.

"If the campaigns are studied,

the French certainly owes most of

their victories to her light infantry"

- Prussian general Schanhorst

|

The Best Infantry Regiments.

Rheir Colonels, War Record and Battle Honors (1795-1815).

The French army contained many regiments of line and light infantry whose

soldierly skills and deeds of daring reflected the unsurpassed devotion of the soldiers

to their cause and to Napoleon.

They all won immortal fame in those ten

terrible years of strife.

The French army contained many regiments of line and light infantry whose

soldierly skills and deeds of daring reflected the unsurpassed devotion of the soldiers

to their cause and to Napoleon.

They all won immortal fame in those ten

terrible years of strife.

1790-1815

(line regiments)

4th Regiment d'Infanterie de Ligne

4 Battle Honors:

1796 - Arcole, 1800 - Hohenlinden,

1806 - Jena, 1809 - Wagram

37 Battles and Combats:

1791 - Expedition to Saint-Dominique,

1795 - Mannheim,

1796 - Mantoue, Castiglione, Verone, Primolano, La Brenta, Caldiero, Arcole, Tagliemento,

1798 - Expedition to the Iles Saint-Marcouf,

1800 - Engen, Moeskirch, Memmingen, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Ulm, Austerlitz,

1806 - Jena,

1807 - Eylau, Heilsberg, Koenigsberg,

1809 - Eckmuhl, Aspern, Essling, Wagram,

1812 - Smolensk, Valoutina, La Moskowa, Krasnoe,

1813 - Dresden, Leipzig, Hanau,

1814 - Brienne, La Rothiere, Monterau, Troyes,

1815 - Ligny

Notes:

In 1804 their colonel was

Joseph Bonaparte, brother of the Emperor.

In 1805 at Austerlitz the

Russian Guard cavalry captured their flag.

In 1807 at

Heilsberg the 4th was part of St.Cyr's Infantry Division.

In 1809 at

Wagram the 4th Ligne was part of Massena's Corps and - again - lost Eagle, this time

to the Austrians. In 1812 at Borodino the 4th was part of Ney's III Corps.

In 1813 at Leipzig the 4th Line regiment was part of Dufour's 5th Infantry Division and was

involved in

heavy fighting for Wachau. In 1815 at

Ligny the 4th was part of Girard's 7th Infantry Division and

attack Prussian flank.

18th Regiment d'Infanterie de Ligne "The Brave"

3 Battle honors:

1796 - Rivoli, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1812 - Borodino (La Moskowa)

38 Battles and Combats:

1792 - Jemmapes,

1796 - Dego, Lonato, Castiglione, Saint-Georges, Caldiero, Arcole, Tarvis,

1797 - Rivoli,

1798 - Fribourg, Alexandrie, Chebreiss, Pyramides,

1799 - Saint-Jean de Acre, Mont-Tabor, Aboukir,

1805 - Hollabrun, Austerlitz,

1806 - Jena,

1807 - Eylau, Heilsberg, Friedland,

1809 - Ebersberg, Vienne, Essling, Wagram, Znaim,

1812 - Smolensk, La Moskowa, Krasnoe,

1813 - Dresden, Leipzig, Hanau,

1814 - Magdebourg, La Rothiere, Montereau,

1815 - Surbourg, Strasbourg

Notes:

in 1807 at

Heilsberg the 18th was sent to outflank the Russian position.

It found itself isolated and attacked by numerous Cossacks. Two more battalions and one

battery were sent to support the 18th before it was able to withdraw.

Near Eylau, the 18th Ligne lost its flag and Eagle to the Russian

S.Petersbourg Dragoons.

In 1809 at Wagram the 18th Ligne and 26th Legere were part of Legrand's Division

(Massena's Corps). The 18th had fought at Aspern-Essling, and at Wagram and lost 45 of 54 officers killed and wounded !

At Raab the 18th delivered am audacious charge that sent the Austrians reeling and took 5 cannons.

In 1812 at Borodino this regiment was part of Ney's III Corps.

It was on 18th November 1812 at Krasne, that the 18th lost its eagle. Marshal Ney led his troops in a frontal attack that ended in

failure. According to Col. Pierre Pelleport, the 18th Regiment was

“virtually destroyed” by Russian Lifeguard Uhlans. By Pelleport's order, the

eagle was placed at the head of the regiment although other troops sought to hide

their own eagles by dismantling them or hurrying them to the rear.

Approx. 600 of the Frenchmen became casualties, including 350 dead and few

survived by the skin of their teeth. The infantry fled pell-mell across the

white field, carrying with them the few officers who were trying vainly to rally

them. Officers Koracharov and Bolchwing and uhlan Darchenko of the II Squadron

captured the eagle and flag (drapeau) of the 18th Line and were awarded with the

St. George order. The 18th Line had requested a replacement eagle for the one lost at Krasne

and Napoleon approved the request in 1813.

In 1813 at Leipzig this regiment was part of Vial's 6th Infantry Division and was

involved in

heavy fighting for Wachau.

57th Regiment d'Infanterie de Ligne "le Terible"

3 Battle Honors:

1797 - La Favorite, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1812 - Borodino (La Moskowa)

43 Battles and Combats:

1792 - Spire,

1793 - Mayence ,

1794 - Fontarabie, Pampelune,

1797 - La Favorite,

1799 - Zurich, Diessenhofen,

1800 - Engen, Moeskirch, Biberach, Hochstedt, Nordlingen, Oberhausen, Neubourg, Landshut, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Memmingen, Ulm, Austerlitz,

1806 - Jena, Lubeck,

1807 - Bergfried, Deppen, Hoff, Eylau, Lomitten, Heilsberg,

1809 - Thann, Abensberg, Eckmuhl, Ratisbonne, Essling, Wagram,

1812 - Mohilov, La Moskowa, Malojaroslavetz, Viasma, Krasnoe,

1813 - Dresden, Pirna, Kulm, Rachnitz,

1814 - Strasbourg

Notes:

In 1805 at Austerlitz the 10th was part of Vandamme's Infantry Division and

participated in the

storming of Pratzen Heights. It was one of the most decisive moments of this epic battle.

In 1807 at

Heilsberg the 57th was part of St.Cyr's Infantry Division. They stormed the redoubts in the center

of Russian positions. The Russians counterattacked and the fighting was tremendous.

