|

.

At Quatre Bras an officer of the British 28th Foot

recalled that when his unit was in square

a French lancer was sent forward to plant his lance

with its pennon in front of the battalion as a marker

for his unit to charge on."

Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 154

|

The Lancers.

The Poles had fueled a "lance craze" that swept the armies of Europe

and inspired tens of regiments to clad in outfits modeled

on the uniform of the Polish uhlans.

The Polish Guard lancers knew how to fight and they intended to do just that.

It was Napoleon who said: "These men only know how to fight !" after

they charged in their usual impetous, stormy fashion at Somosierra.

The Poles used to say that every commander loved the lancers for their looks,

but not every man wished to carry the heavy weapon for all year long.

The lance was traditional weapon of the Poles. First the Polish legendary Winged Knights

(husaria) used it with great success against their enemies. Husaria's lance was

approx. 5 m long. They attacked frontally smashing everything on their way.

The times changed and the Winged Knights were replaced with uhlans (ulani) - armed with

2.5 m long lances. During march the weight of the lance bore down on the stirrup, where its lower

end fitted into a small 'bucket'; carried on the march slanting back from a small sling around

the rider's arm.

The Poles used to say that every commander loved the lancers for their looks,

but not every man wished to carry the heavy weapon for all year long.

The lance was traditional weapon of the Poles. First the Polish legendary Winged Knights

(husaria) used it with great success against their enemies. Husaria's lance was

approx. 5 m long. They attacked frontally smashing everything on their way.

The times changed and the Winged Knights were replaced with uhlans (ulani) - armed with

2.5 m long lances. During march the weight of the lance bore down on the stirrup, where its lower

end fitted into a small 'bucket'; carried on the march slanting back from a small sling around

the rider's arm.

Mastery with lance required training and strong hand. "It took a lot of extra

training to produce a competent lancer. A British training manual produced some years after

Waterloo stated that he had to master 55 different exercises with his lance - 22 against

cavalry, 18 against infantry, with 15 general ones thrown in for good measure."

(Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 247)

Giving lances to poorly trained men didn't make them good lancers, they were 'men with sticks'

not uhlans. Lancer was a formidable opponent. Before World War I Mr. Wilkinson "have watched and recorded hundreds of competitions between

men equally experts in the use of their weapons but lance won by the every large majority

of them."

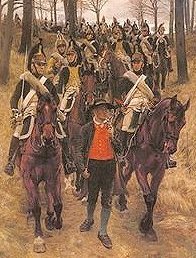

In 1809 in Vienna, Polish NCO Jordan of Guard Lighthorse, called upon dragoons of Napoleon's

Old Guard, to "fight" him. Two battle-hardened veterans

stepped out, he unhorsed both. (see picture -->)

In 1809 in Vienna, Polish NCO Jordan of Guard Lighthorse, called upon dragoons of Napoleon's

Old Guard, to "fight" him. Two battle-hardened veterans

stepped out, he unhorsed both. (see picture -->)

The friendly duel was watched by Napoleon, Marshal Murat and several French generals.

Napoleon was impressed with the Polish lancers and ordered the formation

of nine regiments of lancers in his army. In the memoirs of Waterloo, the French lancers,

galloping at will over the battlefield, sending saber-armed cavalry fleeing before them, and calmly stopping to finish off the

wounded without even having to dismount, appear as an image of horror. Wyndham of the Scots

Grays saw the lancers pursuing British dragoons who had lost their mounts and were trying to

save themselves on foot. He noted the ruthlessness of the lancers' pursuit and watched them

cut their victims down.

The Poles had fueled a "lance craze" that swept the armies of Europe

and inspired tens of regiments to clad in outfits modeled on the uniform of the uhlans.

The Russians increased number of uhlan regiments from 5-6 to 12 and armed their 12 hussar

regiments with lances. The Austrians increased from 3 to 4 regiments and the Prussians

from 1 to 8 regiments. All lancers were uniformed in Polish style and design.

Even the British formed their own lancers styled on the Poles. Uhlans were also formed in

Italy and Spain.

Right: the legendary charge of British lancers at Balaklava, October 25th 1854.

Their uniforms closely resembled the dress of the Polish Vistula uhlans.

Right: the legendary charge of British lancers at Balaklava, October 25th 1854.

Their uniforms closely resembled the dress of the Polish Vistula uhlans.

Left: German lancers in 20th Century.

In 1914 the German Army included nineteen uhlan regiments, and there were eleven regiments of uhlans in the

Austro-Hungarian cavalry. The Russians also had cavalry armed with lances.

Uhlan units took part in the massive cavalry battle at Komarow of 1920, the last pure cavalry battle in history.

In the period between the world wars, the Polish uhlan units were reformed. They employed infantry tactics: the men

dismounted before the battle and fought as infantry using modern rifles, field guns and light tanks.

The story of heroic Polish uhlans attacking German tanks during WW2 is a myth.

On Sept 1st 1939 at Krojanty part of Polish 18th Uhlan Regiment successfully charged German infantry battalion resting near woods

but then got under heavy machine gun fire and withdrew. According to

General Heinz Guderian this charge impressed the Germans and caused a wide spread panic among the

staff and infantry. The same day the German war correspondents were brought to the

battlefield together with two journalists from Italy. They were shown the battlefield, the corpses of uhlans and their horses, as well as German tanks that arrived to the

place after the battle. One of the Italian correspondents sent home an article, in which he

described the bravery of the uhlans, who charged German tanks with sabres and lances.

Although such a charge did not happen and there were no tanks used during the combat, the myth

was used by German propaganda during the war. One film even showed a cavalry charge on tanks, with Polish uhlans (in German helmets and

uniforms) using their lances against tanks.

The story of heroic Polish uhlans attacking German tanks during WW2 is a myth.

On Sept 1st 1939 at Krojanty part of Polish 18th Uhlan Regiment successfully charged German infantry battalion resting near woods

but then got under heavy machine gun fire and withdrew. According to

General Heinz Guderian this charge impressed the Germans and caused a wide spread panic among the

staff and infantry. The same day the German war correspondents were brought to the

battlefield together with two journalists from Italy. They were shown the battlefield, the corpses of uhlans and their horses, as well as German tanks that arrived to the

place after the battle. One of the Italian correspondents sent home an article, in which he

described the bravery of the uhlans, who charged German tanks with sabres and lances.

Although such a charge did not happen and there were no tanks used during the combat, the myth

was used by German propaganda during the war. One film even showed a cavalry charge on tanks, with Polish uhlans (in German helmets and

uniforms) using their lances against tanks.

(The Polish Uhlan Brigades were equipped with anti-tank guns such as 37mm Bofors wz.36 (exported to UK

as Ordnance Q.F. 37mm Mk I) that could penetrate tanks' armor. At Krojanty they just made a surprising

attack on resting infantry and withdrew before machine guns.)

Left: German SS Geyer Cavalry Division in 1942.

The Division saw action on the Eastern Front, in areas such as Briansk, Viazma and the mighty

Battle of Moscow.

Left: German SS Geyer Cavalry Division in 1942.

The Division saw action on the Eastern Front, in areas such as Briansk, Viazma and the mighty

Battle of Moscow.

Right: British 16th Lancer Regiment in 1914.

In 1914 at Moncel the British 9th Lancers attacked Prussian Guard Dragoons.

