|

.

"We soon recognized that they were Poles

by their courage and by the way they

handled their lances."

(- Charles Parquin, French officer)

In 1812 the Polish cavalry

"showed a marked superiority

over the French" [cavalry].

(Riehn - "1812: Napoleon's Russian Campaign")

|

Polish Cavalry.

"We are here to drink French wine

and to live our lives so well

that Death will tremble to take us !"

- Polish uhlan

Picture: Polish uhlans, reenactors. Photo from

Polonia Militaris . (ext.link)

Picture: Polish uhlans, reenactors. Photo from

Polonia Militaris . (ext.link)

Poland required numerous and good quality light cavalry to defend its

long borders against the elusive and agile Cossacks and Turks. The Polish cavalry helped to

solidify the eastern wall of Europe for nearly two centuries.

Thereafter, these deeds have been commemorated through plaques, memorials, marches,

literature and the media.

According to American historian John Elting, the "Poles were acknowledged to be the finest lancers in Europe; Russia,

Prussia, and Austria recruited their lancer regiments from among the Polish subjects their

partitionings of the unhappy kingdom had given them. When France marched against all Europe,

Polish volunteers swarmed into its ranks."

(Elting - "Swords Around a Throne" 1997 p 241)

The French cavalry commanders (Marshal Murat, General Lasalle and others) enjoyed leading the Poles into combat.

In Ostrovno in 1812 "Murat ... darted forward,

placing himself in front of the 8th Polish Uhlan Regiment

He excited them with his words and actions, though they were

already enraged by the sight of the advancing Russians. ...

He had no intention of throwing himself with them into the

midst of a melee ... but the Poles were already crouched in the saddle.

The charging cavalry covered the width of the field completely

and pushed Murat before them. He could neither separate from them or stop."

(Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 116)

The Polish 10th Hussar Regiment was the first Napoleonic unit to enter Mocow in

1812. They were followed by Prussian uhlans, Wirtembergian chasseurs and Pajol's

French hussars and chasseurs.

The Poles were one of the very few who could challenge the Cossacks.

The Poles enjoyed successes but also suffered two defeats (Mir and Romanow) against these

bearded warriors.

According to Austrian officer A. Prokesch "The Cossack fears horsemen of no nation, except the

Turks. For the Polish lancers he has admiration, because these were capable to fight in closed, as well as in open order,

and because he had to cope with them almost all the time during the latest war.

The French, as long as they possessed cavalry, held back

their own in closed order and sent forward the Polish for

light duties. The German and French light cavalry are not feared by the Cossack.

He will not stand and oppose their formed attacks, and in open order he will surpass them

in manoeuvrability." (A. Prokesch - ‘Ueber den Kosaken, und dessen Brauchbarkeit im Felde’)

The Dutch lancers were too phlegmatic for this kind of warfare. (Britten-Austin)

At Hohenlinden "Pawlikowski, a 23-year old NCO of uhlans, noticed Austrian infantry in a copse. Accompanied by a French chasseur

named Gotebeuf, he charged the Austrians (...) After killing 2 officers with his lance

he took prisoner 1 officer and 57 men. General Decean, who met him leading the

prisoners, offered him a promotion to lieutenant, but Pawlikowski answered in broken

French: 'No know read, no know write, no be officer." (Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons" p 100)

"In 1808, fed up with Spanish sniping, the Lancers of the Vistula climbed down from their saddles and stormed an entrenched Spanish

camp near Saragossa ... During the first phase of the siege they charged a fortified city. They penetrated essentially right to

its center. Unsupported and alone the lancers had to charge back out."

(Elting - "Swords Around a Throne")

In 1811 at Albuera the Vistula uhlans demolished British infantry brigade,

captured several Colors and cannons, and took hundreds of prisoners. All French cavalry put together never captured so many

British colors and prisoners.

In 1813 at Dennewitz three squadrons of 2nd Uhlan attacked and broke three squares formed by the Prussian infantry of Tauentzien's corps.

One squadron of the 2nd Uhlan Regiment attacked Prussian battalion of 3rd Reserve Infantry

Regiment. The infantry was formed in a column with skirmishers as its screen. The uhlans routed the skirmishers killing several

and attacked the column. The Prussians were "savagely handled".

In 1813 at Leipzig, the 1st Chasseurs (armed with lances) broke one Austrian square of Bianchi's division

near the Auenhain sheep-farm, and one square of Russian Helfreich's 14th Division.

In 1813 in Saxony several squadrons of Russian Soumy Hussars and one squadron of Alexandria Hussars

led by the “bloodthirsty and gruesome Figner” marched at night through enemy’s line. They have captured many stragglers who otherwise would reveal their presence. They halted in a village and Figner ordered complete silence. Several marauders who ventured into the village were killed. Only one managed to escape and informed the French command. The Polish uhlans came and with battle cries pushed into the village. The hussars jumped out of their hiding places and a fighting erupted in the short and narrow streets.

Von Löwenstern wrote that many hussars were unsaddled and littered on the ground.

The others fled with the Poles hot on their heels. The flight was slowed down by a narrow

defilee and the Poles again got their lance into work. According to von Löwenstern

(pages 136-137) when they finally escaped they were happy for the next days not to see the

uhlans again and were able to catch their breath again.

(According to Löwenstern, Figner was killed later on at Reichenbach by drowning in a

river being surrounded by Polish cavalrymen.)

Antoni Rozwadowski from the Polish 8e Uhlans

described fighting with the Russian cavalry at Borodino: “On that day (Sep 5th) the 6e Uhlans formed the first line, and we the 8e were formed in echelon” when Russian dragoons attacked. According to Rozwadowski the soil was dry and a huge, thick cloud of dust made his 8e invisible to the enemy. The Russians continued their advance against the 6e before the 8e attacked the left flank of the dragoons. The enemy fled in disorder.

After this action the 8e and 6e Uhlans moved to a new position behind a wood. There the regiments were formed in column, one after another and only the brigades stood in echelon. Soon the uhlans noticed Russian cavalry again charging against them. At a long distance the enemy looked similar to the dragoons just recently defeated and the Poles rushed forward certain of victory. When both sides were closer the uhlans realized that these “dragoons” were cuirassiers and the 6e fled toward the 8e. The 8e was disorganized and both regiments fled and broke the Prussian hussars who stood in the rear. Only the next cavalry brigade who stood in echelon to the Poles counterattacked and threw the Russian cuirassiers back.

(Rozwadowski - “Memoir” Biblioteka Zakladu Ossolinskich, rekopis 7994)

In 1813 at Leipzig the 3rd, 6th and 8th Uhlan Regiment (mostly veterans) didn't shy

away from the cuirassiers. Near Auenhain Sheep-farm the three units charged numerous times against six Austrian and two Russian cuirassier

regiments. The Poles pointed their lances at cuirassiers' faces, necks and groins.