In 1809 at Wagram the 57th Ligne and 10th Legere were part of Grandjean's Infantry Division (Oudinot's Corps)

In 1812 at Borodino this reegiment was part of Davout's I Corps and they

captured one of the Bagration Fleches. It was one of the bloodiest fights of the Napoleonic Era.

Napoleon said: "The Terrible 57th which nothing can stop." These words were proudly

added to their flag. The Directory ordered such inscriptions removed, thereby proving once more that they knew nothing

about solders.

84th Regiment d'Infanterie de Ligne "One Against Ten"

2 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm 1805, 1812 - Wagram

30 Battles and Combats:

1792 - Valmy,

1794 - Oneille,

1795 - Saint-Martin-de-Lantosca,

1796 - Borghetto, Mantua, Cerea, Bassano,

1800 - Engen, Moeskirch, Hochstedt,

1805 - Ulm, Austerlitz,

1809 - Sacile, Prewald, Graetz, Wagram,

1812 - Ostrowo, Smolensk, La Moskowa, Malojaroslawetz, Krasnoe, La Beresina,

1813 - Feistritz, Laybach, Isonzo, Caldiero,

1814 - Verone, Mincio, Plaisance,

1815 - Waterloo

Notes:

The 84th Ligne, in tribute to the victory over 10,000 Austrians at Graz in 1809,

had a silver plaque attached to the staff of its eagle with the inscription "Un Contra Dix" ("One Against Ten").

In 1809 at Wagram this regiment was part of the famous MacDonald's column.

When its eagle and flag were destroyed in 1812 in Russia, its colonel saved the plaque.

85th Regiment d'Infanterie de Ligne

6 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1807 - Eylau, 1807 - Friedland,

1809- Essling, Wagram

38 Battles and Combats:

1795 - Loano,

1796 - Mondovi, Borghetto, Lonato, Castiglione, Roveredo, Rivoli,

1797 - Tramin, Gorges

1798 - Malte, Chebreiss, Les Pyramides,

1799 - El-Arish, Saint-Jean-d'Acre

1800 - Heliopolis

1805 - Ulm, Austerlitz,

1806 - Auerstadt, Custrin, Czarnovo, Pultusk,

1807 - Eylau, Friedland ,

1809 - Eckmuhl, Ratisbonne, Wagram,

1812 - Mohilew, La Moskowa, Wiasma, Smolensk, Krasnoe, Wilna,

1813 - Pirna, Kulm, Dresden,

1814 - Laon, Paris.

1815 - Waterloo

Notes:

In 1809 at Wagram the 85th Ligne was part of Gudin's Infantry Division (Davout's Corps)

1790-1815

(light regiments)

1st Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

3 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm, , 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Friedland

47 Battles and Combats:

1792 - Spiere, Mayennce,

1793 - Le Boulou, Collioure, Saint-Laurent-de-la-Muga,

1794 - Le Montagne-Noire, Rosas,

1795 - Loano, Bardinetto,

1797 - Armee du Nord,

1799 - Zurich, Stokach,

1800 - Moeskirch, Bregenz, Mont Tonale, Hohenlinden,

1806 - Lago-Negro, Monterano, Sainte-Euphemie, Sigliano,

1807 - Strongoli,

1808 - Valence and Tarragone,

1809 - Vals, Saint-Hilary, Raab, Presbourg, and Saint-Colomba,

1810 - Grenouillere, Montblanc, and Salona,

1811 - Tarragone, Saint-Celoni, and Serrat,

1813 - Bautzen, Lukau, Juterbock, Dessau, Leipzig, and Zara,

1814 - Chalons-sur-Marne, Mincio, Bar-sur-Aube, Saint-Georges, Saint-Romans,

1815 - Ligny, Waterloo

Notes:

In 1813 at Dennewitz the 1st

was part of Pacthod's 13th Division (Oudinot's XII Corps).

In 1815 at Quatre Bras

they had thrown back Wellington's charges. At Waterloo this regiment was heavily involved in the attacks on Hougoumont chateau.

6th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

7 Battle Honors:

1800 - Marengo, 1805 - Ulm, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, Friedland , 1809 - Essling,

Wagram

41 Battles and Combats:

1795 - Pirmassens

1796 - Mantua, Castiglione.

1800 - Romano, Montebello, Marengo, Gazzoldo, Goito, Pozzolo,

1805 - Elchingen, Ulm, Austerlitz,

1806 - Jena, Lubeck,

1807 - Eylau, Peterswald, Guttstadt, Friedland,

1809 - Villafranca, San-Payo, Santiago,

1809 - Essling, Wagram,

1810 - Cuidad-Rodrigo, Almeida, Busaco,

1811 - Fuentes-de-Onoro,

1812 - Arapiles,

1813 - Lutzen, Bautzen, Buntzlau, Potznitz, Leipzig,

1814 - La Rothiere, Vauchamps, Montmirail, Craonne, Orthez, Toulouse,

1815 - Ligny, Waterloo

Notes:

In 1791 their colonel was Thomas O'Meara [Irishman],

in 1815 at Ligny the 6th was part of Pecheux's 12th Infantry Division and

attacked the village of Ligny in the very center of Prussian possitions.

9th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère "Incomparable"

4 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm, 1807 - Friedland, 1809 - Essling and Wagram.

35 Battles and Combats:

1793 - Neerwinden , Arlon,

1794 - Fleurus, Mayence,

1795 - Ehrenbreitstein,

1800 - Romano, Marengo,

1805 - Ulm, Durrenstein, Vienne, Halle, Lubeck, 1806 - Waren, 1807 - Mohrengen, Eylau,

Braunsberg, Friedland, 1808 - Madrid, 1809 - Medellin and Talevera,

1809 - Essling and Wagram, 1811 - Chiclana and Fuentes-de-Onoro, 1812 - Badajoz and Bornos,

1813 - Vittoria, 1813 - Lutzen, Bautzen, Kulm, Peterswald, and Leipzig, 1814 - Toulouse,

Santa-Maria de la Nieva, 1814 - Montmirail, 1815 - Ligny

Notes:

There were quarels between the Consular Guard and the 9th Light , which - Napoleon having dubbed it "The Incomparable"

in Italy - was not about to be impressed by any "Praetorians." In 1808 the 9th participated in the

storming of the Somosierra Pass in Spain.

10th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

7 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm and Austerlitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, 1809 - Eckmuhl, Essling and Wagram.