Lancers' casualties were 10 killed and wounded compared to heavy losses suffered by the

Prussians. The 9th (Queen's Royal) Lancers was originally one of the dragoon regiments and served under Wellington in Spain.

"After 1816 they became Lancers, on the model of the celebrated Polish Lancers, who rendered Napoleon such devoted

service."

French officer de Brack on lance.

Q: Is the lance a very effective weapon?

A: Its moral effect is the greatest, and its thrusts the most murderous of all weapons.

Q: In war, should the use of the lance conform to the directions contained in the regulations?

A: No; as a general rule the trooper must consider himself the centre of a circle whose circumference is described by the point of his weapon; but the lancer must limit his points to the half-circle in his front, and cover the rear half by the "around parry."

Q: Why?

A: The points are certain only so long as the nails are up and the forearm and body control the direction of the weapon. Where these two indispensable conditions do not exist, points which the enemy might easily parry, and which might disarm you, should not be risked. The very least objection to thrusts thus hazarded would be their uselessness, and, in war, uselessness is the synonym of ignorance and danger.

Q: What then are the "points" to which one should confine himself in action?

A: The "right-front" and "left-front" points; the "right" and "left" points against infantry; the "right," "left," and "around parries."

Q: But, should the hostile cavalry follow and press you closely?

A: Use against them the "right," "left," and "around parries," which become powerful offensive movements, when properly employed. In fact, the point cannot fail to reach the man, or the head of his horse, and the weight of the arm doubling the force of its impulsion, the enemy will be at once overthrown, or the horse be immediately stopped by the thrust.

I have witnessed a hundred illustrations of the truth of this, and, among others, may cite the case of the intrepid Captain Brou (now Colonel of the 1st Lancers), who, while near Eylau, in a charge which we made upon the Cossacks, believed himself already master of one of them, whom he had taken on his left side, and who held his lance at a "right front;" but the Cossack, standing up in his stirrups, and executing rapidly an "around parry," threw the Captain to the ground; his horse was captured, and he would have been made prisoner also, but for a courageous and skilfully executed charge made by Major Hulot, then commanding the 7th Hussars. I saw the Captain's wound dressed, and his shoulder was gashed as though cut with the edge of a sabre.

…. I have seen old Cossacks, charged by our troops with their short weapons, face and await them firmly, the point of the lance not to the front, because they judged from the boldness of the attack that their points would be parried - and that once closed in upon they would be lost - but with the lance to the right front, as in the first motion of "left parry," then responding to the attack with a "left parry," brush aside the attackers by this movement, volt to the left, and find themselves, in their turn, naturally taking the offensive by pursuing the enemy on his left.

Q: How should lance thrusts be made in action?

A: I repeat, the lance must always be held with the whole hand closed upon it, the fingers upwards, and no movement requiring the fingers to be held downwards, should be attempted, because the weight of the weapon may cause it, if parried by the enemy, to escape from the hand.

… To carry the hand to the rear only to thrust it forward again, is both useless and dangerous. Your point will always have enough spring, strength, and reach to traverse the body of a man.

… In campaign an officer should frequently inspect his lances, and see that they are kept sharp and well greased. Wounds made in the body by lances kept in good condition are almost always mortal. I have seen troopers of our army receive as many as twenty wounds, made by Cossack lances, without dying of them or even being disabled.

Q: To what do you attribute that?

A: To the inferior quality of the Cossack weapons, to the little care taken of them, and, above all, to a cause worth while to explain. The lances of the Cossacks who used to fight against us were not shod at the butt end, so, when the lancer dismounted, to avoid leaving the lance lying on the ground, he stuck the point into the soil, and thus blunted it. Hence you will remember that, under no pretext, are you to stick the point of your lance into the ground, and that it would be a hundred times better to throw it on the ground than to keep it standing up at such a cost.

The French lance needs improvement; the ash of which the staff is made is so heavy that it makes it difficult to handle, and, when carried in the socket, injures the horse's withers. The wood does not, by its strength, compensate for this disadvantage; for being cut in blocks and the grain crossed, it breaks easily and in a way that makes repairing difficult.

Another fault is the too great size of the pennons which present to the wind so large a surface that the staves are quickly bent, so that points cannot be made as accurately as they should be; quickness and lightness in handling them are diminished, and on the road the horse and the lancer's arm are uselessly fatigued by the constant backward pressure.

To correct these faults, in route marches the pennons should be removed, and attached only when it is desired to make ourselves recognized by friends or enemies; to shift the lance alternately from the right boot to the left, and frequently to remove it entirely from the boot, so that it may be carried by the lancer himself.

The rolled coat may be considered a defensive weapon. The habit of rolling it, and crossing it over the chest, in view of an engagement, has three advantages: first, it clears the opening of the pistol holster; second, it allows the bridle hand to be carried nearer to the horse's neck, which facilitates the control of the horse; and, third, it protects the trooper. But the trooper must be careful of two things: first, to so roll and cross his coat as not to be constrainted by it, and, second, in a charge to avoid being seized by it, and unhorsed and captured.

Although to lose one's arms is, generally speaking, a shame, yet there is one case where a lancer is excusable for losing his lance - that is, when he has run it clean through an enemy.

Several times, I have seen lances so well used that the weapon, caught between the ribs, after having penetrated the shoulder blade, could not possibly be withdrawn; the dying man, convulsed with pain, carried away by his horse, drew along with him the lance and the lancer vainly struggling to disengage his weapon. At Reichenbach, the bravest lancer of my regiment was killed under similar circumstances, in disobedience of my orders, through a misunderstood, stubborn sense of honor. In vain I called out to him, "Your lance is well lost"; he did not believe me, and being cut off from his comrades, was overwhelmed by numbers, and killed.

Near Lille, a young soldier of the same regiment found himself in a similar condition; I made him abandon his lance. The Prussian whom he had run through fell about 50 paces from the spot where he was wounded; we retook the ground which he had been obliged to yield for a few minutes, and my lancer having dismounted to recover his lance, succeeded in doing so only by carefully pushing it through in the same direction in which it entered.

At Waterloo, when we charged the English squares, one of our lancers, not being able to break down the rampart of bayonets which opposed us, stood up in his stirrups and hurled his lance like a spear; it passed through an infantry soldier, whose death would have opened a passage for us, if the gap had not been quickly closed. That was another lance well lost. “

Lancers vs Cavalry.

Lance was the most dangerous in the

first contact during line-vs-line combats.

Lance was the most dangerous in the first contact during line-vs-line combats.

The long weapon allowed cavalrymen to wound or kill an enemy armed with shorter weapon first.

Once the enemy had got past the point of the lance then the lancer was vulnerable.

General Jomini wrote that lance is the most aggressive weapon as one can simply outreach

every opponent.

Lance was the most dangerous in the first contact during line-vs-line combats.

The long weapon allowed cavalrymen to wound or kill an enemy armed with shorter weapon first.

Once the enemy had got past the point of the lance then the lancer was vulnerable.

General Jomini wrote that lance is the most aggressive weapon as one can simply outreach

every opponent.