(According to P. Haythornthwaite "lance can be aimed at a target with greater accuracy

than a sword.") They also used lances as battering rams - striking at tops of opponents'

helmets with force.

In 1814 officer Skarzynski overwhelmed and ridden down by a flood of Cossacks,

wrenched an "especially heavy" lance from one of them and - wild with the outraged fury of

despair - spurred amuck down the road, bashing every Cossack skull that came within his reach.

Rallying and wedging in behind him, his Polish handful cleared the field.

The same day Napoleon made Skarzynski the Baron of the Empire.

In 1813 in Saxony, several squadrons of Russian Soumy

Hussars and one squadron of Alexandria Hussars led by the “bloodthirsty and gruesome Figner”

marched at night through enemy’s line. They have captured many stragglers who otherwise would

reveal their presence. They halted in a village and Figner ordered complete silence.

Several marauders who ventured into the village were killed. Only one managed to

escape and informed the French command.

The Polish uhlans came and with battle cries pushed into the village. The Russians jumped

out of their hiding places and a fighting erupted in the short and narrow streets.

Von Löwenstern wrote that many hussars were unsaddled and littered on the ground.

The others fled with the Poles hot on their heels. The flight was slowed down by a narrow

defilee and the Poles again got their lance into work. According to von Löwenstern

(pp 136-137) when they finally escaped they were happy for the next days not

to see the uhlans again and were able to catch their breath again.

Figner’s detachment then moved toward Königswartha (?). They attacked French 10th

Hussars. The French hussars wearing their sky blue dolmans didn’t expect the

enemy from this side and fled without resistence. The Russians chased them until

the line of enemy’s infantry and artillery. Musket volleys and canister halted

the pursuers.

Near Lauban they were attacked by Saxon hussars attacked them. Löwenstern’s friend

was taken prisoner. The Russians retreated through a village toward the positions

where stood the rest of Figner’s detachment. Group of Don Cossacks

(Karpov’s division) was ordered to attack the pursuing Saxons but showed little

zeal. Furious Figner rode to their officer and strucked him with horsewhip.

(According to Löwenstern, the commander of detachment, Figner, was killed at Reichenbach

by drowning in a river being surrounded by Polish cavalry.)

In 1812 in the Battle of Chirikovo the Polish cavalry "showed a marked superiority

over the French" cavalry. (Riehn - "1812: Napoleon's Russian Campaign")

On 29 September the Poles and French fought with the Russians led by Raievski and

Miloradovich.

Organization of Polish Cavalry.

Poland was the only country in Europe

which in some point had an army

with more cavalry regiments than infantry regiments.

Poland was an open, flat country bordering the steppes of Asia.

It always had a high ratio of cavalry, higher than any western European army.

General Jomini wrote: "As a general rule, it maybe stated that an army in an open country

should contain cavalry to the amount of 1/6 its whole strength; in mountainous countries

1/10 will suffice."

In Poland the ratio was even higher.

Actually Poland (Grand Duchy of Warsaw) was the only country in Europe which in some

point had an army with more cavalry regiments than

infantry regiments. In contrast Switzerland had almost no cavalry at all.

In the end of 1813 Napoleon entertained thoughts of completely disbanding Polish infantry

and organizing four uhlan and two Polish-Cossack regiments.

The Polish cavalry regiment consisted of staff and usually 3 (in 1806-1809) or 4 squadrons of two

companies each. The 4-squadron regiment was commanded by colonel, major, 2 chefs d'escadron

and 2 adjutanbts-majors. There were also standard-bearer and trumpet-major.

The Polish cavalry regiment consisted of staff and usually 3 (in 1806-1809) or 4 squadrons of two

companies each. The 4-squadron regiment was commanded by colonel, major, 2 chefs d'escadron

and 2 adjutanbts-majors. There were also standard-bearer and trumpet-major.

In 1810 the organization of company was as follow:

4 officers: captain, lieutenant and 2 sous-lieutenants

14 NCOs: sergeant-major, 4 sergeants, fourrier and 8 corporals

Others: blacksmith, 2 trumpeters and 79 privates

Total strength = 100 men (+ 2 enfants de troupe)

Cavalry regiments in November 1807:

- 1st Cavalry Regiment (653 men) - Colonel J.M.Dabrowski - 1st Cavalry Regiment (653 men) - Colonel J.M.Dabrowski

- 2nd Cavalry Regiment (571 men) - Colonel Kwasniewski - 2nd Cavalry Regiment (571 men) - Colonel Kwasniewski

- 3rd Cavalry Regiment (857 men) - Colonel Laczynski - 3rd Cavalry Regiment (857 men) - Colonel Laczynski

- 4th Cavalry Regiment (823 men) - Colonel Mecinski - 4th Cavalry Regiment (823 men) - Colonel Mecinski

- 5th Cavalry Regiment (943 men) - Colonel Turno - 5th Cavalry Regiment (943 men) - Colonel Turno

- 6th Cavalry Regiment (996 men) - Colonel Dziewanowski - 6th Cavalry Regiment (996 men) - Colonel Dziewanowski

The Poles numbered their cavalry regiments not by/within type but like the British,

ŕ la suite. See below:

Cavalry regiments in January 1809:

- 1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (745 men) - Colonel Przebendowski - 1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (745 men) - Colonel Przebendowski

- 2nd Uhlan Regiment (880 men) - Colonel Tyszkiewicz - 2nd Uhlan Regiment (880 men) - Colonel Tyszkiewicz

- 3rd Uhlan Regiment (719 men) - Colonel Laczynski - 3rd Uhlan Regiment (719 men) - Colonel Laczynski

- 4th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (??? men) - Colonel Mecinski - 4th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (??? men) - Colonel Mecinski

- 5th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (596 men) - Colonel Turno - 5th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (596 men) - Colonel Turno

- 6th Uhlan Regiment (691 men) - Colonel Dziewanowski - 6th Uhlan Regiment (691 men) - Colonel Dziewanowski

In November 1809 were formed:

- 7th Uhlan Regiment (840 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Zawadzki - 7th Uhlan Regiment (840 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Zawadzki

- 8th Uhlan Regiment (954 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Rozwadowski - 8th Uhlan Regiment (954 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Rozwadowski

- 9th Uhlan Regiment (936 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Przyrzychowski - 9th Uhlan Regiment (936 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Przyrzychowski

- 10th Hussar Regiment - "Golden Hussars" (803 men) - Colonel Uminski - 10th Hussar Regiment - "Golden Hussars" (803 men) - Colonel Uminski

- 11th Uhlan Regiment (899 men in squadrons) - Colonel A. Potocki - 11th Uhlan Regiment (899 men in squadrons) - Colonel A. Potocki

- 12th Uhlan Regiment (943 men in squadrons) - Colonel Rzyszczewski - 12th Uhlan Regiment (943 men in squadrons) - Colonel Rzyszczewski

- 13th Hussar Regiment - "Silver Hussars" (1.048 men !) - Colonel Tolinski - 13th Hussar Regiment - "Silver Hussars" (1.048 men !) - Colonel Tolinski

- 14th Cuirassier Regiment (610 men in 2 squadrons) - Colonel Malachowski - 14th Cuirassier Regiment (610 men in 2 squadrons) - Colonel Malachowski

The Poles formed one regiment of cuirassiers but Napoleon felt

that they were too expensive and suggested chasseurs or uhlans.

