudden appearance provoked panic and

consternation among the KGL and British squares. Wellington rode up to this point

and watched the French for a while.

Ompteda took V Line KGL and led them from the front.

They boldly advanced dispersing French tirailleurs before them but then somebody

cried out "Cavalry !" The French tirailleurs turned back and attacked. Ompteda

and Ltn. Wheatley were surrounded by cavalry and infantry. Soon one of them was dead with a

musket ball in his mouth, and the other lost consciousness and was taken prisoner by the

French. "I saw Colonel Ompteda, in the midmost throng of the enemy

infantry and cavalry, sink from his horse and vanish." (- Captain Berger, V KGL Line Btn.)

Ompteda took V Line KGL and led them from the front.

They boldly advanced dispersing French tirailleurs before them but then somebody

cried out "Cavalry !" The French tirailleurs turned back and attacked. Ompteda

and Ltn. Wheatley were surrounded by cavalry and infantry. Soon one of them was dead with a

musket ball in his mouth, and the other lost consciousness and was taken prisoner by the

French. "I saw Colonel Ompteda, in the midmost throng of the enemy

infantry and cavalry, sink from his horse and vanish." (- Captain Berger, V KGL Line Btn.)

If the Prussians had fallen back on their communication lines after Ligny,

Wellington would almost certainly have had have fallen back on his, which ultimately meant

reatreat to the channel coast with a view to re-embarking a la Dunkirk.

The object of offering battle at Waterloo was to hold Napoleon until the Prussians arrived.

[In the classic British version of Waterloo the Prussians arrived just in time to mop up the

battlefield.]

If the Prussians had fallen back on their communication lines after Ligny,

Wellington would almost certainly have had have fallen back on his, which ultimately meant

reatreat to the channel coast with a view to re-embarking a la Dunkirk.

The object of offering battle at Waterloo was to hold Napoleon until the Prussians arrived.

[In the classic British version of Waterloo the Prussians arrived just in time to mop up the

battlefield.]

At 4 PM all the cavalry and half of the infantry of Bulow's IV Corps were ready to fall upon the French.

Several batteries were pushed forward.

"The wounded, as we came rushing on, set up a dreadful crying, and holding up their hands entreated us, some in French and some

in English, not to crush their already mangled bodies beneath our wheels. It was a terrible

sight to see those faces with the mark of death upon them, rising from the ground and the arms

outstretched towards us." (- Kpt. von Reuter)

At 4 PM all the cavalry and half of the infantry of Bulow's IV Corps were ready to fall upon the French.

Several batteries were pushed forward.

"The wounded, as we came rushing on, set up a dreadful crying, and holding up their hands entreated us, some in French and some

in English, not to crush their already mangled bodies beneath our wheels. It was a terrible

sight to see those faces with the mark of death upon them, rising from the ground and the arms

outstretched towards us." (- Kpt. von Reuter)

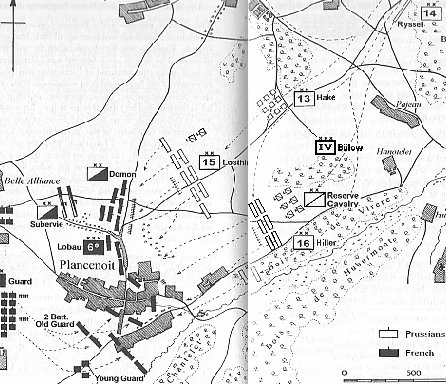

Bulow writes: "It was half past four in the afternoon, when the head of our column advanced out of the Frichermont wood.

The 15th Brigade under Gen. von Losthin deployed quickly into battalion columns, throwing out skirmishers.

The brigade's artillery, along with the Reserve Artillery (of Bulow's Corps), followed up rapidly, seeking to gain the gentle ridge."

Bulow writes: "It was half past four in the afternoon, when the head of our column advanced out of the Frichermont wood.

The 15th Brigade under Gen. von Losthin deployed quickly into battalion columns, throwing out skirmishers.

The brigade's artillery, along with the Reserve Artillery (of Bulow's Corps), followed up rapidly, seeking to gain the gentle ridge."

Two battalion columns of 15th Regiment pushed into the village and then on the high walls of the cemetary

and church.

The Prussians found themselves under fire from French snipers stationed in the houses.

The French had brought canons and howitzers into the streets "where close range blasts of canister would blow away oppositions

as a gale does autumn leaves." The Prussians however pressed forward and captured 3 cannons and several

hundred prisoners. (Bulow is however wrong claiming that already in this stage they were counterattacked by the Old Guard.)

Two battalion columns of 15th Regiment pushed into the village and then on the high walls of the cemetary

and church.

The Prussians found themselves under fire from French snipers stationed in the houses.

The French had brought canons and howitzers into the streets "where close range blasts of canister would blow away oppositions

as a gale does autumn leaves." The Prussians however pressed forward and captured 3 cannons and several

hundred prisoners. (Bulow is however wrong claiming that already in this stage they were counterattacked by the Old Guard.)