38 Battles and Combats:

1795 - Dusseldorf,

1796 - Rastadt, Neresheim, Kehl, Biberach,

1799 - Limmath, Zurich,

1800 - Engen, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Ulm and Austerlitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, Heilsberg,

Friedland, 1809 - Thann, Landshut, Eckmuhl, Essling, and Wagram, 1812 - Alba, Carascal,

Estella, 1812 - Smoliany, Borisow, 1813 - Pampelune and Roncal, Lutzen, Kulm, Buntzlau,

Naumbourg, Dresden, Leipzig, Hanau, 1814 - Vauchamps, Bar-sur-Aube, and Arcis-sur-Aube,

1815 - Strasbourg

Notes:

In 1805 at Austerlitz the 10th was part of St.Hilaire Infantry Division and

participated in the

storming of Pratzen Heights. It was one of the most decisive moments of this epic battle.

In 1807 at

Heilsberg this regiment was part of St.Hilaire's Infantry Division and attacked the

Russian center. In 1809 at Wagram the 10th Legere and 57th Ligne "The Terible" were

part of Grandjean's Infantry Division (Oudinot's Corps)

11e Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

- Battle Honors:

none

39 Battles and Combats:

1794 - Schanzel, Kaiserlautern, Mayence, Mombach,

1795 - Loano,

1796 - La Bochetta-di-Campione, La Corona, Lonato, Saint-Georges, Tyrol, Lavis, Brixen,

1797 - Rivoli, Mantua, Valvasonne,

1798 - Malta,

1799 - Offenbourg, Stockach, Trebbia,

1800 - Fischbach,

1802 - Gros-Morne, Crete-a-Pierrot, La Cap, Vertieres,

1812 - Sivotschina, Soolna, Polotsk, Beresina,

1813 - Dresden, Leipzig, Hanau,

1814 - Brienne, La Rothiere, Valjouan, Monterau, Troyes,

Notes:

In 1803 this unit was disbanded and the number 11e was remaining vacant until 1811.

In 1811 the regiment was formed of several famous battalions:

Bataillon de Tirailleurs Corses, Bataillon de Tirailleurs du Po, Bataillon de Tirailleurs de la Legion de Midi,

and Bataillon Valaison. In 1813 at Leipzig this regiment was part of Vial's 6th Infantry Division and was

involved in heavy fighting for Wachau. In 1815 at

Ligny the 11e was part of Girard's 7th Infantry Division and

attack Prussian flank

13th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

5 Battle Honors:

1805 - Austerlitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, 1809 - Eckmuhl, Wagram

25 Battles and Combats:

1792 - Valmy,

1793 - Wattignies,

1795 - Dusseldorf,

1796 - Ireland,

1800 - Melagnano, Volta, Mincio, Passage of the Adige,

1805 - Austerlitz,

1806 - Auerstadt,

1807 - Landsberg, Eylau,

1809 - Rohr, Landshut, Ratisbonne, Dunaberg, Wagram,

1812 - Smolensk, Moskova, Viasma, Krasnoe, Beresina,

1813 - Dresden, Kulm,

1815 - Waterloo

Notes:

In 1809 at Wagram the 13th Legere was part of Morand's Infantry Division (Davout's Corps).

In 1812 at Borodino this regiment was part of Morand's 1st Infantry Division (Davout's Corps)

and participated in the

attacks on Great Redoubts (also called Raievski Redoubt and Death Redoubt).

In 1815 at Waterloo the 13th Légère

captured farm of La Haye Sainte, in the very center of Wellington's positions.

24th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

6 Battle Honors:

1805 - Austerlitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, 1809 - Eckmuhl, Essling, Wagram

26 Battles and Combats:

1797 - Mayence,

1800 - Montebello, Marengo,

1805 - Austerlitz, 1807 - Bergfied, Eylau, Lomitten, Heilsberg,

Friedland, 1808 - Andujar, 1809 - Essling, Wagram, Znaim, 1812 - Krasnoe, Smolensk, Valoutina,

Borodino, 1813 - Bautzen, Dresden, Leipzig, 1814 - Commercy, Brienne, La Rothiere,

Monterau, Bar-sur-Aube, Arcis-sur-Aube

Notes:

In 1807 at

Heilsberg the 24th was part of St.Cyr's Infantry Division.

In 1809 at Aspern-Essling the 24th Light's in brilliant bayonet charge overran Austrian battery.

The French took 700 prisoners and recaptured the church.

Unfortunatelly at Wagram

the 24th lost their Eagle to the Austrians.

In 1812 at Borodino this regiment was part of Ney's III Corps.

In 1814 at La Rothiere

one battalion of this regiment was involved in the stubborn defense of La Rothiere against repeated attacks of

the Russian infantry.

25th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

6 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau and Friedland, 1809 - Essling and Wagram

30 Battles and Combats:

1796 - Altenkirchen

1799 - Stokach, Le Grimsel,

1800 - Hermette, Mincio, Valeggio,

1805 - Gunzberg, Scharnitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Allenstein, Guttstadt, Friedland,

1808 - Saragosse and Cascantes, 1809 - Tamammes, 1809 - Essling, Wagram,

1810 - Cuidad Rodrigo, Alcoba, 1811 - Redhina, Foz-do-Aronce, Miranda-del-Corvo,

1812 - Salamanca (Arapiles), 1813 - Lerin and Muz, 1813 - Lutzen, Wurschen, Buntzlau, Leipzig,

1814 - Toulouse

Notes:

In 1812 at Salamanca the 25th Legere Light and 27th Ligne attacked while the British

line hesitated and stood firm for a moment. The British

Redcoats then broke and fled.

26th Regiment d'Infanterie Légère

7 Battle Honors:

1805 - Ulm and Austerlitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, 1809 - Eckmuhl, Essling and Wagram

30 Battles and Combats:

1800 - Suze, Brunette, Bosano,

1805 - Ulm and Austerlitz, 1807 - Hoff, Eylau, Heilsberg, and Konigsberg

1808 - Saragosse, Andujar, Baylen,

1809 - Eckmuhl, Ebersberg, Essling, Wagram, Hollabrun, Znaim, 1812 - Oboiardszino, Polotsk,

Torezacew, Borisow, Beresina, 1813 - Hambourg, Dresden, Leipzig, Freibourg, Hanau,

1814 - Ligny, Brienne

Notes:

In 1807 at Heilsberg the 26th was heavily involved in the

ferocious fighting for the redoubts.