So the King of Saxony (the head of the Duchy of Warsaw) issued decree that directed the conversion

of these cuirassiers into chasseurs. Poniatowski attempted to persuade him into converting

the cuirassiers into dragoons but the King repeated his statement. Poniatowski agreed but

added that it will take a long time due to practical obstacles. Soon however erupted war

against Russia and there was no time and money for the conversion.

- 15th Uhlan Regiment (916 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Trzecieski - 15th Uhlan Regiment (916 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Trzecieski

- 16th Uhlan Regiment (661 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Tarnowski - 16th Uhlan Regiment (661 men in 4 squadrons) - Colonel Tarnowski

In 1811 each cavalry regiment raised a depot squadron of 2 companies.

Due to financial difficulties in the Grand Duchy Napoleon in early 1812 took into French

pay the 9th Uhlan Regiment.

When Napoleon liberated Lithuania (which had been part of Poland) several new regiments

were raised:

- 17th Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Tyszkiewicz - 17th Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Tyszkiewicz

- 18th Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Wawrzecki - 18th Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Wawrzecki

- 19th Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Rajecki - 19th Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Rajecki

- 20th Uhlan Regeiment - Colonel Obuchowicz - 20th Uhlan Regeiment - Colonel Obuchowicz

- 21st Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Lubanski - 21st Uhlan Regiment - Colonel Lubanski

- Lithuanian Tartar Squadron - Mustapha Murza Achmatowicz - Lithuanian Tartar Squadron - Mustapha Murza Achmatowicz

There were several regiments in the French service:

- 1st Lancer Regiment of the Guard (Old Guard) - 1st Lancer Regiment of the Guard (Old Guard)

- 3rd Lancer Regiment of the Guard (Young Guard) - 3rd Lancer Regiment of the Guard (Young Guard)

- 1st Vistula Uhlan Regiment - 1st Vistula Uhlan Regiment

- 2nd Vistula Uhlan Regiment - 2nd Vistula Uhlan Regiment

In May 1815 Napoleon issued a decree organizing the 7e Chavauleger-Lancier Polonais.

It consisted of 350 men and only 13 horses. The lancers fought on foot in the defense

of the bridges in Sevres earning Marshal Davout's praise. After Napoleon's abdication all

the foreign regiments were disbanded. The Polish units were absorbed into the Russian army

except the lancers - they refused to serve for the Tsar, were disbanded and allowed to stay

in France.

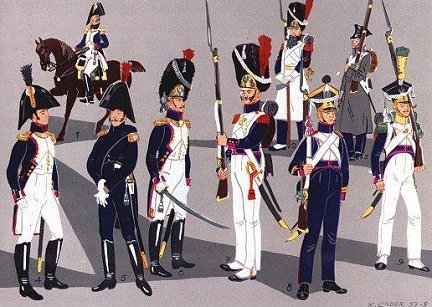

Uniforms of Polish Cavalry

The uhlans wore dark blue uniforms.

The chasseurs-a-cheval wore dark green.

The czapka was a traditional Polish headwear. The edges of the top square were

reinforced with yellow metal and white cords (red for elite companies) hung from corner

to corner. Tall black plume was worn on the front peak of the czapka

(red for elite company and white for senior officers). There were also in use some

non-regulation plumes cut "a la russe" or uncut long horse hair cascading down from the top.

(Nafziger and Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 51)

The czapka was a traditional Polish headwear. The edges of the top square were

reinforced with yellow metal and white cords (red for elite companies) hung from corner

to corner. Tall black plume was worn on the front peak of the czapka

(red for elite company and white for senior officers). There were also in use some

non-regulation plumes cut "a la russe" or uncut long horse hair cascading down from the top.

(Nafziger and Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 51)

A yellow "Amazon's Shield" bore regimental number and a white metal eagle.

Some regiments however preffered a sunburst plaque with the eagle superimposed

(the regiments formed in Lithuania wore a mounted knight instead of eagle).

Just above the turban was worn a white band (golden for officers).

All uhlans wore dark blue breeches with double side straps, dark blue coat (kurtka)

with regimental lapels and yellow buttons.

The lance pennants were of different colors:

- red over white in 2nd, 3rd, 15th and 16th Uhlan Regiment

- red over white and a dark blue triangle at the shaft of the lance

in 7th, 8th, 9th, 11th and 12th Uhlan Regiment

- blue over white in 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st Uhlan Regiment

The men of elite company of uhlan regiment wore one of the three types of headwear:

- bearskin

- colpack/busbie with red bag

- czapka sewn around with black lambskin (it lloked like bearskin)

In 1806-1809 the uhlans of 1st Division wore:

- red (piped white) collar and cuffs, yellow facings (piped white) and side straps

The uhlans of 2nd Division wore:

- crimson (piped white) collar, cuffs, facings and side straps

The uhlans in 3rd Division wore:

- white collar, cuffs, facings, and side straps

|

Uniforms of Uhlans 1809-1812

| Regiment |

Collar - Piping |

Turnbacks - Piping |

Side straps on breeches |

| 2nd |

Red - White |

Dark Blue - Yellow |

Yellow |

| 3rd |

Crimson - White |

Dark Blue - White |

Yellow |

| 6th |

White - Crimson |

Dark Blue - Crimson |

Crimson |

| 7th |

Yellow - Red |

Dark Blue - Red |

Yellow |

| 8th |

Red - Dark Blue |

Dark Blue - Red |

Red |

| 9th |

Red - Dark Blue |

Dark Blue - White |

Red |

| 11th |

Crimson - Dark Blue |

Crimson - White |

Crimson |

| 12th |

Crimson - White |

Dark Blue - White |

Crimson |

| 15th |

Crimson - White |

Crimson - White |

Crimson |

| 16th |

Crimson - White |

Dark Blue - Crimson |

Crimson |

| 17th |

Crimson - Dark Blue |

Dark Blue - Crimson |

Crimson |

| 18th |

Crimson - Dark Blue |

Crimson - White |

Crimson |

| 19th |

Yellow - Dark Blue |

Dark Blue - Yellow |

Yellow |

| 20th |

Crimson - Dark Blue |

Yellow - Dark Blue |

Yellow |

| 21st |

Orange |

Orange |

Orange or Crimson |

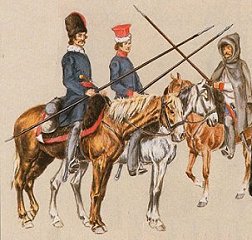

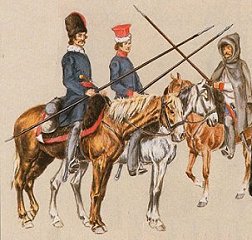

From left to right:

- trumpeter, officer, private of centre company, private of elite company of 2nd Uhlan Regiment in 1810.