Jomini writes: "Much discussion has taken place about the proper manner of arming

cavalry. The lance is the best arm for offensive purposes when a body of horsemen charge in

line; for it enables them to strike an enemy who cannot reach them; but it is a very good plan

to have a second rank ... armed with sabers, which are more easily handled than the lance in

hand-to-hand fighting when the ranks become broken. It would be , perhaps, better still to

support a charge of lancers by a detachment of hussars... the advantegeous use of lance

depends upon the preservation of good order..."

De Rocca described how lancers were defeated:

"... they [Spaniards] marched in close column; at their head were the lancers of Xeres. This whole body began

at once to quicken their pace, in order to charge us while we were retiring. The captain commandimg our squadron made his

four platoons ... wheel half round to the right. This movement being made, he adjusted the front line of his troop

as quietly as if we had not been in presence of the enemy. ... The Spanish horse, seized with astonishment at his coolness, involuntarily slackened their pace.

Our commandant ... ordered the charge to be sounded. Our hussars, who in the midst of the threats and abuse of the enemy had preserved the strictest silence, then drowned

the sound of the trumpet as they moved onwards ... The Spanish lancers stopped;

seized with terror, they turned their horses at the distance of half-pistol-shot,

... our hussars mingled with them indiscriminately ..."

But more often than not the lancers routed the hussars.

In 1815 near Gosselies the excellent French 1st Hussars met Prussian 6th Uhlans and 24th Infantry.

The uhlans attacked and drove the hussars back in disorder, only to be attacked in turn by French lancers

of Pire's division. Heinrich Niemann of 6th Uhlans writes: "By command of Gen. Ziethen we engaged the French; but it was nothing

more than a feint; they retreated before us."

Disadvantages of lance:

Disadvantages of lance:

- the preservation of good order was a must for the lancers.

It was however difficult to keep order during charge, as abandoned equipment, trees and

bushes, falling horses, stress and over-excitement could put the riding men into disorder.

It was one of the reasons why not all cavalry were lancers, and not every uhlan charge was successful.

The regulations for Saxon cavalry recommended an unusual attack against the lancers.

It was called a la debandade and was executed in the widest intervals and only by the

hussars (excellent horsemen and swordsmen) or cuirassiers (with body armor).

The wide intervals allowed them to get behind the lancers. It was assumed that the

effectiveness of the lance was reduced because the target was not concentrated and the lancer

would have to constantly aim his lance at a moving target rather than just point it forward.

- in a melee where one has to parry blows from the left, right and

rear and do it quickly the lance was too long and too heavy. In such situation many

lancers discarded their weapons and fought with sabers. It happened in 1809 at Wagram

where the Austrian uhlans threw away their lances after being attacked by Polish Guard

lighthorsemen (not yet armed with lances).

According to the Journal of Prussian 1st Leib Hussar Regiment: "When a lance-armed cavalry

is charged home and when the melee begins, it is lost when opposed by any other cavalry

armed with shorter arms. Proof for this is given by the attack of the regiment on the 2nd

and 4th Polish Lancers at Dennewitz. Both regiments belonged to the cream of the French

army. They were defeated easily, we took 10 officers and 120 others prisoner,

the battlefield was covered with dead, and we had not a single serious casualty caused by lance

stabs. The shorter cold steel arms are, the more secure and deadly. French cuirassier and

dragoon swords are definitely too long, and maybe even our own sabres are."

(There are several problems with this story. At Dennewitz was present only the 2nd Uhlan Regiment, the 4th Regiment was with Dabrowski's corps.

The single unit (2nd Uhlans) faced not only the Prussian hussars but also infantry.

George Nafziger wrote in his "Napoleon's Dresden Campaign" (p 260) "...the Polish cavalry

operating with Bertrand's IV Corps threw itself through the skirmish line and attacked the

formed infantry behind them. The Prussian 4th Reserve Infantry Regiment formed square, as

did three battalions of 3rd East Prussian Landwehr Regiment. The Poles then passed on and

were engaged by Tauentzien's cavalry... The 1st Leib Hussar Regiment also joined the attack.

The Poles were crushed, losing 9 officers and 93 men..."

Thus the casualties were inflicted not only by the hussars but also by 6 battalions of infatry

and by Tauentzien's cavalry. Ney sent orders to the Westphalian Cavalry Brigade to support the Poles but the Westphalians refused. Furious Ney sent the colonel of the

Westphalians to Napoleon after "ripping off his epaulettes."

Lancers vs Cuirassiers.

Lance's point couldn't penetrate the armor.

Some of the Polish veterans however

used lances as battering rams

- striking at tops of opponents' helmets

with force.

When in 1809 Napoleon's horse carabiniers suffered heavy

casualties from Austrian uhlans he gave them armor. Lance's point couldn't penetrate the armor.

When in 1809 Napoleon's horse carabiniers suffered heavy

casualties from Austrian uhlans he gave them armor. Lance's point couldn't penetrate the armor.

In 1812 at Shevardino, the lancers fought with cuirassiers. Thirion writes: "General Nansouty orders the Red Lancers of Hamburg

to charge the Russian cavalry and throw it back. This regiment flew to the attack, delivered its charge and fell on the enemy

with felled lances, aimed at the body. The Russian cavalry received the shock without budging, and in the same moment

as the lance heads touched the enemy's chests the regiment about-faced and came back towards us as if in its

turn had been charged. We, the [French] 2nd and 3rd Cuirassiers, thought this is a poor show, and moved briskly forward to support them

and repulse the enemy cavalry." Britten-Austin add "... nothing can induce them [Hamburg lancers]

to launch a second attack."

In 1813 in the Battle of Leipzig the Austrian Sommariva Cuirassiers went into action against Berkheim's French lancers.

The lancers broke and fled closely followed by the Austrians. A Saxon officer recalled the event as follow: "When we [Saxon cuirassiers] reached Berckheim, his men were mixed up with the enemy

in individual squadrons, so that there were Austrian units to the north of the French lancers. We Saxons had only just come up wwhen Berckheim rallied his men to face

the ever-increasing enemy pressure. But they could not stand even though Berckheim - bareheaded, as his hat

had been knocked off - threw himself into the thick of the melee.

He was also swept back in the flood of fugitives ... Despite this chaos, we stood fast and hacked away

at the Austrians. Shortly before they charged us, the Austrians had shouted to us to come over to them; we ignored them.

However, we were overpowered and broken. The chase now went on at speed, friend and foe all mixed up together, racing over the plain."

Antoni Rozwadowski of Polish 8th Uhlans

described fighting with Russian cavalry at Borodino: “On that day (Sep 5th)

the 6th Uhlans formed the first line, and we the 8th were formed in echelon” when

Russian dragoons attacked. According to Rozwadowski the soil was dry and a huge,

thick cloud of dust made his 8th invisible to the enemy. The Russians continued

their advance against the 6th before the 8th attacked the left flank of the

dragoons. The enemy fled in disorder.

After this action the 8th and 6th Uhlans moved to a new position behind a wood.

The regiments were now formed in column, one after another and only the brigades

stood in echelon. Soon the uhlans noticed Russian cavalry again charging against

them. At a long distance the enemy looked similar to the dragoons just recently

defeated and the Poles rushed forward certain of victory. When both sides were

closer the uhlans realized that these “dragoons” were cuirassiers and the 6th fled

toward the 8th. The 8th became disordered and both regiments fled and broke the

Prussian hussars who stood in the rear. Only the next cavalry brigade who stood

in echelon to the Poles counterattacked and threw the Russian cuirassiers back.

(Rozwadowski Antoni - “Memoir” Biblioteka Zakladu Ossolinskich, rekopis 7994)

Only few lancers were able to deal with armored cavalry.

In 1813 at Leipzig, Polish 3rd, 6th and 8th Uhlan Regiment, mostly veterans, didn't shy

away from the cuirassiers. Near Auenhain Sheep-farm the three regiments charged numerous times against six Austrian and two Russian cuirassier

regiments. The Poles pointed their lances at cuirassiers' faces, necks and groins.

(According to P. Haythornthwaite "lance can be aimed at a target with greater accuracy

than a sword.") They also used lances as battering rams - striking at tops of opponents'

helmets with force.

Lancers vs Infantry.

"a cavalry charge against infantry in square

would be thrown back 99 times out of 100."

- Mark Adkin

According to Mark Adkin "a cavalry charge against infantry in square would be thrown back

99 times out of 100." Simple mathematics was against the cavalry when they attacked a square.

An average strength battalion with 600 men formed a square 3 ranks deep, this meant that on

one side were some 150 soldiers, all of whom could fire and contributed bayonets to the hedge.

They covered a frontage of about 25 m (50 men x 0.5 m). The most cavalrymen that the enemy

could bring to face them were 50 in 2 ranks (25 men x 1 m). But only the men in first

rank could attack at a time, some 6 muskets + bayonets confronted

a single lance or saber.

According to Mark Adkin "a cavalry charge against infantry in square would be thrown back

99 times out of 100." Simple mathematics was against the cavalry when they attacked a square.

An average strength battalion with 600 men formed a square 3 ranks deep, this meant that on

one side were some 150 soldiers, all of whom could fire and contributed bayonets to the hedge.

They covered a frontage of about 25 m (50 men x 0.5 m). The most cavalrymen that the enemy

could bring to face them were 50 in 2 ranks (25 men x 1 m). But only the men in first

rank could attack at a time, some 6 muskets + bayonets confronted

a single lance or saber.

The man with saber could not strike the infantrymen behind the

bayonets - he did not have the reach.

A lancer had a better chance although he was still

outnumbered by 6 to 1. Either the lancer or his horse was far more likely to be spiked

than he was to inflict any damage at all."

In 1812 at Borodino and in 1813 at Leipzig masses of lancers and uhlans were

unable to break a single square. However, if the infantry was not in square formation the chances increased for the lancers.

In 1811 at Albuera one regiment of Polish uhlans and one of French hussars, demolished the

entire British brigade, captured several Colors, several cannons, and hundreds of prisoners.

I know only few cases where the lancers broke infantry formed in square.

In 1813 at Dresden the Austrian square repulsed French cuirassiers but surrendered without

a fight to lancers. Another square also repulsed cuirassiers but broke when 50 French

lancers attacked them. The frustrated cuirassiers joined the lancers and together finished

off the enemy.

In 1813 at Katzbach the lancers were called after the 23rd Chasseurs was repulsed. The lancers came and broke the square, inflicting heavy

casualties on the Prussians.

In 1813 at Dennewitz one squadron of Polish 2nd Uhlan Regiment

attacked Prussian battalion of 3rd Reserve Infantry Regiment. The infantry was formed in a

column with skirmishers as its screen. The uhlans routed the skirmishers killing several

and attacked the column. The Prussians were "savagely handled". The 2nd Uhlans also broke 2 other squadrons at

Dennewitz.

|

Videttes >

Videttes >

In an economic sense, the heavy cavalry signified an enormous investment by

its supporting state. The armor and the large horses were expensive. Heavy cavalry was

composed of large men sometimes in defensive armour (French carabinier was above 179 cm tall, cuirassier 173 cm, dragoon 170 cm, while the

light chasseur and hussar only 160 cm). The heavies were mounted on big and strong horses,

but these were deficient in speed and endurance. These mounts were more sensitive to

quantity and quality of food, and to weather. For all these reasons they were not made to

pursue the enemy, frequent skirmishing or even to escort a convoy.

In an economic sense, the heavy cavalry signified an enormous investment by

its supporting state. The armor and the large horses were expensive. Heavy cavalry was

composed of large men sometimes in defensive armour (French carabinier was above 179 cm tall, cuirassier 173 cm, dragoon 170 cm, while the

light chasseur and hussar only 160 cm). The heavies were mounted on big and strong horses,

but these were deficient in speed and endurance. These mounts were more sensitive to

quantity and quality of food, and to weather. For all these reasons they were not made to

pursue the enemy, frequent skirmishing or even to escort a convoy.

Their main role was a shock action on the battlefield. Cohesion and control were the goals to impose upon the enemy, and not to make individual combats.

They charged in large, close formation, exchanging much of the mobility advantage for a

massive, irresistible charge.

Their main role was a shock action on the battlefield. Cohesion and control were the goals to impose upon the enemy, and not to make individual combats.

They charged in large, close formation, exchanging much of the mobility advantage for a

massive, irresistible charge.

In 1815 at

In 1815 at  The light cavalry consisted of uhlans/lancers, light dragoons/chevuxlegeres/chasseurs, and

hussars. Light cavalry was called upon to watch over the safety of the army, and they were constantly

hovering in advance, and on the flanks to prevent all possibility of surprise on the part of

the enemy. They were also designed for foraging and pursuit. On ocassion they could be used

for shock action.

The light cavalry consisted of uhlans/lancers, light dragoons/chevuxlegeres/chasseurs, and

hussars. Light cavalry was called upon to watch over the safety of the army, and they were constantly

hovering in advance, and on the flanks to prevent all possibility of surprise on the part of

the enemy. They were also designed for foraging and pursuit. On ocassion they could be used

for shock action.

The light cavalry, and especially the hussars, were generally less disciplined than the

heavies. The hussars were the most known and popular of all the light cavalrymen. The first hussars

were formed in Hungary, and during the napoleonic wars almost every army had its own hussars.

There were men who had been bad actors in the non-combat period, who as consistently

became lions on the battlefield, with all the virtues of sustained aggressivenness.

The light cavalry, and especially the hussars, were generally less disciplined than the

heavies. The hussars were the most known and popular of all the light cavalrymen. The first hussars

were formed in Hungary, and during the napoleonic wars almost every army had its own hussars.

There were men who had been bad actors in the non-combat period, who as consistently

became lions on the battlefield, with all the virtues of sustained aggressivenness.

Map: horse breeding regions.

In white color horses for light and medium cavalry,

in yellow for medium and heavy cavalry (borders from 2000)

Map: horse breeding regions.

In white color horses for light and medium cavalry,

in yellow for medium and heavy cavalry (borders from 2000)

Photo: French light cavalry sabre from Military Heritage

Photo: French light cavalry sabre from Military Heritage

Photo: French cuirassier sabre from Military Heritage

Photo: French cuirassier sabre from Military Heritage  Photo: Prussian light cavalry sabre from MilitaryHeritage

Photo: Prussian light cavalry sabre from MilitaryHeritage  Photo: British heavy cavalry sabre from Military Heritage

Photo: British heavy cavalry sabre from Military Heritage  On picture: Russian lances of the Napoleonic Wars, by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

The length of Russian lance was between 280 and 290 cm. It was modeled on the Polish lance.

The pennant was called horonzhevka from Polish horagiewka.

On picture: Russian lances of the Napoleonic Wars, by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

The length of Russian lance was between 280 and 290 cm. It was modeled on the Polish lance.

The pennant was called horonzhevka from Polish horagiewka.

On photo: French cavalry carbine from Military Heritage

On photo: French cavalry carbine from Military Heritage  On photo: French cavalry pistol from Military Heritage

On photo: French cavalry pistol from Military Heritage  Photo: armor of French horse carabinier (left) and French cuirassier (right).

Photo: armor of French horse carabinier (left) and French cuirassier (right).

French officer de Brack: "The rolled coat may be considered a defensive weapon. The habit of rolling it, and crossing it

over the chest, in view of an engagement, has three advantages: first, it clears the opening of the pistol holster; second,

it allows the bridle hand to be carried nearer to the horse's neck, which facilitates the control of the horse; and, third, it

protects the trooper.

French officer de Brack: "The rolled coat may be considered a defensive weapon. The habit of rolling it, and crossing it

over the chest, in view of an engagement, has three advantages: first, it clears the opening of the pistol holster; second,

it allows the bridle hand to be carried nearer to the horse's neck, which facilitates the control of the horse; and, third, it

protects the trooper.  Most blows were directed against opponent's head, right forearm and right hand.

For this reason these areas required protection.

Most blows were directed against opponent's head, right forearm and right hand.

For this reason these areas required protection.

One could deliver an effective thrust also with the shorter curved saber. According to Charles Parquin, Prince Louis

of Prussia, the king's nephew was killed by a thrust to his chest delivered by French hussar

Guindey. "Brushing aside Guindey's weapon, the prince struck Guindey a blow across the face

with his saber. He was about the strike a second time when Guindey countered and ran him

through the chest. Killed instantly the prince fell from his horse."

One could deliver an effective thrust also with the shorter curved saber. According to Charles Parquin, Prince Louis

of Prussia, the king's nephew was killed by a thrust to his chest delivered by French hussar

Guindey. "Brushing aside Guindey's weapon, the prince struck Guindey a blow across the face

with his saber. He was about the strike a second time when Guindey countered and ran him

through the chest. Killed instantly the prince fell from his horse."

The basic tactical unit in cavalry was squadron.

Napoleon said that "squadron will be to the cavalry what the battalion is for infantry."

The cavalry strength in battle was expressed in the number of squadrons instead of regiments

or divisions. The strength of squadron varied between 75 and 250 men. In 1809 at Wagram were

209 squadrons of French cavalry with an average of 139 men per squadron.

The basic tactical unit in cavalry was squadron.

Napoleon said that "squadron will be to the cavalry what the battalion is for infantry."

The cavalry strength in battle was expressed in the number of squadrons instead of regiments

or divisions. The strength of squadron varied between 75 and 250 men. In 1809 at Wagram were

209 squadrons of French cavalry with an average of 139 men per squadron.

Horses speed varies with their stride length, body build, and other factors.

The so-called "natural" gaits are walk, trot, canter, and gallop (in increasing order of speed).

Canter is smoother than trot. Walk is slow. Trot is more bouncy and is descibed as being two-time,

this is because each stride taken by the horse has two beats.

Horses speed varies with their stride length, body build, and other factors.

The so-called "natural" gaits are walk, trot, canter, and gallop (in increasing order of speed).

Canter is smoother than trot. Walk is slow. Trot is more bouncy and is descibed as being two-time,

this is because each stride taken by the horse has two beats.

The echelon formation was easier formation to manoeuvre, and the direction of the advance

could be swiftly changed. There were echelons by squadrons, by regiments, by brigades

and even by entire divisions.

The echelon formation was easier formation to manoeuvre, and the direction of the advance

could be swiftly changed. There were echelons by squadrons, by regiments, by brigades

and even by entire divisions.

The width of cavalry column varied between half-squadron, through squadron (most common)

to multi-squadron.

The width of cavalry column varied between half-squadron, through squadron (most common)

to multi-squadron.

Looked at from the front such a line, even advancing at a trot, presented a military

spectactle that had few equals. This formation ensured the greatest number of sabres or

lances were brought to bear on the enemy and the wide frontage helped in outflanking the enemy.

But the longer the line the more difficult it was to control and it should be as short as possible, so as to reach an enemy in good order, and without fatiguing the horses.

Looked at from the front such a line, even advancing at a trot, presented a military

spectactle that had few equals. This formation ensured the greatest number of sabres or

lances were brought to bear on the enemy and the wide frontage helped in outflanking the enemy.

But the longer the line the more difficult it was to control and it should be as short as possible, so as to reach an enemy in good order, and without fatiguing the horses.

Fig. 109: French Cavalry Regiment of 4 squadrons forming line from column.

[Source: Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets."]

Fig. 109: French Cavalry Regiment of 4 squadrons forming line from column.

[Source: Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets."] Fig. 123: Prussian Cavalry Regiment of 4 squadrons forming column by squadron.

[Source: Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets"]

Fig. 123: Prussian Cavalry Regiment of 4 squadrons forming column by squadron.

[Source: Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets"] With few exceptions, the Hollywood version of battle evokes images of the every man,

fighting to death without asking any questions. The "good guy" always win over the "bad guy".

The movies obscure the reality of battle that would put the "heroes" label in doubt.

With few exceptions, the Hollywood version of battle evokes images of the every man,

fighting to death without asking any questions. The "good guy" always win over the "bad guy".

The movies obscure the reality of battle that would put the "heroes" label in doubt.

Geography and tradition played role. Generally the more to the east the more common

was the use of curved saber (instead of straight one). The men of steppes and plateaus of

Eastern Europe and Asia spent their their lives on horses. Their mounts were smaller

and more agile. The eastern cavalry however lacked discipline and firepower.

Their battles were short and chaotic affairs where man fought against man or two.

The situation in combat changed very quickly and required lighter and shorter weapons for

quick blows or parries to the left, right or rear. The greater curvature enabled to deliver

a cut or slash through the padded protection of the adversary or take his head off with little

effort.

Geography and tradition played role. Generally the more to the east the more common

was the use of curved saber (instead of straight one). The men of steppes and plateaus of

Eastern Europe and Asia spent their their lives on horses. Their mounts were smaller

and more agile. The eastern cavalry however lacked discipline and firepower.

Their battles were short and chaotic affairs where man fought against man or two.

The situation in combat changed very quickly and required lighter and shorter weapons for

quick blows or parries to the left, right or rear. The greater curvature enabled to deliver

a cut or slash through the padded protection of the adversary or take his head off with little

effort.

Napoleon described this: "Two Mamelukes held 3 Frenchmen; but 100 French

cavalry did not fear the same number of Mamelukes; ... 1.000 French beat 1.500 Mamelukes. Such was the influence of tactics, order

and maneuver."

Napoleon described this: "Two Mamelukes held 3 Frenchmen; but 100 French

cavalry did not fear the same number of Mamelukes; ... 1.000 French beat 1.500 Mamelukes. Such was the influence of tactics, order

and maneuver."

Good cavalry usage entailed sending out cavalry videttes to screen an army's advance

and gathering intelligence.

The videttes furnished the alert eyes that screened the army from enemy observation.

Lack of videttes has sometimes led to great and humiliating surprises.

Without videttes an army or corps commander would be at the mercy of his foe

as the videttes were the first line of defense against a sudden enemy move,

the outermost ring in a series of human alarm bells.

Good cavalry usage entailed sending out cavalry videttes to screen an army's advance

and gathering intelligence.

The videttes furnished the alert eyes that screened the army from enemy observation.

Lack of videttes has sometimes led to great and humiliating surprises.

Without videttes an army or corps commander would be at the mercy of his foe

as the videttes were the first line of defense against a sudden enemy move,

the outermost ring in a series of human alarm bells.

Usually the horse skirmishers advanced in front of their parent squadron or regiment,

fired and moved about a bit to reduce their target ability. They were able to

prevent the enemy's troops from hiding behind trees and broken ground, looked for ambushes,

or simply observed the enemy’s movements or intent. It was also quite good way

to test enemy resolve at a specific point and gather information about his position

as well.

Usually the horse skirmishers advanced in front of their parent squadron or regiment,

fired and moved about a bit to reduce their target ability. They were able to

prevent the enemy's troops from hiding behind trees and broken ground, looked for ambushes,

or simply observed the enemy’s movements or intent. It was also quite good way

to test enemy resolve at a specific point and gather information about his position

as well.

The carbine fire could be delivered in two ways: individually or by squadrons.

Firing by squadron was not an easy thing. The horses never stood

still in noisy environment making any aiming from the saddle close to impossible.

Some horses came as replacement during campaign and were not accustomed to battlefield

conditions. They easily got upset by the noise and discharges. In such situation the

men were preoccupied with controling the horse rather than with loading and firing.

Even worse, sometimes the burning powder would pepper over the horses throwing them into

panick !

The carbine fire could be delivered in two ways: individually or by squadrons.

Firing by squadron was not an easy thing. The horses never stood

still in noisy environment making any aiming from the saddle close to impossible.

Some horses came as replacement during campaign and were not accustomed to battlefield

conditions. They easily got upset by the noise and discharges. In such situation the

men were preoccupied with controling the horse rather than with loading and firing.

Even worse, sometimes the burning powder would pepper over the horses throwing them into

panick !

The column of French dragoons halted and stood motionless like a stonewall [kak kamennaia stiena]

waiting for the Russians. The dragoons from the second rank grabbed their muskets and began firing while these in the first

rank drew sabers and waited. The charging uhlans first slowed down and then halted. The French sounded massive

“En avant ! Vive l’Empereur!” and advanced forward en masse. The uhlans and Cossacks gave way before the

sheer weight of the column. Their retreat was covered by flankers who opened fire on the pursuing dragoons.

The column of French dragoons halted and stood motionless like a stonewall [kak kamennaia stiena]

waiting for the Russians. The dragoons from the second rank grabbed their muskets and began firing while these in the first

rank drew sabers and waited. The charging uhlans first slowed down and then halted. The French sounded massive

“En avant ! Vive l’Empereur!” and advanced forward en masse. The uhlans and Cossacks gave way before the

sheer weight of the column. Their retreat was covered by flankers who opened fire on the pursuing dragoons.

"We continued at a walk for another 300 paces, and I instructed both squadrons to go hell for leather as soon as I sounded the

charge. They were not lower their lances, however, but should point them at the enemy's

faces. ... We were perhaps 200 paces away when I ordered, 'Charge !' and in the blinking of an eye we were upon them. ...

The melee lasted but a few seconds. From the moment we struck, the enemy fell into confusion and began to retreat,

even including the uhlans who had no foe to their front. I did not see how many men fell because I had passed

through their line so quickly. My squadrons had themselves become disordered and individuals were chasing after those of the enemy whose horses were weakest, and ordering them

to dismount."

"We continued at a walk for another 300 paces, and I instructed both squadrons to go hell for leather as soon as I sounded the

charge. They were not lower their lances, however, but should point them at the enemy's

faces. ... We were perhaps 200 paces away when I ordered, 'Charge !' and in the blinking of an eye we were upon them. ...

The melee lasted but a few seconds. From the moment we struck, the enemy fell into confusion and began to retreat,

even including the uhlans who had no foe to their front. I did not see how many men fell because I had passed

through their line so quickly. My squadrons had themselves become disordered and individuals were chasing after those of the enemy whose horses were weakest, and ordering them

to dismount."

During the decades before Napoleonic Wars only the dragoons were trained in infantry and

cavalry duties. General Jomini wrote: "Opinions will be always divided as to those

amphibious animals called dragoons. It is certainly an advantage to have several battalions

of mounted infantry, who can anticipate an enemy at a defile, or scour a wood; but to make

cavalry out of foot soldiers is very difficult. ...

During the decades before Napoleonic Wars only the dragoons were trained in infantry and

cavalry duties. General Jomini wrote: "Opinions will be always divided as to those

amphibious animals called dragoons. It is certainly an advantage to have several battalions

of mounted infantry, who can anticipate an enemy at a defile, or scour a wood; but to make

cavalry out of foot soldiers is very difficult. ...

It has been said that the greatest

inconvenience resulting from the use of dragoons consists in the fact of being obliged at one

moment to make them believe infantry squares cannot resist their charges, and the next moment

that a foot soldier is superior to any horseman... But it cannot be denied, however, that

great advantages might result to the general who could rapidly move up 10,000 infantrymen

on horseback to a decisive point ..."

It has been said that the greatest

inconvenience resulting from the use of dragoons consists in the fact of being obliged at one

moment to make them believe infantry squares cannot resist their charges, and the next moment

that a foot soldier is superior to any horseman... But it cannot be denied, however, that

great advantages might result to the general who could rapidly move up 10,000 infantrymen

on horseback to a decisive point ..."

The cavalry charge was one of the most eye-catching sights.

The dust thrown by charging cavalry was so thick and rose so high that it

totally obscured the view. (In 1757 at Prague the movement of Prussian cavalry threw

up great clouds which made the day seem "like the end of the world." One of the Prussians

wrote: "the dust had prevented me from seeing more than four paces.")

The cavalry charge was one of the most eye-catching sights.

The dust thrown by charging cavalry was so thick and rose so high that it

totally obscured the view. (In 1757 at Prague the movement of Prussian cavalry threw

up great clouds which made the day seem "like the end of the world." One of the Prussians

wrote: "the dust had prevented me from seeing more than four paces.")

The moral effect of a mass charging in good order was of the greatest influence.

Brave but undisciplined cavalry would be most often defeated by disciplined troops.

"We have often seen fanatic eastern people implicitly believing that death in battle means

a happy and glorious resurection. Despite being better mounted they give way before

discipline."

The moral effect of a mass charging in good order was of the greatest influence.

Brave but undisciplined cavalry would be most often defeated by disciplined troops.

"We have often seen fanatic eastern people implicitly believing that death in battle means

a happy and glorious resurection. Despite being better mounted they give way before

discipline."

If both sides were of equal morale then the horsemen would pass through each other's

formation and come out on the other side. Sometimes they would continue forward until were

overthrown by the second line of enemy's cavalry.

If both sides were of equal morale then the horsemen would pass through each other's

formation and come out on the other side. Sometimes they would continue forward until were

overthrown by the second line of enemy's cavalry.

During battle some cavalry regiments were kept in reserve,

while others made numerous charges.

In 1814 in the Battle of Craonne, Russian hussar division was so involved in fighting that all

their generals were either wounded, injured or killed. The Pavlograd Hussars

conducted 8 charges and despite the exhaustion of horses and men

they formed the rear guard of the retreating infantry.

They paid the heaviest price for their heroics - this is said that out of 900 men

half were killed, wounded and injured.

During battle some cavalry regiments were kept in reserve,

while others made numerous charges.

In 1814 in the Battle of Craonne, Russian hussar division was so involved in fighting that all

their generals were either wounded, injured or killed. The Pavlograd Hussars

conducted 8 charges and despite the exhaustion of horses and men

they formed the rear guard of the retreating infantry.

They paid the heaviest price for their heroics - this is said that out of 900 men

half were killed, wounded and injured.

"But shortly I saw a second enemy line approaching, all of them uhlans. I stopped my horse, and had only begun to restore order

to the ranks when this line began a charge. I was obliged to reform as best I could, 'Forward ! March !' otherwise they

would have caught us stationary, which you should never let the enemy do. ... As they charged, the Russian uhlans lost some of their dressing, but they still came on and broke into our line.

They outnumbered us, and we should certainly have been beaten if Jerzmanowski had not come up with

his two squadrons. He was the very best field officer in the regiment ... and with a fine,

cool judgement. At just the right moment he struck the enemy from our left flank, having come up close at a walk to save energy for his charge.

"But shortly I saw a second enemy line approaching, all of them uhlans. I stopped my horse, and had only begun to restore order

to the ranks when this line began a charge. I was obliged to reform as best I could, 'Forward ! March !' otherwise they

would have caught us stationary, which you should never let the enemy do. ... As they charged, the Russian uhlans lost some of their dressing, but they still came on and broke into our line.

They outnumbered us, and we should certainly have been beaten if Jerzmanowski had not come up with

his two squadrons. He was the very best field officer in the regiment ... and with a fine,

cool judgement. At just the right moment he struck the enemy from our left flank, having come up close at a walk to save energy for his charge.

"Then another regiment regiment of Russian uhlans appeared ... and advanced toward us in line.

But when it was still 500 paces away it broke into a gallop.

Lefebvre-Desnouettes ... again wanted us to counter-charge.

Jerzmanowski, who knew the general very well, told him there was no point in charging, as the enemy

had begun to gallop far too soon; they would soon lose formation and would never reach us.

Sure enough, their line shortly broke up, a few dozen pulled ahead and the majority began to

slow down. Nobody came any closer to us than 100 paces. ... General ordered two platoons to form skirmish order and go out to meet them.

They brought back half a dozen or more of the slowest horsemen. We discovered they weren't lances, but regular Ukrainian Cossacks.

... The Cossacks had retreated and were reforming a very long way away from us.

This proved them to be very young recruits, whose officers were probably no better.

... Now General Walther appeared, and after complimenting us on our charge he ordered us to march off by platoons to the left and advance up the slope ... "

"Then another regiment regiment of Russian uhlans appeared ... and advanced toward us in line.

But when it was still 500 paces away it broke into a gallop.

Lefebvre-Desnouettes ... again wanted us to counter-charge.

Jerzmanowski, who knew the general very well, told him there was no point in charging, as the enemy

had begun to gallop far too soon; they would soon lose formation and would never reach us.

Sure enough, their line shortly broke up, a few dozen pulled ahead and the majority began to

slow down. Nobody came any closer to us than 100 paces. ... General ordered two platoons to form skirmish order and go out to meet them.

They brought back half a dozen or more of the slowest horsemen. We discovered they weren't lances, but regular Ukrainian Cossacks.

... The Cossacks had retreated and were reforming a very long way away from us.

This proved them to be very young recruits, whose officers were probably no better.

... Now General Walther appeared, and after complimenting us on our charge he ordered us to march off by platoons to the left and advance up the slope ... "

The Guard Lancer Regiment then marched to Haynau and camped there until Napoleon arrived.

Napoleon ordered the Cavalry of the Imperial Guard circle the town of Lignica (?) in order to catch any enemy that might still be retreating.

Chlapowski: "As soon as my two squadrons had crossed, I led them rapidly out of the village ...

When we arrived in the open again I saw four squadrons standing in line.

So I turned my line to face them and just as we did so, they began to advance and their trumpeters sounded the charge. I advanced to meet them.

... They stopped, turned right around, and began to retreat just as we fell upon them.

As might be expected, they routed.

The Guard Lancer Regiment then marched to Haynau and camped there until Napoleon arrived.

Napoleon ordered the Cavalry of the Imperial Guard circle the town of Lignica (?) in order to catch any enemy that might still be retreating.

Chlapowski: "As soon as my two squadrons had crossed, I led them rapidly out of the village ...

When we arrived in the open again I saw four squadrons standing in line.

So I turned my line to face them and just as we did so, they began to advance and their trumpeters sounded the charge. I advanced to meet them.

... They stopped, turned right around, and began to retreat just as we fell upon them.

As might be expected, they routed.

Picture: French cuirassiers and Russian Life Guard

(heavy cavalry) in melee in 1807. Picture by Viktor Mazurovsky, Russia.

Picture: French cuirassiers and Russian Life Guard

(heavy cavalry) in melee in 1807. Picture by Viktor Mazurovsky, Russia.

When hostile cavalries meet each other, there is usually but small loss on either side.

Only in few cavalry battles the casualties were heavy.

When hostile cavalries meet each other, there is usually but small loss on either side.

Only in few cavalry battles the casualties were heavy.

Generally the Frenchman was an inferior horseman and swordsman as comparing to the British,

Prussian and Austrian cavalryman. So why did the French cavalry won in so many engagements ?

One factor was certainly their superior organization, at high levels, to most of their

opponents. The French command structure and organization made it more likely that a

French cavalry had reserves available, and the ability to direct them to exploit a break in

the enemy line or plug a gap in their own, or counterattack the victorious enemy.

Their discipline and tactics of using larger formations impressed even the enemies of France.

Generally the Frenchman was an inferior horseman and swordsman as comparing to the British,

Prussian and Austrian cavalryman. So why did the French cavalry won in so many engagements ?

One factor was certainly their superior organization, at high levels, to most of their

opponents. The French command structure and organization made it more likely that a

French cavalry had reserves available, and the ability to direct them to exploit a break in

the enemy line or plug a gap in their own, or counterattack the victorious enemy.

Their discipline and tactics of using larger formations impressed even the enemies of France.

The Poles used to say that every commander loved the lancers for their looks,

but not every man wished to carry the heavy weapon for all year long.

The lance was traditional weapon of the Poles. First the Polish legendary Winged Knights

(husaria) used it with great success against their enemies. Husaria's lance was

approx. 5 m long. They attacked frontally smashing everything on their way.

The times changed and the Winged Knights were replaced with uhlans (ulani) - armed with

2.5 m long lances. During march the weight of the lance bore down on the stirrup, where its lower

end fitted into a small 'bucket'; carried on the march slanting back from a small sling around

the rider's arm.

The Poles used to say that every commander loved the lancers for their looks,

but not every man wished to carry the heavy weapon for all year long.

The lance was traditional weapon of the Poles. First the Polish legendary Winged Knights

(husaria) used it with great success against their enemies. Husaria's lance was

approx. 5 m long. They attacked frontally smashing everything on their way.

The times changed and the Winged Knights were replaced with uhlans (ulani) - armed with

2.5 m long lances. During march the weight of the lance bore down on the stirrup, where its lower

end fitted into a small 'bucket'; carried on the march slanting back from a small sling around

the rider's arm.

In 1809 in Vienna, Polish NCO Jordan of Guard Lighthorse, called upon dragoons of Napoleon's

Old Guard, to "fight" him. Two battle-hardened veterans

stepped out, he unhorsed both. (see picture -->)

In 1809 in Vienna, Polish NCO Jordan of Guard Lighthorse, called upon dragoons of Napoleon's

Old Guard, to "fight" him. Two battle-hardened veterans

stepped out, he unhorsed both. (see picture -->)

Right: the legendary charge of British lancers at Balaklava, October 25th 1854.

Their uniforms closely resembled the dress of the Polish Vistula uhlans.

Right: the legendary charge of British lancers at Balaklava, October 25th 1854.

Their uniforms closely resembled the dress of the Polish Vistula uhlans. The story of heroic Polish uhlans attacking German tanks during WW2 is a myth.

On Sept 1st 1939 at Krojanty part of Polish 18th Uhlan Regiment successfully charged German infantry battalion resting near woods

but then got under heavy machine gun fire and withdrew. According to

General Heinz Guderian this charge impressed the Germans and caused a wide spread panic among the

staff and infantry. The same day the German war correspondents were brought to the

battlefield together with two journalists from Italy. They were shown the battlefield, the corpses of uhlans and their horses, as well as German tanks that arrived to the

place after the battle. One of the Italian correspondents sent home an article, in which he

described the bravery of the uhlans, who charged German tanks with sabres and lances.

Although such a charge did not happen and there were no tanks used during the combat, the myth

was used by German propaganda during the war. One film even showed a cavalry charge on tanks, with Polish uhlans (in German helmets and

uniforms) using their lances against tanks.

The story of heroic Polish uhlans attacking German tanks during WW2 is a myth.

On Sept 1st 1939 at Krojanty part of Polish 18th Uhlan Regiment successfully charged German infantry battalion resting near woods

but then got under heavy machine gun fire and withdrew. According to

General Heinz Guderian this charge impressed the Germans and caused a wide spread panic among the

staff and infantry. The same day the German war correspondents were brought to the

battlefield together with two journalists from Italy. They were shown the battlefield, the corpses of uhlans and their horses, as well as German tanks that arrived to the

place after the battle. One of the Italian correspondents sent home an article, in which he

described the bravery of the uhlans, who charged German tanks with sabres and lances.

Although such a charge did not happen and there were no tanks used during the combat, the myth

was used by German propaganda during the war. One film even showed a cavalry charge on tanks, with Polish uhlans (in German helmets and

uniforms) using their lances against tanks.

Left: German SS Geyer Cavalry Division in 1942.

The Division saw action on the Eastern Front, in areas such as Briansk, Viazma and the mighty

Left: German SS Geyer Cavalry Division in 1942.

The Division saw action on the Eastern Front, in areas such as Briansk, Viazma and the mighty

Lance was the most dangerous in the first contact during line-vs-line combats.

The long weapon allowed cavalrymen to wound or kill an enemy armed with shorter weapon first.

Once the enemy had got past the point of the lance then the lancer was vulnerable.

General Jomini wrote that lance is the most aggressive weapon as one can simply outreach

every opponent.

Lance was the most dangerous in the first contact during line-vs-line combats.

The long weapon allowed cavalrymen to wound or kill an enemy armed with shorter weapon first.

Once the enemy had got past the point of the lance then the lancer was vulnerable.

General Jomini wrote that lance is the most aggressive weapon as one can simply outreach

every opponent.

Disadvantages of lance:

Disadvantages of lance: When in 1809 Napoleon's horse carabiniers suffered heavy

casualties from Austrian uhlans he gave them armor. Lance's point couldn't penetrate the armor.

When in 1809 Napoleon's horse carabiniers suffered heavy

casualties from Austrian uhlans he gave them armor. Lance's point couldn't penetrate the armor.

According to Mark Adkin "a cavalry charge against infantry in square would be thrown back

99 times out of 100." Simple mathematics was against the cavalry when they attacked a square.

An average strength battalion with 600 men formed a square 3 ranks deep, this meant that on

one side were some 150 soldiers, all of whom could fire and contributed bayonets to the hedge.

They covered a frontage of about 25 m (50 men x 0.5 m). The most cavalrymen that the enemy

could bring to face them were 50 in 2 ranks (25 men x 1 m). But only the men in first

rank could attack at a time, some 6 muskets + bayonets confronted

a single lance or saber.

According to Mark Adkin "a cavalry charge against infantry in square would be thrown back

99 times out of 100." Simple mathematics was against the cavalry when they attacked a square.

An average strength battalion with 600 men formed a square 3 ranks deep, this meant that on

one side were some 150 soldiers, all of whom could fire and contributed bayonets to the hedge.

They covered a frontage of about 25 m (50 men x 0.5 m). The most cavalrymen that the enemy

could bring to face them were 50 in 2 ranks (25 men x 1 m). But only the men in first

rank could attack at a time, some 6 muskets + bayonets confronted

a single lance or saber.

In 1813 in the Battle of Leipzig one regiment of Hungarian hussars advanced

against a massive column of French heavy cavalry, all covered in armor and mounted

on large horses. Rilliet of the French 1st Cuirassiers witnessed the encounter:

"We were in column of regiments. The 1st Horse Carabiniers were in front and General Sebastiani was to the right of the regiment: all at once a mass of

enemy cavalry, mainly Hungarian hussars, rode furiously down on the carabiniers.

'Bravo!' cried the general, laughing and waving the riding crop which was the only

weapon that he designed to use.

In 1813 in the Battle of Leipzig one regiment of Hungarian hussars advanced

against a massive column of French heavy cavalry, all covered in armor and mounted

on large horses. Rilliet of the French 1st Cuirassiers witnessed the encounter:

"We were in column of regiments. The 1st Horse Carabiniers were in front and General Sebastiani was to the right of the regiment: all at once a mass of

enemy cavalry, mainly Hungarian hussars, rode furiously down on the carabiniers.

'Bravo!' cried the general, laughing and waving the riding crop which was the only

weapon that he designed to use.

Milhaud was furious: "what will appear incredible and makes me indignant and afflicts me, is that a wretched

charge of 200 cossacks and 2 squadrons of hussars, pushed back by my right ..." Milhaud with

saber in hand, counterattacked with some success. But when 4 squadrons of hussars

emerged from Burkersdorf the dragoons made half-turn and fled in disorder. Milhaud was unable

to rally his dragoons until Uderwangen. Humiliated Milhaud added: "I would have liked to die

in the fray."

Milhaud was furious: "what will appear incredible and makes me indignant and afflicts me, is that a wretched

charge of 200 cossacks and 2 squadrons of hussars, pushed back by my right ..." Milhaud with

saber in hand, counterattacked with some success. But when 4 squadrons of hussars

emerged from Burkersdorf the dragoons made half-turn and fled in disorder. Milhaud was unable

to rally his dragoons until Uderwangen. Humiliated Milhaud added: "I would have liked to die

in the fray."