In 1808 at

Baylen they surrendered to the Spaniards.

In 1809 at Wagram the 26th Legere was part of Legrand's Infantry Division (Massena's Corps).

In 1813 at Leipzig this regiment was part of Dufour's 5th Infantry Division and was

involved in

heavy fighting for Wachau. One battalion of the 26th (made of raw recruits) was crushed

by the Prussian landwehr and reserve infantry at Hagelberg.

Battle Honors

1795-1815 |

light regiments |

line regiments |

| 7 |

6th Légère

10th Légère

26th Légère |

-

-

- |

| 6 |

24th Légère

25th Légère |

85th Ligne

- |

| 5 |

13th Légère

16th Légère

27th Légère |

94th (95th ?) Ligne

-

- |

| 4 |

7th Légère

9th Légère "Incomparable"

17th Légère

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- |

4th Ligne, 13th Ligne,

24th Ligne, 25th Ligne,

36th Ligne, 88th Ligne,

96th Ligne, 105th Ligne,

111th Ligne, 112th Ligne,

113th Ligne, 114th Ligne,

115th Ligne, 116th Ligne,

120th Ligne, 124th Ligne,

127th Ligne, 128th Ligne,

133rd Ligne, 136th Ligne,

142nd Ligne, 144th Ligne |

Battles and Combats

1795-1815 |

light regiments |

line regiments |

| 76 |

- |

93rd Ligne |

| 52 |

- |

28th Ligne |

| 51 |

-

- |

40th Ligne

51st Ligne |

| 49 |

-

- |

16th Ligne

24th Ligne |

| 48 |

- |

43rd Ligne |

| 47 |

1st Légère |

5th Ligne |

| 45 |

- |

39th Ligne |

| 44 |

-

- |

26th Ligne

96th Ligne |

| 43 |

-

-

-

- |

12th Ligne

34th Ligne

36th Ligne

57th Ligne "le Terible" |

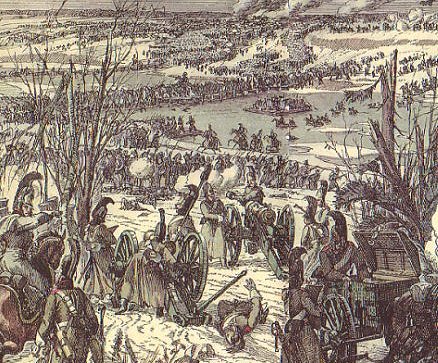

French infantry crossing the icy Berezina River in winter 1812.

Russian horse gunners (in helmets) open fire on the French.

Picture by Oleg Parkhaiev.

|

Years of almost incessant campaigning included bayonet charges, amphibious assaults, partisan

warfare, urban combat and more. But despite the glamor of the divisions of Imperial Guard and heavy cavalry, an often overlooked fact is that the mainstay of the

French army throughout the napoleonic wars was the long-suffering, hard-marching infantry regiments and battalions.

There were hardly more than dozen regiments of armored cavalry; there were rarely far fewer than two hundred infantry

regiments holding the various fronts around Europe. Unfortunately, these critical units often go almost completely unnoticed in histpories of the war.

Years of almost incessant campaigning included bayonet charges, amphibious assaults, partisan

warfare, urban combat and more. But despite the glamor of the divisions of Imperial Guard and heavy cavalry, an often overlooked fact is that the mainstay of the

French army throughout the napoleonic wars was the long-suffering, hard-marching infantry regiments and battalions.

There were hardly more than dozen regiments of armored cavalry; there were rarely far fewer than two hundred infantry

regiments holding the various fronts around Europe. Unfortunately, these critical units often go almost completely unnoticed in histpories of the war.

In 1792, every able-bodied Frenchman was declared liable for military service, and National Guard was formed.

Revolutionary France had been the first to adopt the principle of universal conscription,

according to which all young men of draft age were subject to being called up; in fact,

however, a system of drawing names was in place, and as a result, only the minority of

those eligible were enrolled every year.

Even though entering the draft lottery was

theoretically required of all male citizens, malfunction exemptions, favors and bribes -

together with every man's perfectly legal right to buy a replacement if he could afford one -

guaranteed that the burden of conscription fell principally upon the country and town folks.

Nevertheless, the army considered itself as representative of the entire society.

In 1792, every able-bodied Frenchman was declared liable for military service, and National Guard was formed.

Revolutionary France had been the first to adopt the principle of universal conscription,

according to which all young men of draft age were subject to being called up; in fact,

however, a system of drawing names was in place, and as a result, only the minority of

those eligible were enrolled every year.

Even though entering the draft lottery was

theoretically required of all male citizens, malfunction exemptions, favors and bribes -

together with every man's perfectly legal right to buy a replacement if he could afford one -

guaranteed that the burden of conscription fell principally upon the country and town folks.

Nevertheless, the army considered itself as representative of the entire society.

The new French armies, composed of demoralized regulars and untrained

volunteers, refused to face the disciplined Austrian troops and were more dangerous to

their own officers than to the enemy. The victory at Valmy stimulated the French morale,

then the Jacobin fanatics infused the

French soldiers with something of their own demonic energy.

Untrained but enthusistic volunteers filled the ranks.

In the spirit of liberty and equality, the volunteers elected their officers, and discipline

all but disappeared.

The new French armies, composed of demoralized regulars and untrained

volunteers, refused to face the disciplined Austrian troops and were more dangerous to

their own officers than to the enemy. The victory at Valmy stimulated the French morale,

then the Jacobin fanatics infused the

French soldiers with something of their own demonic energy.

Untrained but enthusistic volunteers filled the ranks.

In the spirit of liberty and equality, the volunteers elected their officers, and discipline

all but disappeared.

During 1793-1796, the infantry was reorganized into demi-brigades, each with 1

battalion of old soldiers and 2 battalions of volunteers, in the hope of combining

regular steadiness with volunteer enthusiasm. Initially, the result was that each

element qcquired the other's bad habits. There was no time to drill the disorerly

recruits into the robot steadiness and precision demanded by linear system.

(Esposito, Elting - "A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars")

During 1793-1796, the infantry was reorganized into demi-brigades, each with 1

battalion of old soldiers and 2 battalions of volunteers, in the hope of combining

regular steadiness with volunteer enthusiasm. Initially, the result was that each

element qcquired the other's bad habits. There was no time to drill the disorerly

recruits into the robot steadiness and precision demanded by linear system.

(Esposito, Elting - "A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars")

Every infantryman was armed with musket, bayonet, and carried a knapsack,

water bottle, and blanket or greatcoat, besides an ammunition pouch.

According to David Chandler "Training remained rudimentary. The new conscript might receive 2 or 3 weeks of

basic instruction at the depot, but he would fire on average only two musket shots a year in practice. Much stress was placed upon

the attack with cold steel ..." (Chandler - "Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars" pp 207-208)

Every infantryman was armed with musket, bayonet, and carried a knapsack,

water bottle, and blanket or greatcoat, besides an ammunition pouch.

According to David Chandler "Training remained rudimentary. The new conscript might receive 2 or 3 weeks of

basic instruction at the depot, but he would fire on average only two musket shots a year in practice. Much stress was placed upon

the attack with cold steel ..." (Chandler - "Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars" pp 207-208)

Many of the victories from 1805 to 1807 were both easy and decisive.

In 1806 and 1807 "In action, the infantry was still splendid, and did not as yet require to be formed in deep columns of many battalions,

such as was Macdonald's at Wagram, three years later."

(Petre - "Napoleon's Campaign in Poland, 1806-1807" pp 27-28)

Many of the victories from 1805 to 1807 were both easy and decisive.

In 1806 and 1807 "In action, the infantry was still splendid, and did not as yet require to be formed in deep columns of many battalions,

such as was Macdonald's at Wagram, three years later."

(Petre - "Napoleon's Campaign in Poland, 1806-1807" pp 27-28)

The Battle of Austerlitz was a glory day for the French infantry.

Napoleon had strong centre under Generals Vandamme and St.

Hilaire climb the Pratzen Heights, the key position on the battlefield.

Kutuzov and part of Russian staff rode forward with Jurczik's Austrian brigade.

As they drew closer against the French center and began to deploy, the French placed

6 heavy guns behind the 36th Line Regiment (3 pieces on either end of the regiment)

and waited. Both sides deployed in almost a mirror image of each other.

The Battle of Austerlitz was a glory day for the French infantry.

Napoleon had strong centre under Generals Vandamme and St.

Hilaire climb the Pratzen Heights, the key position on the battlefield.

Kutuzov and part of Russian staff rode forward with Jurczik's Austrian brigade.

As they drew closer against the French center and began to deploy, the French placed

6 heavy guns behind the 36th Line Regiment (3 pieces on either end of the regiment)

and waited. Both sides deployed in almost a mirror image of each other.

Even in Spain many units performed gallantly.

John Burgoyne wrote in "Life and correspondence of Burgoyne": "The French regiment

came up the hill with a brisk and regular step, and their drums beating pas de charge:

our men fired wildly and at random among them; the French never returned a shot, but

continued their steady advance. The English fired again but still without return ...

and when the French were close upon them, they wavered and gave way."

Even in Spain many units performed gallantly.

John Burgoyne wrote in "Life and correspondence of Burgoyne": "The French regiment

came up the hill with a brisk and regular step, and their drums beating pas de charge:

our men fired wildly and at random among them; the French never returned a shot, but

continued their steady advance. The English fired again but still without return ...

and when the French were close upon them, they wavered and gave way."

Colonel Waller, (British 2nd Division) witnessed a French attack against Picton's "Fighting

Division" in 1810 at Bussaco: "At this moment were seen the heads of the several columns,

three I think, in number and deploying into line with the most beautiful precision, celerity

and gallantry. As they formed on the plateau, they were cannonaded from our position and

the regiment of Portuguese... threw in some volleys of musketry into the enemy's columns

in a flank direction, but the (Portugese) regiment was quickly driven into the position ...

the (French) columns advanced in despite of a tremendous fire of grape and musketry from our

troops in position in the rocks, and overcoming all opposition although repeatedly charged

by Lightburne's Brigade, or rather the whole of Picton's Div., they advanced and fairly drove

the British right wing from the rocky part of this position."

Colonel Waller, (British 2nd Division) witnessed a French attack against Picton's "Fighting

Division" in 1810 at Bussaco: "At this moment were seen the heads of the several columns,

three I think, in number and deploying into line with the most beautiful precision, celerity

and gallantry. As they formed on the plateau, they were cannonaded from our position and

the regiment of Portuguese... threw in some volleys of musketry into the enemy's columns

in a flank direction, but the (Portugese) regiment was quickly driven into the position ...

the (French) columns advanced in despite of a tremendous fire of grape and musketry from our

troops in position in the rocks, and overcoming all opposition although repeatedly charged

by Lightburne's Brigade, or rather the whole of Picton's Div., they advanced and fairly drove

the British right wing from the rocky part of this position."

Picture: "the French arrived [at Tordesillas], 60

... headed by Cpt Guingret, a daring man,

formed a small raft to hold their arms and clothes, and plunged into the water, holding their swords with their teeth,

swimming and pushing their raft before them. Under protection of a cannonande they crossed this

great river, though it was in full and strong water, and the weather very cold, and having reached the other side,

naked as they were, stormed the tower: the Brunswick regiment then abandoned the wood, and the gallant Frenchmen

remained masters of the bridge." (Napier - "History of the War ..."

Vol IV, p 138)

Picture: "the French arrived [at Tordesillas], 60

... headed by Cpt Guingret, a daring man,

formed a small raft to hold their arms and clothes, and plunged into the water, holding their swords with their teeth,

swimming and pushing their raft before them. Under protection of a cannonande they crossed this

great river, though it was in full and strong water, and the weather very cold, and having reached the other side,

naked as they were, stormed the tower: the Brunswick regiment then abandoned the wood, and the gallant Frenchmen

remained masters of the bridge." (Napier - "History of the War ..."

Vol IV, p 138)

Many napoleonic battles were very bloody and cost many lives.

In 1812 after the battle of Valutina Gora

"Gudin's division were drawn up on top of their companions' and Russian corpses, amidst half-broken trees, on ground

ripped up by roundshot ... Gudin's battalions were no longer more than platoons. All around was the smell of powder.

The Emperor couldn't pass along their front without having to avoid corpses, step over them or push them aside.

He was lavish with rewards. The 12th, 21st and 127th Line and the 7th Light received 87 decorations

and promotions." (Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 214)

Many napoleonic battles were very bloody and cost many lives.

In 1812 after the battle of Valutina Gora

"Gudin's division were drawn up on top of their companions' and Russian corpses, amidst half-broken trees, on ground

ripped up by roundshot ... Gudin's battalions were no longer more than platoons. All around was the smell of powder.

The Emperor couldn't pass along their front without having to avoid corpses, step over them or push them aside.

He was lavish with rewards. The 12th, 21st and 127th Line and the 7th Light received 87 decorations

and promotions." (Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 214)

In 1812 majority of veterans was swallowed up in the bloody battles and the

snows of Russia. The casualties were horrible and it required a heart of stone to

look on those gallant men, mangled, frozen and torn,

and heaped in thousands over the fields and roads.

In 1812 majority of veterans was swallowed up in the bloody battles and the

snows of Russia. The casualties were horrible and it required a heart of stone to

look on those gallant men, mangled, frozen and torn,

and heaped in thousands over the fields and roads.

In 1813 at Leipzig the defense of Probstheida was incredible. Digby-Smith writes: "The courage

and ferocity shown by both sides in the battle of Probstheida was truly unique, as were the losses they suffered.

An attempt by the Old Guard to advance south, however, was stopped by the Allied artillery on the low hill about 500 m away.

Generals Baillot, Montgenet and Rochambeau were all killed during the fighting here, while

French regiments which especially distinguished themselves were the 2nd, 4th and 18th Line and the 11th Light.

Even Prinz August von Preussen wrote most flatteringly of the enemy's valour ..."

In 1813 at Leipzig the defense of Probstheida was incredible. Digby-Smith writes: "The courage

and ferocity shown by both sides in the battle of Probstheida was truly unique, as were the losses they suffered.

An attempt by the Old Guard to advance south, however, was stopped by the Allied artillery on the low hill about 500 m away.

Generals Baillot, Montgenet and Rochambeau were all killed during the fighting here, while

French regiments which especially distinguished themselves were the 2nd, 4th and 18th Line and the 11th Light.

Even Prinz August von Preussen wrote most flatteringly of the enemy's valour ..."

Napoleonic infantryman was easy everywhere, little or nothing

worried him, neither the pyramids of Egypt nor the vast plains of snowy Russia.

No matter where he found himself, he considered himself

to be a representative of the French way of life.

The army will never forget that under Napoleon's eagles, deserving men of courage

and intelligence were raised to the highest levels of society.

Simple soldiers became marshals, princes, dukes and kings. The French soldier had become

an equal citizen by right and by glory.

Every soldier of Roman Empire could make a career in the army.

The veterans could even aspire to become

Napoleonic infantryman was easy everywhere, little or nothing

worried him, neither the pyramids of Egypt nor the vast plains of snowy Russia.

No matter where he found himself, he considered himself

to be a representative of the French way of life.

The army will never forget that under Napoleon's eagles, deserving men of courage

and intelligence were raised to the highest levels of society.

Simple soldiers became marshals, princes, dukes and kings. The French soldier had become

an equal citizen by right and by glory.

Every soldier of Roman Empire could make a career in the army.

The veterans could even aspire to become  The French infantrymen were not angels and sometimes behaved badly.

"The 43rd regiment of line infantry had ... became involved

in so many duels that the active enmity of the citizens [of Caen]

compelled its retirement." ( Parquin - "Napoleon's Victories")

The French infantrymen were not angels and sometimes behaved badly.

"The 43rd regiment of line infantry had ... became involved

in so many duels that the active enmity of the citizens [of Caen]

compelled its retirement." ( Parquin - "Napoleon's Victories")

Among the French troops occupying Spain looting was rampant, discipline was poor.

The veterans were demoralized by plunder and waste and by the cruel war with Spanish

guerillas. They had got out of the habit of being inspected. Training had fallen off during

the years. Several hundred of veterans were selected from the troops in Spain and sent to join the

Middle Guard. Although they looked good with tanned faces, some of them went around and

stole things in Paris. General Michel arrested them and sent to prisons.

Among the French troops occupying Spain looting was rampant, discipline was poor.

The veterans were demoralized by plunder and waste and by the cruel war with Spanish

guerillas. They had got out of the habit of being inspected. Training had fallen off during

the years. Several hundred of veterans were selected from the troops in Spain and sent to join the

Middle Guard. Although they looked good with tanned faces, some of them went around and

stole things in Paris. General Michel arrested them and sent to prisons.

The numerous campaigns made the military service unpopular in France. In 1813 in the west of

France it became necessary to hunt up the refractaires with mobile columns, and the generals reported that they were

afraid to use their young sldiers for this purpose.

The new army was huge but the 18- and 19-years old soldiers lacked stamina and the rapid

marches and hunger weakened them physically. Camille Rousset gives the following as a common type of report

on inspection: "Some of the men are of rather weak appearance. The battalion had no idea of manouveruring; but 9/10

of the men can manage and load their muskets passably." General Lambardiere writes: "These battalions arrive fatigued, every day

I supply them with special carriage for the weak and lame ... All these battalions are French; I must say that the young soldiers

show courage and good-will. Every possible moment is utilised in teaching them to load their arms and bring them

to the shoulder." So poor were they in physique that the Minister of Police protests against their being drilled

in the Champs Elysees during the hour of promenade, on account of the scoffing and jeering they gave rise to.

The numerous campaigns made the military service unpopular in France. In 1813 in the west of

France it became necessary to hunt up the refractaires with mobile columns, and the generals reported that they were

afraid to use their young sldiers for this purpose.

The new army was huge but the 18- and 19-years old soldiers lacked stamina and the rapid

marches and hunger weakened them physically. Camille Rousset gives the following as a common type of report

on inspection: "Some of the men are of rather weak appearance. The battalion had no idea of manouveruring; but 9/10

of the men can manage and load their muskets passably." General Lambardiere writes: "These battalions arrive fatigued, every day

I supply them with special carriage for the weak and lame ... All these battalions are French; I must say that the young soldiers

show courage and good-will. Every possible moment is utilised in teaching them to load their arms and bring them

to the shoulder." So poor were they in physique that the Minister of Police protests against their being drilled

in the Champs Elysees during the hour of promenade, on account of the scoffing and jeering they gave rise to.

The total strength of the French infantry under Napoleon varied.

In the beginning of Napoleon's reign, France had 90

line and 26 light regiments. In 1813-1814 it reached 137 line (numbered 1st-157th)

and 35 light (numbered 1st-37th) regiments.

Only in 1815 (Waterloo Campaign) the strength of French infantry fell below

the initial numbers and totaled: 90 line and 15 light regiments.

The total strength of the French infantry under Napoleon varied.

In the beginning of Napoleon's reign, France had 90

line and 26 light regiments. In 1813-1814 it reached 137 line (numbered 1st-157th)

and 35 light (numbered 1st-37th) regiments.

Only in 1815 (Waterloo Campaign) the strength of French infantry fell below

the initial numbers and totaled: 90 line and 15 light regiments.

The number of line regiments was almost identical with the number of departements in France.

In 1790 France had been reorganized into 83 Departments of similar size and each was

subdivided into 4-5 parts. Each Department had to furnish 4-5 battalions of line infantry to the Revolutionary Armies.

The number of line regiments was almost identical with the number of departements in France.

In 1790 France had been reorganized into 83 Departments of similar size and each was

subdivided into 4-5 parts. Each Department had to furnish 4-5 battalions of line infantry to the Revolutionary Armies.

There were two types of infantry, line and light. Both were able to execute all maneuvers,

incl. skirmishing. (Each company of infantry was divided into 2 sections, but when skirmishing it was divided

into 3 sections: left, right and center. The skirmishers of the left and right section

had their bayonets removed when on the skirmish line. Only the center section had their

bayonets fixed. Their primary target were enemy's officers, gunners, and skirmishers.)

There were two types of infantry, line and light. Both were able to execute all maneuvers,

incl. skirmishing. (Each company of infantry was divided into 2 sections, but when skirmishing it was divided

into 3 sections: left, right and center. The skirmishers of the left and right section

had their bayonets removed when on the skirmish line. Only the center section had their

bayonets fixed. Their primary target were enemy's officers, gunners, and skirmishers.)

The muskets were muzzleloading and smoothbore. But, primitive as they appear today, such weapons deserve respect.

John Elting writes: "In their own time they made and broke empires; they won, and nailed down, the independence

of the USA. Together with the Roman short sword and the Mongol composite bow, they rank as

the greatest man-killers of all-history. ...

The muskets were muzzleloading and smoothbore. But, primitive as they appear today, such weapons deserve respect.

John Elting writes: "In their own time they made and broke empires; they won, and nailed down, the independence

of the USA. Together with the Roman short sword and the Mongol composite bow, they rank as

the greatest man-killers of all-history. ...

The infantryman also carried bayonet.

"The earliest French bayonet attack occured no later than 1677 at the siege of Valenciennes,

where, after an enemy cavalry charge 'the musketeers, having put their bayonets in their

fusils, marched at them and with grenades and bayonets, chased them back in the town.'

In another use of the plug bayonet, dragoons beat back enemy forces at a river near the same

town in 1684. ... As they have so often in their history, the French pictured themselves as particularly

apt in the assault with cold steel. A belief in a special French talent in combat

a l'arme blanche probably goes back as far as Merovingian times. The cult of

the bayonet peaked late in the 18th century and again, with tragic consequences, just

prior to World War I. Much of the language later assumed by advocates of the bayonet was

already current in the 17th century. Writing in 1652, Laon expressed the belief that

'French infantry is more suited to the attack than to the defense.'

The French never seemed to tire of contrasting their own energy in the assault versus their

enemies' stolid nature, particularly when Germans were involved.

'The [German] infantry is constant enough when syanding fast, but it is not lively in the

attack and cannot carry off a coup de main. Chamlay agreed in the superiority of

the French infantry on the offensive, starting in 1690 ... The same confidence typified

opinion in the War of the Spanish Succession ... No less a figure than Marshal Villars

praised 'the air of audacity so natural for the French infantry ... is to charge with the

bayonet ..." (Lynn - "Giant of the Grand Siecle" pp 487-488)

The infantryman also carried bayonet.

"The earliest French bayonet attack occured no later than 1677 at the siege of Valenciennes,

where, after an enemy cavalry charge 'the musketeers, having put their bayonets in their

fusils, marched at them and with grenades and bayonets, chased them back in the town.'

In another use of the plug bayonet, dragoons beat back enemy forces at a river near the same

town in 1684. ... As they have so often in their history, the French pictured themselves as particularly

apt in the assault with cold steel. A belief in a special French talent in combat

a l'arme blanche probably goes back as far as Merovingian times. The cult of

the bayonet peaked late in the 18th century and again, with tragic consequences, just

prior to World War I. Much of the language later assumed by advocates of the bayonet was

already current in the 17th century. Writing in 1652, Laon expressed the belief that

'French infantry is more suited to the attack than to the defense.'

The French never seemed to tire of contrasting their own energy in the assault versus their

enemies' stolid nature, particularly when Germans were involved.

'The [German] infantry is constant enough when syanding fast, but it is not lively in the

attack and cannot carry off a coup de main. Chamlay agreed in the superiority of

the French infantry on the offensive, starting in 1690 ... The same confidence typified

opinion in the War of the Spanish Succession ... No less a figure than Marshal Villars

praised 'the air of audacity so natural for the French infantry ... is to charge with the

bayonet ..." (Lynn - "Giant of the Grand Siecle" pp 487-488)

The basic building block of napoleonic army organization was the individual soldier.

A small group of soldiers organized to maneuver and fire were section and platoon. As elements of the army’s organizational structure

become larger units, they contain more and more elements. A company was the smallest element to be given a designation

and affiliation with higher headquarters at battalion, regimental, brigade, and division level.

The basic building block of napoleonic army organization was the individual soldier.

A small group of soldiers organized to maneuver and fire were section and platoon. As elements of the army’s organizational structure

become larger units, they contain more and more elements. A company was the smallest element to be given a designation

and affiliation with higher headquarters at battalion, regimental, brigade, and division level.

The company was an administrative unit, the tactical unit was the platoon (peloton).

In 1808-1815 each company consisted of 140 men:

The company was an administrative unit, the tactical unit was the platoon (peloton).

In 1808-1815 each company consisted of 140 men: Just as modern company commander relies on his radio operator, his Napoleonic counterpart

depended on his drummers and cornets. During a battle it was very noisy and not everyone could hear

a officer's voice. For this reason every company had drummers and cornets.

They also performed a service that went beyond supplying a rhythmic musical accompaniment to the

marching infantry. The musicians carried wounded officers out of danger zone and after battle

stacking their drums, they would await the grim task of carrying their stricken comrades to field

hospitals.