- private of elite company and private of centre company of 8th Uhlan Regiment in 1810-1812.

|

The chasseurs-a-cheval wore dark green coat (kurtka) with yellow buttons and dark green

breeches. The boots were below knee. The men of elite company in every regiment wore black

busbies/colpacks with a bag in regimental color. Red plume and red cords were attached to the

headwear. The men of center companies wore shako with metal plaque and white cords.

The plume was in regimental color (tipped with dark green). The senior officers distinguished

themselves with white plumes and silver cords.

|

Uniforms of Chasseurs-a-Cheval

| Regiment |

Coat |

Collar |

Cuffs |

Turnbacks |

| 1st |

Dark Green |

Red |

Red |

Red |

| 4th |

Dark Green |

Crimson |

Crimson |

Crimson |

| 5th |

Dark Green |

Orange |

Orange |

Orange |

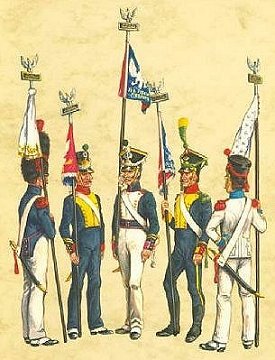

From left to right:

- trumpeter and officer of 1st Chasseur Regiment in 1812.

- private of centre company and private of elite company of 1st Chasseur Regiment in 1810-1812.

|

The hussars wore dark blue dolman and dark blue pelisse with black fur for the 10th Regiment

or white for the 13th. (Nafziger - "Poles and Saxaons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 50)

The lace between rows of buttons for officers was strung gold for the 10th Regiment and silver

for the 13th. The collar was crimson, the breches were dark blue with yellow (for 10th) or

white (for 13th) single side stripes and thigh knots. For campaign they wore grey breeches

with crimson side straps and the inside of the legs strengthened with leather. All hussars

wore Hungarian boots.

The shako was black (in 10th) or light blue (in 13th), black plumes was

attached to shakos. The men of elite company wore black busbies/colpacks with red cords and

red plumes. The senior officers distinguished themselves with gold or silver cords and white

plumes.

The cuirassiers were dressed like their French counterparts.

The breeches were white leather, the plume was red, the black boots were reaching above the

knees. The collar was red. The privates wore red epauletes, the NCOs had red with yellow

and the officers gold epauletes. The helmet and cuirass were of French model.

(Note: there were no cuirasses after 1812).

Weapons of Polish Cavalry

The primary weapons of Polish cavalry

were lance and slightly curved saber.

The uhlans were armed with saber, pistol and a lance.

The chasseurs-a-cheval were armed with sabers, carbines and were issued lances for the

1809 and 1813 campaigns (to make up for the lack of carbines).

The "Krakus" Regiment carried lances but never carbines.

The Polish cavalry could be seen to have been instrumental in the retention of the lance

until its widespread readoption in the Napoleonic period. Napoleon send Polish lancers

as instructors to the French lancer regiments. There were regulations for the exercise and

manoeuvres of the lance compiled entirely from the Polish system instituted by Prince

Poniatowski and General Krasinski. These were also adapted to the formations, movements

and exercise of the British cavalry by Reymond Hervey De Montmorency (London, 1820)

The Polish lance was 265-277 cm long. It was quite light

weapon, so much so that one could hold it between the looped forefinger and the middle finger

of the right hand raised above the head, delivering, in this manner a very powerful thrust

called "par le moulinet'. In the hands of an experienced uhlan it was an effective and

terrible weapon. (Nafziger and Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars"

p 48)

The Poles were equipped with several types of sabers:

- Polish curved sabers (produced in liberated Galicia)

- Prussian 1721 Model hussar curved saber

- Prussian 1797 Model dragoon straight "pallash"

- Austrian 1803 Model hussar curved saber

- French IX, XI and XIII Model curved and straight sabers

- Russian sabers of various models

The Poles carried captured Prussian and Austrian carbines and French 1763 and Model

1786 carbines. Many pistols were the French Model 1777.

French officer de Brack on lance.

Q: Is the lance a very effective weapon?

A: Its moral effect is the greatest, and its thrusts the most murderous of all weapons.

Q: In war, should the use of the lance conform to the directions contained in the regulations?

A: No; as a general rule the trooper must consider himself the centre of a circle whose circumference is described by the point of his weapon; but the lancer must limit his points to the half-circle in his front, and cover the rear half by the "around parry."

Q: Why?

A: The points are certain only so long as the nails are up and the forearm and body control the direction of the weapon. Where these two indispensable conditions do not exist, points which the enemy might easily parry, and which might disarm you, should not be risked. The very least objection to thrusts thus hazarded would be their uselessness, and, in war, uselessness is the synonym of ignorance and danger.

Q: What then are the "points" to which one should confine himself in action?

A: The "right-front" and "left-front" points; the "right" and "left" points against infantry; the "right," "left," and "around parries."

Q: But, should the hostile cavalry follow and press you closely?

A: Use against them the "right," "left," and "around parries," which become powerful offensive movements, when properly employed. In fact, the point cannot fail to reach the man, or the head of his horse, and the weight of the arm doubling the force of its impulsion, the enemy will be at once overthrown, or the horse be immediately stopped by the thrust.

I have witnessed a hundred illustrations of the truth of this, and, among others, may cite the case of the intrepid Captain Brou (now Colonel of the 1st Lancers), who, while near Eylau, in a charge which we made upon the Cossacks, believed himself already master of one of them, whom he had taken on his left side, and who held his lance at a "right front;" but the Cossack, standing up in his stirrups, and executing rapidly an "around parry," threw the Captain to the ground; his horse was captured, and he would have been made prisoner also, but for a courageous and skilfully executed charge made by Major Hulot, then commanding the 7th Hussars. I saw the Captain's wound dressed, and his shoulder was gashed as though cut with the edge of a sabre.