By 5 PM the 1st Brigade of Ziethen's I Corps had reached Lasne brook.

Ziethen's chief of staff rode on to the battlefield and met Muffling,

who informed him that the Duke was desperate for his help.

A Prussian officer was sent on to examine the situation. He saw many wounded and stragglers retreating from Wellington's positions, while the

French seemed to be pressing home their advantage.

By 5 PM the 1st Brigade of Ziethen's I Corps had reached Lasne brook.

Ziethen's chief of staff rode on to the battlefield and met Muffling,

who informed him that the Duke was desperate for his help.

A Prussian officer was sent on to examine the situation. He saw many wounded and stragglers retreating from Wellington's positions, while the

French seemed to be pressing home their advantage.

The Prussians emerged from the burning remains of village carrying their shakos on their muskets

and singing. At this point the French army disintegrated completely.

Darkness began to fall and the number of fugitives rapidly

increased. Some were fleeing toward positions where stood Napoleon's last reserve,

three btns. of Old Guard and part of Emperor's baggage. Escorted by Prussian uhlans,

an infantry drummer was mounted on one of

the horses of Napoleon's retinue.

The Prussians emerged from the burning remains of village carrying their shakos on their muskets

and singing. At this point the French army disintegrated completely.

Darkness began to fall and the number of fugitives rapidly

increased. Some were fleeing toward positions where stood Napoleon's last reserve,

three btns. of Old Guard and part of Emperor's baggage. Escorted by Prussian uhlans,

an infantry drummer was mounted on one of

the horses of Napoleon's retinue.

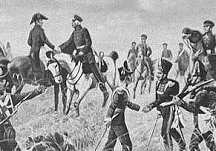

On June 19, 1815 Wellington wrote to Bathurst on the actions of Prussian Army on Napoleon’s

right flank and during pursuit after battle describing them as the "most decisive."

Blücher suggested to Wellington that they call it the Battle of La Belle Alliance, but

Wellington had other plans. He raced back to his headquarters and wrote his famous dispatch,

explaining just how he had won the Battle of Waterloo.

On June 19, 1815 Wellington wrote to Bathurst on the actions of Prussian Army on Napoleon’s

right flank and during pursuit after battle describing them as the "most decisive."

Blücher suggested to Wellington that they call it the Battle of La Belle Alliance, but

Wellington had other plans. He raced back to his headquarters and wrote his famous dispatch,

explaining just how he had won the Battle of Waterloo.

The marks of the saber still remain upon one of the carriage springs; the gallant Prussian then forced open one of the doors of the carriage, but in the interval, Napoleon had escaped by the opposite door; and thus disappointed

the triumphant hopes of that gallant officer. Such, however, was the haste of the Ex-Emperor,

that he dropped his hat, his sword, and his mantle, and they were afterwards

picked up on the road." (- "Waterloo Memoirs", London 1817, Vol II, pp 32-37)

The marks of the saber still remain upon one of the carriage springs; the gallant Prussian then forced open one of the doors of the carriage, but in the interval, Napoleon had escaped by the opposite door; and thus disappointed

the triumphant hopes of that gallant officer. Such, however, was the haste of the Ex-Emperor,

that he dropped his hat, his sword, and his mantle, and they were afterwards

picked up on the road." (- "Waterloo Memoirs", London 1817, Vol II, pp 32-37)

After its capture by Maj von Keller on 18 June 1815, William Bullock acquired the carriage.

It greatly aroused the curiosity of the English people and they flocked to see items that were once His.

Painted a dark blue, the dormeuse was embellished with frieze ornament in gold.

The undercarriage and wheels were in blue and heightened in gold. The wheels, tyres and undercarriage were designed for strength.

The exhibit was a tremendous success earning William Bullock 35,000 pounds !

The carriage was exhibited for many years at Madame Tussaud's waxwork museum in London,

where it was destroyed by fire after World War I.

It was never presented neither in Germany nor in Prussia, the country

of officer von Keller.

After its capture by Maj von Keller on 18 June 1815, William Bullock acquired the carriage.

It greatly aroused the curiosity of the English people and they flocked to see items that were once His.

Painted a dark blue, the dormeuse was embellished with frieze ornament in gold.

The undercarriage and wheels were in blue and heightened in gold. The wheels, tyres and undercarriage were designed for strength.

The exhibit was a tremendous success earning William Bullock 35,000 pounds !

The carriage was exhibited for many years at Madame Tussaud's waxwork museum in London,

where it was destroyed by fire after World War I.

It was never presented neither in Germany nor in Prussia, the country

of officer von Keller.

At Waterloo, Napoleon ran the show until the Prussians arrived.

Fighting against two armies at once was too much even for Napoleon, and the French folded.

At Waterloo, Napoleon ran the show until the Prussians arrived.