Just as modern company commander relies on his radio operator, his Napoleonic counterpart

depended on his drummers and cornets. During a battle it was very noisy and not everyone could hear

a officer's voice. For this reason every company had drummers and cornets.

They also performed a service that went beyond supplying a rhythmic musical accompaniment to the

marching infantry. The musicians carried wounded officers out of danger zone and after battle

stacking their drums, they would await the grim task of carrying their stricken comrades to field

hospitals.

Each battalion had 1 corporal sapper and 4 privates sappers. These strong men with facial

hair marched together with regimental band and near the Eagle/flag.

Each battalion had 1 corporal sapper and 4 privates sappers. These strong men with facial

hair marched together with regimental band and near the Eagle/flag.

In 1805 approx. 1/3 were veterans of at least 6 years' service.

Thearmy of 1812 was almost as good as the famous Grand Army of 1805-1806. In 1812 however

there were less veterans in the ranks.

According to de Segur the old-timers could easily be recognized "by their martial air. Nothing could shake them.

They had no other memories, no other future, except warfare. They never spoke of anything else. Their officers

were either worthy of them or became it. For to exert one's rank over such men one had to be able to show them

one's wounds and cite oneself as an example." They stimulated the new recruits with their warlike tales, so that the

conscripts brightened up. By so often exaggerating their own feats of arms, the veterans obliged themselves to authenticate

by their conduct what they've led others to believe of them.

In 1805 approx. 1/3 were veterans of at least 6 years' service.

Thearmy of 1812 was almost as good as the famous Grand Army of 1805-1806. In 1812 however

there were less veterans in the ranks.

According to de Segur the old-timers could easily be recognized "by their martial air. Nothing could shake them.

They had no other memories, no other future, except warfare. They never spoke of anything else. Their officers

were either worthy of them or became it. For to exert one's rank over such men one had to be able to show them

one's wounds and cite oneself as an example." They stimulated the new recruits with their warlike tales, so that the

conscripts brightened up. By so often exaggerating their own feats of arms, the veterans obliged themselves to authenticate

by their conduct what they've led others to believe of them.

The bearskin was more difficult to cut through than shako and had better padding than the helmet. But it was quite expensive

and a black waxed cloth was used as protection against bad weather.

In July 1805 the carabiniers were ordered to return their bearskins to regimental depots in preparation "for the coming

campaign" and adopt shakos instead. In 1811 only few carabiniers and grenadiers retained their bearskins, most wore shakos.

In February 1812 the fur caps were officially discontinued in grenadiers and carabiniers due to shortage of bear skins.

Grenadiers' shako had red shevrons and bands.

The bearskin was more difficult to cut through than shako and had better padding than the helmet. But it was quite expensive

and a black waxed cloth was used as protection against bad weather.

In July 1805 the carabiniers were ordered to return their bearskins to regimental depots in preparation "for the coming

campaign" and adopt shakos instead. In 1811 only few carabiniers and grenadiers retained their bearskins, most wore shakos.

In February 1812 the fur caps were officially discontinued in grenadiers and carabiniers due to shortage of bear skins.

Grenadiers' shako had red shevrons and bands.

Each war battalion had only 1 grenadier and 1 voltigeur company, the remaining 4-8

companies were made of fusiliers (chasseurs in light infantry).

The fusiliers (chasseurs) occupied the center of battalion line

and for this reason were called centre companies.

Each war battalion had only 1 grenadier and 1 voltigeur company, the remaining 4-8

companies were made of fusiliers (chasseurs in light infantry).

The fusiliers (chasseurs) occupied the center of battalion line

and for this reason were called centre companies.

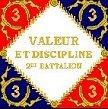

"A month after being proclaimed Emperor in May 1804, Napoleon decided on the emblem of Empire.

He considered the cock and the lion but rejected both in favour of an eagle with wings

spread. It became the design of the Great Seal of State and the emblem of the army and navy.

In the army the Eagle would be carried on top of a pole with a standard underneath.

The Eagle was the supreme importance. When writing on the subject to Marechal Berthier

he stressed that it was the priceless symbol of France and the Empire, while the standard

below it was of lesser importance and could be replaced if necessary. ...

Because the Consular Guard, and then the Imperial Grenadier and Chasseur Guard regiments, were normally

in barracks in Paris or on palace duties, their Eagles were kept in a room next to the

throne room in the Tuileries." (Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 200)

"A month after being proclaimed Emperor in May 1804, Napoleon decided on the emblem of Empire.

He considered the cock and the lion but rejected both in favour of an eagle with wings

spread. It became the design of the Great Seal of State and the emblem of the army and navy.

In the army the Eagle would be carried on top of a pole with a standard underneath.

The Eagle was the supreme importance. When writing on the subject to Marechal Berthier

he stressed that it was the priceless symbol of France and the Empire, while the standard

below it was of lesser importance and could be replaced if necessary. ...

Because the Consular Guard, and then the Imperial Grenadier and Chasseur Guard regiments, were normally

in barracks in Paris or on palace duties, their Eagles were kept in a room next to the

throne room in the Tuileries." (Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 200)

The Eagle was with the 2nd Company of 1st Battalion.

The Eagle was with the 2nd Company of 1st Battalion.  The flag of 1815 was also a tri-color pattern but it lacked almost all the magnificent embroidery of 1804 pattern. After Waterloo the Bourbons did their best to see that all the napoleonic standards and eagles were destroyed. In some regiments the officers burned the standards before mixing the ashes with wine and drinking them down. The officers of the 2nd Swiss Regiment in napoleonic army, tore their standard into strips with each officer keeping a piece.

The flag of 1815 was also a tri-color pattern but it lacked almost all the magnificent embroidery of 1804 pattern. After Waterloo the Bourbons did their best to see that all the napoleonic standards and eagles were destroyed. In some regiments the officers burned the standards before mixing the ashes with wine and drinking them down. The officers of the 2nd Swiss Regiment in napoleonic army, tore their standard into strips with each officer keeping a piece.

The French army contained many regiments of line and light infantry whose

soldierly skills and deeds of daring reflected the unsurpassed devotion of the soldiers

to their cause and to Napoleon.

They all won immortal fame in those ten

terrible years of strife.

The French army contained many regiments of line and light infantry whose

soldierly skills and deeds of daring reflected the unsurpassed devotion of the soldiers

to their cause and to Napoleon.

They all won immortal fame in those ten

terrible years of strife.