…. I have seen old Cossacks, charged by our troops with their short weapons, face and await them firmly, the point of the lance not to the front, because they judged from the boldness of the attack that their points would be parried - and that once closed in upon they would be lost - but with the lance to the right front, as in the first motion of "left parry," then responding to the attack with a "left parry," brush aside the attackers by this movement, volt to the left, and find themselves, in their turn, naturally taking the offensive by pursuing the enemy on his left.

Q: How should lance thrusts be made in action?

A: I repeat, the lance must always be held with the whole hand closed upon it, the fingers upwards, and no movement requiring the fingers to be held downwards, should be attempted, because the weight of the weapon may cause it, if parried by the enemy, to escape from the hand.

… To carry the hand to the rear only to thrust it forward again, is both useless and dangerous. Your point will always have enough spring, strength, and reach to traverse the body of a man.

… In campaign an officer should frequently inspect his lances, and see that they are kept sharp and well greased. Wounds made in the body by lances kept in good condition are almost always mortal. I have seen troopers of our army receive as many as twenty wounds, made by Cossack lances, without dying of them or even being disabled.

Q: To what do you attribute that?

A: To the inferior quality of the Cossack weapons, to the little care taken of them, and, above all, to a cause worth while to explain. The lances of the Cossacks who used to fight against us were not shod at the butt end, so, when the lancer dismounted, to avoid leaving the lance lying on the ground, he stuck the point into the soil, and thus blunted it. Hence you will remember that, under no pretext, are you to stick the point of your lance into the ground, and that it would be a hundred times better to throw it on the ground than to keep it standing up at such a cost.

The French lance needs improvement; the ash of which the staff is made is so heavy that it makes it difficult to handle, and, when carried in the socket, injures the horse's withers. The wood does not, by its strength, compensate for this disadvantage; for being cut in blocks and the grain crossed, it breaks easily and in a way that makes repairing difficult.

Another fault is the too great size of the pennons which present to the wind so large a surface that the staves are quickly bent, so that points cannot be made as accurately as they should be; quickness and lightness in handling them are diminished, and on the road the horse and the lancer's arm are uselessly fatigued by the constant backward pressure.

To correct these faults, in route marches the pennons should be removed, and attached only when it is desired to make ourselves recognized by friends or enemies; to shift the lance alternately from the right boot to the left, and frequently to remove it entirely from the boot, so that it may be carried by the lancer himself.

The rolled coat may be considered a defensive weapon. The habit of rolling it, and crossing it over the chest, in view of an engagement, has three advantages: first, it clears the opening of the pistol holster; second, it allows the bridle hand to be carried nearer to the horse's neck, which facilitates the control of the horse; and, third, it protects the trooper. But the trooper must be careful of two things: first, to so roll and cross his coat as not to be constrainted by it, and, second, in a charge to avoid being seized by it, and unhorsed and captured.

Although to lose one's arms is, generally speaking, a shame, yet there is one case where a lancer is excusable for losing his lance - that is, when he has run it clean through an enemy.

Several times, I have seen lances so well used that the weapon, caught between the ribs, after having penetrated the shoulder blade, could not possibly be withdrawn; the dying man, convulsed with pain, carried away by his horse, drew along with him the lance and the lancer vainly struggling to disengage his weapon. At Reichenbach, the bravest lancer of my regiment was killed under similar circumstances, in disobedience of my orders, through a misunderstood, stubborn sense of honor. In vain I called out to him, "Your lance is well lost"; he did not believe me, and being cut off from his comrades, was overwhelmed by numbers, and killed.

Near Lille, a young soldier of the same regiment found himself in a similar condition; I made him abandon his lance. The Prussian whom he had run through fell about 50 paces from the spot where he was wounded; we retook the ground which he had been obliged to yield for a few minutes, and my lancer having dismounted to recover his lance, succeeded in doing so only by carefully pushing it through in the same direction in which it entered.

At Waterloo, when we charged the English squares, one of our lancers, not being able to break down the rampart of bayonets which opposed us, stood up in his stirrups and hurled his lance like a spear; it passed through an infantry soldier, whose death would have opened a passage for us, if the gap had not been quickly closed. That was another lance well lost. “

Horses

Poland had large studs of horses

for light and medium cavalry.

The horses of central and eastern Europe being smaller and more agile, the first application

of their capabilities for war purposes seems everywhere to have been as light cavalry mounts.

The Poles, thanks to their wars against the Turks, Cossacks and Russians who always had

an excellent lighthorsemen, had maintained greater dash and mobility than many of the

westerners. Prussian king Frederick the Great, considered the big "German horses" as the

best suited for heavy cavalry. The "Polish horses" (Polish, Hungarian and Russian) were

considered as the best for the light cavalry and were obtained from the well-paid Jewish dealers. The king and his generals rode on

English horses. The Polish horses were used not only by Polish cavalry, but also by Saxon

hussars and chevaulegers and Prussian, Austrian and French light cavalry.

Most common colors were bays and chestnuts.

The horses of central and eastern Europe being smaller and more agile, the first application

of their capabilities for war purposes seems everywhere to have been as light cavalry mounts.

The Poles, thanks to their wars against the Turks, Cossacks and Russians who always had

an excellent lighthorsemen, had maintained greater dash and mobility than many of the

westerners. Prussian king Frederick the Great, considered the big "German horses" as the

best suited for heavy cavalry. The "Polish horses" (Polish, Hungarian and Russian) were

considered as the best for the light cavalry and were obtained from the well-paid Jewish dealers. The king and his generals rode on

English horses. The Polish horses were used not only by Polish cavalry, but also by Saxon

hussars and chevaulegers and Prussian, Austrian and French light cavalry.

Most common colors were bays and chestnuts.

The big horses for Polish 14th Cuirassier Regiment were purchased in Germany.

Poland had large studs of horses for light and medium cavalry.

Napoleon purchased thousands of Polish horses, and thousands were simply taken by the French

troops. Even in 1812. According to Vaudoncourt some of the Lithuanian uhlans survived the

campaign in Russia in pretty good shape. Unfortunatelly, the 17th and 19th Uhlan Regiment

were stripped of all their horses in an effort to remount Napoleon's cavalry of Imperial Guard.

(Nafziger - "Lutzen and Bautzen" p 9)

Chlapowski writes: "Foot drill went very well with such enthusiastic citizens as tehse, but mounted drill

was very difficult as their horses were all too lively for the ranks and kept breaking up

the lines. One should avoid putting over-lively horses in the ranks, as horses always become

livelier still when brought together."

(Chlapowski / Simmons - p 9)

In 1812 the cavalry was excellent. Chlapowski writes: "I was most impressed by the

appearanace of Prince Sulkowski's cavalry division. They had a good soldierly appearance

and their horses were magnificent. ... the 5th Chasseurs, who were very fine and even

better mounted than the 13th 'Silver' Hussars."

The Krakus Regiment

Napoleon called them “my pygmy cavalry.”

But when they began maneuvering,

deploying, charging and ploying,

all in a very fast pace, his amusement

switched to admiration.

The Krakusi Regiment, pronounced crack-coosee, was formed in 1813.

On 25th September 1813 on the road to Bautzen the Polish troops met Napoleon.

The Emperor reviewed the Krakus Regiment mounted on their peasant ponies and

laughed out loud. He called them “my pygmy cavalry.” But when they began maneuvering,

deploying, charging and ploying, all in a very fast pace, his amusement switched to admiration. In the end of the review individual riders presented their incredible skills.

Stones were placed on the ground and they came at speed picking them off the ground with

easy. They were the wizards of the saddle. Impressed Napoleon called for the commanders of French cavalry and said: look at these

kids. They are superb horsemen, they captured allied general, Cossack standard and dozens of prisoners.

And they accomplished it in short time.

The Krakusi Regiment, pronounced crack-coosee, was formed in 1813.

On 25th September 1813 on the road to Bautzen the Polish troops met Napoleon.

The Emperor reviewed the Krakus Regiment mounted on their peasant ponies and

laughed out loud. He called them “my pygmy cavalry.” But when they began maneuvering,

deploying, charging and ploying, all in a very fast pace, his amusement switched to admiration. In the end of the review individual riders presented their incredible skills.

Stones were placed on the ground and they came at speed picking them off the ground with

easy. They were the wizards of the saddle. Impressed Napoleon called for the commanders of French cavalry and said: look at these

kids. They are superb horsemen, they captured allied general, Cossack standard and dozens of prisoners.

And they accomplished it in short time.

Then he asked the generals; who of you brought me a Cossack as prisoner in the last or this

campaign ? Then he turned to General Uminski and said: I want 3.000 of such warriors.

"Generale, musze miec takich 3.000 ludzi". (Morawski & Wielecki - "Wojsko Ksiestwa

Warszawskiego", Vol I p 122)

In 1813 the officers gave commands by waving a handkerchief, in 1814 this function was

performed by using a horsetail on a pike in the manner of the wild Tartars. It was excellent tool for small warfare

as the regular cavalry used the trumpets for communication, more suited for noisy battlefield than for chasing the

elusive Cossacks.

In 1814 the privates adopted an unusual melon-like crimson beret.

The Krakus wore the folk costume of the Krakow region. The headwear was called krakuska and consisted of square topped but

soft (hard for uhlans and infantry) czapka without the visor. The krakuska

was red with black or white lambskin turban. Some privates wore captured Cossack colpacks.

The cockade and plume were white. Their single breasted and full skirted coat was either brown or white with embroidery and

appliques. The collar and cuffs were crimson with white piping. A crimson sash was worn

at the waist. The legwears were either wide pantaloons (Cossack type) or tight breeches.

In 1814 the privates adopted an unusual melon-like crimson beret.

The Krakus wore the folk costume of the Krakow region. The headwear was called krakuska and consisted of square topped but

soft (hard for uhlans and infantry) czapka without the visor. The krakuska

was red with black or white lambskin turban. Some privates wore captured Cossack colpacks.

The cockade and plume were white. Their single breasted and full skirted coat was either brown or white with embroidery and

appliques. The collar and cuffs were crimson with white piping. A crimson sash was worn

at the waist. The legwears were either wide pantaloons (Cossack type) or tight breeches.

The privates were armed with lances (with or without pennants), sabers and pistols.

No carbines, no musketoons, no rifles.

The Krakus Regiment was a valuable unit for Napoleon. Some of the privates and

officers spoke German and Russian language, their uniforms, horses and weapons were cheap

and they beat the hell out of the Cossacks as no other French or Polish unit.

Below are descriptions of several combats between the Krakus and the Cossacks.

The Krakus Regiment was a valuable unit for Napoleon. Some of the privates and

officers spoke German and Russian language, their uniforms, horses and weapons were cheap

and they beat the hell out of the Cossacks as no other French or Polish unit.

Below are descriptions of several combats between the Krakus and the Cossacks.

On 5th September 1813 the Krakus met several sotnias of Cossacks between Ebersbach, Sluknow and

Kottmarsdorf. Two squadrons of Krakus under Major Rzuchowski attacked from the front,

while one squadron under Captain Celinski moved around enemy's flank to cut it off from Herrnhut.

The Cossacks were routed and lost 98 men (30 killed, 18 wounded and 50 were taken prisoner). The Krakus also captured

approx. 100 horses. The Krakus lost 3 wounded.

(Lukasiewicz - "Armia Ksiecia Jozefa, 1813" p 239)

On 9th September 1813 at Strahwalde, General Uminski with Krakus Regiment (4 squadrons)

and the Polish 14th Cuirassier Regiment (1-2 squadrons) charged against several sotnias of

Cossacks and some dragoons (2 squadrons).

The Cossacks fled before contact was made. The Krakus pursued them for a while and then

made a turn and attacked the dragoons fleeing before the cuirassiers (no armor).

The enemy lost 35 (incl. 10 prisoners), the Poles had 6 wounded.

In this combat NCO Godlewski of the Krakussi captured standard of Grekov-V's Cossack Regiment.

The trophy was immediately sent to Napoleon and Godlewski was awarded with two awards: French Legion d'Honneur and Polish Virtuti

Militari. Unfortunately the standard was lost later on when the Russians captured an adjutant with it.

(Lukasiewicz - "Armia Ksiecia Jozefa, 1813" p 242)

The Krakus and squadron of cuirassiers were finally halted at Ebersdorf by Russian tirailleurs

(foot jagers in skirmish order ?)

In Gossnitz the regiment of Russian Soumy Hussars attacked part of the Krakus Regiment

and took 60 prisoners. Edouard von Lowenstern writes: "In Gossnitz we bumped into the Krakau Cossacks, we flew at them,

cut them up and - as they were badly mounted - captured some 60 of them."

On 16th October 1813 near Wachau (south of Leipzig) the Krakus routed the Lifeguard

Cossack Regiment. (Morawski & Wielecki - "Wojsko Ksiestwa Warszawskiego", Vol I, p 122

and Lukasiewicz - "Armia Ksiecia Jozefa, 1813" p 281)

The Best Regiments of Polish Cavalry

According to George Nafziger's "Imperial Bayonet" (publ. in 1996, page 192), author of numerous books, the best cavalry were:

According to George Nafziger's "Imperial Bayonet" (publ. in 1996, page 192), author of numerous books, the best cavalry were:

1st tier cavalry:

Saxony,

Poland,

France,

Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt

2nd tier cavalry:

Prussia,

Russia,

Britain and Northern Italy

3rd tier cavalry:

Austria,

Wirtembergia, Bavaria, Hesse-Kassel, Westphalia

4th tier cavalry:

Sweden, Spain, Portugal and Naples (Southern Italy)

The quality of the Polish cavalry regiments varied, the best were the Guard Lancers and the

Vistula Uhlans. The uhlans were the most numerous, some regiments were excellent (2nd, 3rd, 4th,

6th and 8th) while others were below the average. All three chasseurs regiments were superb.

Below is a list of the best Polish cavalry regiments.

- 3rd Uhlan Regiment (3-ci Pulk Ulanów)

31 Battles:1807 - Szczytno, Passenheim, Ortelsburg, 1809 - Czestochowa, Nadarzyn (14th,17th,19th April), Grojec, Raszyn, Grochow, Radzymin (26th,27th April), Grochow, Slupca, Wielatow, siege of Zamosc, Zawady, Zaleszczyki, Horodenka, Tarnopol, Chorostkow, Wieniawka, 1812 - Mir, Borodino, 1813 - Gross-Schweidnitz, Altenburg, Penig, Wachau, Leipzig, detachment dfending Zamosc

Colonels: Jun 1807 - Wojciech Mecinski, Tadeusz Tyszkewicz, 1812 - Augustyn Trzecieski, Alexander Radzyminski, Jan 1813 - Alexander Oborski

- 1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (1-szy Pulk Strzelców Konnych)

21 Battles: 1806 - Pultusk, 1807 - Tczew, siege of Gdansk, 1809 - Raszyn, Radzymin, Gora, Rozki, Sandomierz (on 6th,7th,15th,16th June), Wrzawy, 1812 - Grodno, Romanow, 1813 - Rumburg, Kirschenstein, Seidenberg, Haesslich, Altenburg, Penig, Wachau

Colonels: Dec 1806 - Michal Dabrowski, Nov 1808 - Konstanty Przebendowski, Jan 1813 - Jozef Sokolnicki

- 5th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (5-ty Pulk Strzelców Konnych)

19 Battles: 1807 - Tczew, Gdansk, Guttstadt, Heilsberg, Friedland, 1809 - Grzybow, Wiazownia, Gora, Kock, Sandomierz (17th,18th May), Rozki, Baranow, Nowe Miasto, Wrzawy,

1812 - Smolensk, Borodino, Chirikovo, Woronovo

Colonels: Dec 1806 - Kazimierz Turno, March 1810 Zygmunt Kurnatowski

- 13th Hussar Regiment (13-ty Pulk Huzarów)

15 Battles: 1812 - Mir, Romanow, Smolensk, Borodino, Chirikovo, Woronovo, Maloyaroslavetz, Borisov, Beresina, 1813 - Hellensdorf, Peterswalde, Sere, Pirna (9th Oct), Dresden, Pirna (17 Sept)

Colonels: June 1809 - Jozef Tolinski, Feb 1813 - Jozef Sokolnicki

- Krakus Regiment (Pulk Krakusów)

14 Battles: 1813 - Skarszew, Friedland, Georgenwalde, Strohweide, Neustadt, Frohburg, Luntzenau, Zehma, Rotha, Zetlitz, Wachau, Leipzig, 1814 - Claye, Paris

Colonels:Mar 1813 - Alexander Oborski, Jan 1814 Jozef Dwernicki

This unit existed only 2 years.

- 14th Cuirassier Regiment (14-ty Pulk Kirasjerów)

7 Battles: 1812 - Borodino, 1813 - Friedland, Pittersbach, Krakau, Strohweide, Weida, Leipzig

Colonels: Sep 1809 - Stanislaw Malachowski, Jan 1813 - Kazimierz Dziekonski

|

The Polish infantry maneuvered more swiftly than the French infantry

(according to Lejeune). In terms of marksmanship, although the Poles were better

marksmen than the French they had worse weapons. They used old Prussian muskets, captured

Russian and Austrian weapons, and even some Italian muskets.

The Polish infantry maneuvered more swiftly than the French infantry

(according to Lejeune). In terms of marksmanship, although the Poles were better

marksmen than the French they had worse weapons. They used old Prussian muskets, captured

Russian and Austrian weapons, and even some Italian muskets.

Picture: Polish infantry in firefight. By Giseppe Rava, Italy.

Picture: Polish infantry in firefight. By Giseppe Rava, Italy.  French Marshal Davout reviewed the infantry and selected three of the best regiments

(4th, 7th and 9th). These troops were sent to Spain where already was the Vistula Legion

(infantry and cavalry).

French Marshal Davout reviewed the infantry and selected three of the best regiments

(4th, 7th and 9th). These troops were sent to Spain where already was the Vistula Legion

(infantry and cavalry).

Picture: Polish infantry wore dark blue trousers made of warm wool in winter,

and white trousers made of cloth in summer.

Picture: Polish infantry wore dark blue trousers made of warm wool in winter,

and white trousers made of cloth in summer.

The grenadiers, voltigeurs and fusiliers distinguished themselves with colors of plumes and pompons. For grenadiers they were red,

for fusiliers were black and for voltigeurs light green (in 1812 yellow over green). For officers were white.

The grenadiers, voltigeurs and fusiliers distinguished themselves with colors of plumes and pompons. For grenadiers they were red,

for fusiliers were black and for voltigeurs light green (in 1812 yellow over green). For officers were white.

The Polish artillery of the Napoleonic Wars was of excellent quality, well trained although

too few in numbers and partially equipped with older guns. The artillery was very effective

in

The Polish artillery of the Napoleonic Wars was of excellent quality, well trained although

too few in numbers and partially equipped with older guns. The artillery was very effective

in  In 1807-1808 the Polish artillery was commanded by General Wincenty Axamitowski.

The first company of foot artillery was completed in Poznan (Posen) on 29th December 1806.

Another company was organized in the captured fortress of Czestochowa.

In 1807-1808 the Polish artillery was commanded by General Wincenty Axamitowski.

The first company of foot artillery was completed in Poznan (Posen) on 29th December 1806.

Another company was organized in the captured fortress of Czestochowa.

Between 1807 and 1810 the foot gunners wore dark green coats called kurtka with

black collar, lapels, cuffs, cuff flaps and turnbacks - all piped red. The buttons were

yellow. The privates wore red epauletes, cords and pompons. The trousers were black with

dark green side stripes, their gaiters were black and just under knee. The shako was black

and bore a brass plaque with a white metal eagle over crossed guns with a brass grenade.

Between 1810 and 1813 the vest and summer trousers and gaiters were white. If dark green

breeches were worn, black gaiters completed the outfit.

Between 1807 and 1810 the foot gunners wore dark green coats called kurtka with

black collar, lapels, cuffs, cuff flaps and turnbacks - all piped red. The buttons were

yellow. The privates wore red epauletes, cords and pompons. The trousers were black with

dark green side stripes, their gaiters were black and just under knee. The shako was black

and bore a brass plaque with a white metal eagle over crossed guns with a brass grenade.

Between 1810 and 1813 the vest and summer trousers and gaiters were white. If dark green

breeches were worn, black gaiters completed the outfit.

Picture: Polish uhlans, reenactors. Photo from

Picture: Polish uhlans, reenactors. Photo from

The Polish cavalry regiment consisted of staff and usually 3 (in 1806-1809) or 4 squadrons of two

companies each. The 4-squadron regiment was commanded by colonel, major, 2 chefs d'escadron

and 2 adjutanbts-majors. There were also standard-bearer and trumpet-major.

The Polish cavalry regiment consisted of staff and usually 3 (in 1806-1809) or 4 squadrons of two

companies each. The 4-squadron regiment was commanded by colonel, major, 2 chefs d'escadron

and 2 adjutanbts-majors. There were also standard-bearer and trumpet-major.

The czapka was a traditional Polish headwear. The edges of the top square were

reinforced with yellow metal and white cords (red for elite companies) hung from corner

to corner. Tall black plume was worn on the front peak of the czapka

(red for elite company and white for senior officers). There were also in use some

non-regulation plumes cut "a la russe" or uncut long horse hair cascading down from the top.

(Nafziger and Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 51)

The czapka was a traditional Polish headwear. The edges of the top square were

reinforced with yellow metal and white cords (red for elite companies) hung from corner

to corner. Tall black plume was worn on the front peak of the czapka

(red for elite company and white for senior officers). There were also in use some

non-regulation plumes cut "a la russe" or uncut long horse hair cascading down from the top.

(Nafziger and Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 51)

The horses of central and eastern Europe being smaller and more agile, the first application

of their capabilities for war purposes seems everywhere to have been as light cavalry mounts.

The Poles, thanks to their wars against the Turks, Cossacks and Russians who always had

an excellent lighthorsemen, had maintained greater dash and mobility than many of the

westerners. Prussian king Frederick the Great, considered the big "German horses" as the

best suited for heavy cavalry. The "Polish horses" (Polish, Hungarian and Russian) were

considered as the best for the light cavalry and were obtained from the well-paid Jewish dealers. The king and his generals rode on

English horses. The Polish horses were used not only by Polish cavalry, but also by Saxon

hussars and chevaulegers and Prussian, Austrian and French light cavalry.

Most common colors were bays and chestnuts.

The horses of central and eastern Europe being smaller and more agile, the first application

of their capabilities for war purposes seems everywhere to have been as light cavalry mounts.

The Poles, thanks to their wars against the Turks, Cossacks and Russians who always had

an excellent lighthorsemen, had maintained greater dash and mobility than many of the

westerners. Prussian king Frederick the Great, considered the big "German horses" as the

best suited for heavy cavalry. The "Polish horses" (Polish, Hungarian and Russian) were

considered as the best for the light cavalry and were obtained from the well-paid Jewish dealers. The king and his generals rode on

English horses. The Polish horses were used not only by Polish cavalry, but also by Saxon

hussars and chevaulegers and Prussian, Austrian and French light cavalry.

Most common colors were bays and chestnuts.

The Krakusi Regiment, pronounced crack-coosee, was formed in 1813.

On 25th September 1813 on the road to Bautzen the Polish troops met Napoleon.

The Emperor reviewed the Krakus Regiment mounted on their peasant ponies and

laughed out loud. He called them “my pygmy cavalry.” But when they began maneuvering,

deploying, charging and ploying, all in a very fast pace, his amusement switched to admiration. In the end of the review individual riders presented their incredible skills.

Stones were placed on the ground and they came at speed picking them off the ground with

easy. They were the wizards of the saddle. Impressed Napoleon called for the commanders of French cavalry and said: look at these

kids. They are superb horsemen, they captured allied general, Cossack standard and dozens of prisoners.

And they accomplished it in short time.

The Krakusi Regiment, pronounced crack-coosee, was formed in 1813.

On 25th September 1813 on the road to Bautzen the Polish troops met Napoleon.

The Emperor reviewed the Krakus Regiment mounted on their peasant ponies and

laughed out loud. He called them “my pygmy cavalry.” But when they began maneuvering,

deploying, charging and ploying, all in a very fast pace, his amusement switched to admiration. In the end of the review individual riders presented their incredible skills.

Stones were placed on the ground and they came at speed picking them off the ground with

easy. They were the wizards of the saddle. Impressed Napoleon called for the commanders of French cavalry and said: look at these

kids. They are superb horsemen, they captured allied general, Cossack standard and dozens of prisoners.

And they accomplished it in short time.

In 1814 the privates adopted an unusual melon-like crimson beret.

The Krakus wore the folk costume of the Krakow region. The headwear was called krakuska and consisted of square topped but

soft (hard for uhlans and infantry) czapka without the visor. The krakuska

was red with black or white lambskin turban. Some privates wore captured Cossack colpacks.

The cockade and plume were white. Their single breasted and full skirted coat was either brown or white with embroidery and

appliques. The collar and cuffs were crimson with white piping. A crimson sash was worn

at the waist. The legwears were either wide pantaloons (Cossack type) or tight breeches.

In 1814 the privates adopted an unusual melon-like crimson beret.

The Krakus wore the folk costume of the Krakow region. The headwear was called krakuska and consisted of square topped but

soft (hard for uhlans and infantry) czapka without the visor. The krakuska

was red with black or white lambskin turban. Some privates wore captured Cossack colpacks.

The cockade and plume were white. Their single breasted and full skirted coat was either brown or white with embroidery and

appliques. The collar and cuffs were crimson with white piping. A crimson sash was worn

at the waist. The legwears were either wide pantaloons (Cossack type) or tight breeches.

The Krakus Regiment was a valuable unit for Napoleon. Some of the privates and

officers spoke German and Russian language, their uniforms, horses and weapons were cheap

and they beat the hell out of the Cossacks as no other French or Polish unit.

Below are descriptions of several combats between the Krakus and the Cossacks.

The Krakus Regiment was a valuable unit for Napoleon. Some of the privates and

officers spoke German and Russian language, their uniforms, horses and weapons were cheap

and they beat the hell out of the Cossacks as no other French or Polish unit.

Below are descriptions of several combats between the Krakus and the Cossacks. According to George Nafziger's "Imperial Bayonet" (publ. in 1996, page 192), author of numerous books, the best cavalry were:

According to George Nafziger's "Imperial Bayonet" (publ. in 1996, page 192), author of numerous books, the best cavalry were: