|

.

"If the French had the firmness

and the docility of the Russians

the world would not be great enough for me."

- Emperor Napoleon

|

Brief History of Russian Empire and Army.

"Russia, as much by her position

as by her inexhaustible resources,

is and must be the first power in the world."

- Russian Chancellor Rostopchin

During the XVIII and XIX century Russia's diplomats and army made it one of the most

powerful states in the world. Catherine the Great worked hard at organising the state,

involved herself in the affairs of Europe, and initiated an aggressive foreign policy

which over few decades was to add the whole of Finland, (ext.link) what are now Estonia, Latvia,

Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, (ext.link) most of Poland, the Crimea, some of what is now Romania,

the Kuban, Georgia, Kabardia, Azerbaidijan, part of Siberia and Kamchatka to her

dominions, as well as part of Alaska (ext.link) and a military settlement north of San

Francisco (ext.link).

During the XVIII and XIX century Russia's diplomats and army made it one of the most

powerful states in the world. Catherine the Great worked hard at organising the state,

involved herself in the affairs of Europe, and initiated an aggressive foreign policy

which over few decades was to add the whole of Finland, (ext.link) what are now Estonia, Latvia,

Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, (ext.link) most of Poland, the Crimea, some of what is now Romania,

the Kuban, Georgia, Kabardia, Azerbaidijan, part of Siberia and Kamchatka to her

dominions, as well as part of Alaska (ext.link) and a military settlement north of San

Francisco (ext.link).

"This not only increased the size of Russia, it also brought her frontiers 600 km further into Europe... By 1799

Russian armies were operating in Switzerland and Italy."

(Zamoyski - "Moscow 1812" p 17)

Russian Chancellor Rostopchin wrote:

"Russia, as much by her position as by her inexhaustible resources, is and must be the

first power in the world." Many in Europe were alarmed at this seemingly inexorable onward

march of Russian power. There was talk of ravening Asiatic hordes and some fear, that

Russia might engulf the whole of Europe as the barbarians had done with ancient Rome.

When Revolution in France erupted Russia promised that the rule of mobs in France would soon

end and true order of matters would be restored. Russian aristocrats were shocked when the

citizens in France proclaimed "liberté, egalité, fraternité" and the country of high culture,

the language of which was spoken in salons from Madrid and London to Berlin, Warsaw, Vienna

and Rome found itself in the hands of the revolutionaries. This drew Russia into a series of wars against France and her neighbors,

which had far-reaching consequences for Europe.

Russia was torn between Asia and Europe and only sparsely settled.

The vast land together with the long winters produced the melancholy and mystery not felt

in any other country.

According to Paul Austin when in 1812 Napoleon's army entered Russia, the troops were

"a bit frightened at the sight of so sparsely populated and poverty-stricken a countryside.

Dedem finds himself in 'a desert' ... Bonnet of the 18th Line, Ney's III Corps ...

is shocked to see how the peasants' clothing consists of only "a shirt, a pair of coarse

cloth trousers, a hooded cloak of sheepskin and some kind of a fur cap." ...

As for their villages, they're even more squalid than the Polish ones.

... General Claparede, writes home to his young bride: 'The inhabitants and their houses

are very ugly and extremely dirty, and the latter only differ from the peasants' log cabins

in possessing a chimney or two.' ... Although General Compans, commanding Davout's crack

5th Division, is finding the countryside 'quite attractive' ..."

(Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 59)

The city of Vitebsk made poor impression on the French "From the outside the houses,

all higgledy-piggledy, small, low and built of wood, have the most wretched appearance"

according to General Berthezene.

But the road to Moscow is a masterpiece - according to Captain Breaut des Marlots

"you can march along in 10 vehicles abreast." Moscow made impression on the enemy:

"The sun was reflected on all the domes, the spires and gilded palaces.

The many capitals I'd seen - such as Paris, Berlin, Warsaw, Vienna and Madrid -

had only produced an ordinary impression on me. But this was quite different !"

- wrote Bourgogne. Griois writes: "In no way did it resemble any cities

I'd seen in Europe."

Moscow and St.Petersburg were the largest Russian cities.

St.Petersburg was a planned city of canals and straight streets, reflecting the rationalizm

of Peter the Great.

Moscow and St.Petersburg were the largest Russian cities.

St.Petersburg was a planned city of canals and straight streets, reflecting the rationalizm

of Peter the Great.

By contrast, Moscow had grown more spontaneously, and its many large gardens and old churches

made it seem more rural, religious, and 'Russian' than St.Petersburg.

Richard Rhein writes: "Moscow in 1812 was a sprawling city of about 250,000 inhabitants

during the fall. Throughout the winter months, when the nobles and their serfs returned from their country estates,

the populationwould increase by about 100,000."

The inhabitants of St.Petersburg were more open to foreign ideas

and less slothful and superstitious than those of Moscow.

Serfdom was not the original status of the Russian peasant.

It was one of the consequences of the Tartar devastation during the 13th century

when peasants became homeless and settled on the land of wealthy Russians.

By the end of the 16th century the Russian peasant came under the complete control of

the landowner and during the middle of the 17th century serfdom became hereditary. Their

situation became comparable to that of slaves in USA and they could be sold to another

landowner in families or singly.

By the 19th century it was estimated that about 50 per cent of Russian peasants were serfs.

Willian Napier calls it "the most formidable and brutal, the most swinish tyranny that has

ever menaced and disgraced European civilization."

(Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814" Vol IV, p 167)

By the 19th century it was estimated that about 50 per cent of Russian peasants were serfs.

Willian Napier calls it "the most formidable and brutal, the most swinish tyranny that has

ever menaced and disgraced European civilization."

(Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814" Vol IV, p 167)

The peasants and serfs were engaged in agricultural work on fields and farms and with

herding the livestock. From May through October they commonly worked barefoot.

In colder times they had their feet wrapped in clothes over which was fitted

a basketwork affair. They wore rough shirts and trousers made from canvas and often

slept on straw or dry hay.

By 1800, the nobles of the empire made up more than 2 % of the population.

The nobles measured their wealth primarily by the number of male serfs they owned.

Most young nobles were forced by economic need to serve in the military.

From Mongol Yoke to the "Time of Troubles."

Polish troops captured Moscow in 1610.

The invading Mongols accelerated the fragmentation of the Ancient Rus'.

Although a Russian army defeated the Golden Horde at Kulikovo Pole in 1380, Tatar

domination of the Russian-inhabited territories, along with demands of tribute from

Russian princes, continued until about 1480.

The invading Mongols accelerated the fragmentation of the Ancient Rus'.

Although a Russian army defeated the Golden Horde at Kulikovo Pole in 1380, Tatar

domination of the Russian-inhabited territories, along with demands of tribute from

Russian princes, continued until about 1480.

Ivan IV, the Terrible, (ext.link) first Muscovite tsar, is considered to have founded the Russian state.

Death of Ivan's childless son Feodor I was followed by a period of civil wars and foreign intervention known as the

Time of Troubles. It was a period of Russian history comprising the years o interregnum between the death of the last of

Moscow Rurukids Dynasty, Tsar Feodor I, in 1598 and the establishment of the Romanov Dynasty in 1613.

The succession disputes during the Time of Troubles caused the loss of much territory to the

Poles and Swedes.

In the battle of Orsha 25.000 Poles and Lithuanians routed 40,000-80,000 Russians with 300

guns.

In 1610 in Klushino 7,000 Poles mauled 40,000 Russians and Allies. Muscovy lost control over western territories and even

Moscow itself was captured by Polish troops in 1610.

(ext.link)

The Time of Troubles was brought to an end when a patriotic volunteer army expelled the Poles

from the Moscow Kremlin and anational assembly, elected to the throne

Michael Romanov. The Romanov Dynasty ruled Russia until 1917.

Peter the Great and "Progress Through Coercion."

One new item after another was taxed, from beards to watermelons.

Most revenue went for military needs, for as Peter stated:

"Money is the artery of war."

Tzar Peter the Great achieved Russia's expansion and its transformation into the

Russian Empire through several major initiatives.

He established Russia's naval forces, reorganized the army according to European models,

streamlined the government, and mobilized Russia's financial and human resources.

Tzar Peter the Great achieved Russia's expansion and its transformation into the

Russian Empire through several major initiatives.

He established Russia's naval forces, reorganized the army according to European models,

streamlined the government, and mobilized Russia's financial and human resources.

The army was new and huge.

By 1725, Russia had an army of about 200,000 regular troops

and about 100,000 Cossacks. Army recruits were sometimes chained together on

their way to military service. Beginning in 1712, recruits were branded on their left arms,

thereby facilitating the apprehension of runaways.

By the time of his death in 1725 Peter the Great had placed Russia among the foremost European powers,

and had created a military system that has infuenced the European balance of power until the present day.

The reformed Russian army won a major victory at Poltava and have anded Sweden's role as a Great Power.

It the most famous of the battles of the Great Northern War (45,000 Russians defeated 17,000 Swedes

+ 8,000 sieging Poltava). Several thousand prisoners were were put to work building the new city of St. Petersburg.

Swedish King Charles managed to escape and spent five years in exile there before he was able

to return to Sweden.

Palace Coups.

Peter III changed the army's uniform

to look like Prussia's,

insulting the soldiers greatly

The third of a century between the reigns of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great was

an era of palace coups, court favorites, heightened noble privileges, and several distinctly

nongreat monarchs. During the rule of Peter's successors, Russia took a more active role in European statecraft.

Russia's greatest reach into Europe was during the Seven Years' War.

In 1760 Russian forces were at the gates of Berlin. Fortunately for Prussia, Russian

monarch Elizabeth died and her successor, Peter III, allied Russia with Prussia.

Although he was tolerant of Catherine the Great's marital indiscretions, he was little

worried about bastard children eventually following in his footsteps to the Russian throne.

At one point, he exclaimed, "God knows where my wife gets her pregnancies!" :-))

Although he was a grandson of Peter the Great, his father was the duke of Holstein-Gottorp,

so Peter III was raised in a German environment. Russians therefore considered him a

foreigner. Making no secret of his contempt for all things Russian,

he went so far as to have a ring made with a picture of Prussian king Frederick the Great

set in it which Troyat claims, "he would kiss fervently at

every opportunity."

Peter III changed the army's uniform to look like Prussia's, insulting the

soldiers greatly - the Russian army had been fighting the Prussians for almost a decade,

and were fairly indignant about suddenly having to look like them: "The hearts of the greater

number of them were filled with grief, and with hatred and contempt for their future Emperor."

Russia and the army under Tzar Paul.

Paul ordered more than 20,000 Cossacks

to cross Central Asia and invade British India.

Tzar Paul was determined that the soldiers should be treated well.

The monarch increased the pay for ordinary soldier and intended to curb the drunkenness of the officers, their gambling

and the frauds they perpetrated at the expense of the soldiers.

The monarch dismissed 340 generals and 2,261 officers.

Approx. 3,500 officers resigned.

Tzar Paul was determined that the soldiers should be treated well.

The monarch increased the pay for ordinary soldier and intended to curb the drunkenness of the officers, their gambling

and the frauds they perpetrated at the expense of the soldiers.

The monarch dismissed 340 generals and 2,261 officers.

Approx. 3,500 officers resigned.

Tzar Paul however failed to grasp the difference between mechanical drills amd what was

really practicable in combat. In 1796-98 were issued 'The Infantry Codes.'

General Suvorov dismissed them as a rat-chewed package found in a castle and made no attempt

to enforce them among his troops.

Polish revolutionary leader Tedd Kosciuszko fought the Russian on several occassions,

and wrote: "When they are on the offensive they are fortified by copious distributions

of alcohol, and they attack with a courage which verges on a frenzy, and would rather get

killed than fall back. The only way to make them desist is to kill a great number of their

officers ...The Russian infantry withstand fire fearlessly, but their own

fire is badly directed ... they are machines which are actuated only by the orders of

their officers."

"Paul hated revolutionary France and feared its advances in the eastern Mediterranean.

... Russian forces fought on both land and sea. Most notable were Gedneral Suvorov's

victories against the French in Italy and Switzerland. ... But discord among coalition members

led to Russia's withdrawal from the Second Coalition in 1799. ... Hoping, with Napoleon's backing, to gain

Constantinopole and Balkan territories, Paul agreed to support France against England.

Shortly before his overthrow, Paul ordered more than 20,000 Cossacks to cross Central

Asia and invade British India." (Moss - "A History of Russia" Vol I, pp 338-9)

General Alexander Suvorov.

He was reckoned one of a few generals in history

who never lost a single battle.

ARTICLE >>

Russia against Napoleonic France.

As a major European power, Russia could not escape the wars

involving revolutionary and imperial France.

Russia during the Napoleonic Wars was ruled by Tsar Alexander I.

He succeeded to the throne after his father was murdered. Young Alexander sympathised with

French and Polish revolutionaries (Kosciuszko Uprising), however, his father seems to have taught him to combine a

theoretical love of mankind with a practical contempt for men. These contradictory tendencies remained with him through life

and are observed in his dualism in domestic and military and foreign policy.

Russia during the Napoleonic Wars was ruled by Tsar Alexander I.

He succeeded to the throne after his father was murdered. Young Alexander sympathised with

French and Polish revolutionaries (Kosciuszko Uprising), however, his father seems to have taught him to combine a

theoretical love of mankind with a practical contempt for men. These contradictory tendencies remained with him through life

and are observed in his dualism in domestic and military and foreign policy.

Napoleon thought him a "shifty Byzantine".

Castlereagh of Britain gives him credit for "grand qualities", but adds that he is "suspicious and undecided". Alexander however

was the most influential person in Allies headquarters in 1813-1814.

The first ten years of Alexander's reign witnessed even longer periods of war in

the south against Persia, Caucassian peoples and especially against Turkey.

As a major European power, Russia could not escape the wars involving revolutionary

and imperial France.

These campaigns began in late 1790s and ended in 1814-1815 and were ones of the most intensive

fightings in Russia's history. It was a long and rocky period with many changes in the army.

When Tzar Alexander came to power he halted the germanization of the army and in 1802

many Prussian distinctions were abolished.

Fearing expansionist ambitions of Napoleon, Alexander joined Great Britain and Austria against Napoleon.

Meanwhile mutual suspicion between Great Britain and Rusia eased in the face of several French political mistakes.

Fearing expansionist ambitions of Napoleon, Alexander joined Great Britain and Austria against Napoleon.

Meanwhile mutual suspicion between Great Britain and Rusia eased in the face of several French political mistakes.

In 1805 Britain and Russia signed an offensive alliance directed against France.

They were joined by Austria and Sweden.

The Orthodox Church in Russia designated “ Napoleon as the anti-christ and the enemy of God

for having founded a new Hebrew Sanhedrin, which is the same tribunal that once dared to condemn the

Lord Jesus to the cross.”

The Russian army had many characteristics of ancien regime, senior officers were largely recruited from

aristocratic circles, and the Russian soldier was regularly beaten and punished to instill discipline.

Furthermore, many lower-level officers were poorly trained.

Austrian army invaded and occupied Bavaria; French troops crossed the Rhine River.

Napoleon defeated the Austrians at Ulm and then occupied Vienna.

In December Napoleon decisively defeated an Austro-Russian army in the battle of Austerlitz.

In 1806 the outdated system of dividing the army into columns and brigades of various strength

was abandoned. Also most of the inspections were abolished and replaced by numbered divisions.

In 1806 the outdated system of dividing the army into columns and brigades of various strength

was abandoned. Also most of the inspections were abolished and replaced by numbered divisions.

Average division consisted of:

4-6 infantry regiments

2-4 cavalry regiments

Cossacks

strong artillery

In 1806, Prussia joined the Fourth Coalition fearing the rise in French power after the defeat of Austria.

Prussia and Russia mobilized for a fresh campaign.

After Napoleon’s humiliation of Prussia at Jena, the French Emperor turned his attention to subduing his

Russian foe and marched into Poland in the winter of 1806. Six months later, the Russians had been beaten in Eylau,

Heilsberg and Fredland and brought to the peace table and Napoleon was at the height of his power.

The French drove Russian forces out of Poland and created a new Duchy of Warsaw.

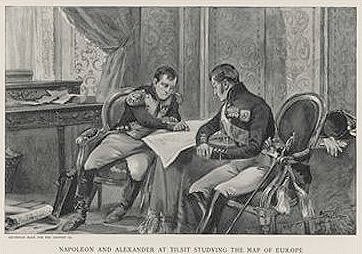

Few days after the battle of Friedland, Napoleon and Tzar Alexander met at Tilsit on a raft in the middle of the Nemunas.

The treaty ended war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires which rendered the rest

of Europe almost powerless. However, Napoleon's matrimonial plans to marry the tsar's sister were stymied by Russian royalty.

Few days after the battle of Friedland, Napoleon and Tzar Alexander met at Tilsit on a raft in the middle of the Nemunas.

The treaty ended war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires which rendered the rest

of Europe almost powerless. However, Napoleon's matrimonial plans to marry the tsar's sister were stymied by Russian royalty.

France and Russia secretly agreed to aid each other in disputes - France pledged to aid Russia against Turkey, while

Russia agreed to join the Continental System against Britain. Napoleon also convinced Alexander to instigate the Finnish

War against Sweden in order to force Sweden to join the Continental System. Russia agreed to evacuate Wallachia and

Moldavia, which had been occupied by Russian troops. The Ionian Islands, which had been captured by Russian navy,

were to be handed over to the French.

In 1810 General de Tolly introduced military attaches. These were military agents who collected information and

were attached to Russian political missions in Paris, Warsaw and Vienna.

In 1810 General de Tolly introduced military attaches. These were military agents who collected information and

were attached to Russian political missions in Paris, Warsaw and Vienna.

In 1810-1812 de Tolly, Volkonskii and others analyzed the French army, its organization,

structure and methods of combat. They introduced many changes, including brigades and divisions

with permanent structure and staff, infantry and cavalry corps etc.

The influence of modern military ideas from France was a gust of fresh air.

"Napoleon had many admirers in Russia particularly among the young - some of whom

would be drinking his health even after the war with France had began." (- Adam Zamoyski)

The Russo-French alliance gradually became strained. France was concerned about Russia's intentions in the strategically

vital Bosporus and Dardanelles straits. At the same time, Alexander viewed the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, the

French-controlled reconstituted Polish state, with suspicion. The requirement of joining France's Continental Blockade

against Great Britain was a serious disruption of Russian commerce, and in 1810 Alexander repudiated the obligation.

In June 1812, Napoleon invaded Russia with a force twice as large as the Russian

army facing him. He hoped to inflict a major defeat on the Russians and force

Alexandr to sue for peace.

Refusing to be cowed by the monstrous international army

on his borders, the Russian monarch made crystal clear to Napoleon’s messenger Narbonne:

“All Europe’s bayonets on my frontier won’t make me alter my language.”

Refusing to be cowed by the monstrous international army

on his borders, the Russian monarch made crystal clear to Napoleon’s messenger Narbonne:

“All Europe’s bayonets on my frontier won’t make me alter my language.”

Reformed Russian army performed well in 1812 and ended up as the

winners. By the way, many battles were fought with the

Russians being weaker in numbers than the French.

- Smolensk: French 50,000 - Russians 30,000

- Shevardino: French 30,000 - Russians 18,000

- Valutina Gora: French 42,000 - Russians 21,000

- Mohilev: French 27 000 - Russians 21 000

Article: Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, 1812

Generally the Russian victories in 1812-1815 are little known as the western authors

used mainly French sources. Only recently more balanced books were written.

The battles of Borisov, Jakubovo, Jonkovo, Krasnoi, Liakhovo, Mir, Romanov, Polotzk 2nd, Smoliany, Viazma (French losses 8,000 -

Russian losses 2,100), Vinkovo (French losses 3,600-4,000, Russian losses 500-1,800),

- these are Russian victories.

After the battle at Valutina Gora, Napoleon made remark that he likes when there are 3

enemy to 1 dead Frenchman. According to Gelder however, Marshal Murat "had the corpses

of the French dead stripped. He wanted to make Napoleon

believe all those he saw were Russians." (Austin - "1812: The March on Moscow")

In Vyazma, approx. 25,000 Russians defeated 35,000 French, Poles and Italians.

Kutuzov was unable to hold back his troops in their anxiety to catch up with the fleeing

French. Davout's highly trained I Army Corps was cut off from Napoleon's

army. Eugene's and Ney's corps and Poniatowski's Poles turned back to free Davout.

The fighting was hard. The French at the cost of 8,000 killed, wounded and prisoners

managed to break through. The Russians suffered only 2,100 casualties. Davout's corps

was rescued although was in total disarray. There is not a single book in the west devoted

to this battle.

In Vyazma, approx. 25,000 Russians defeated 35,000 French, Poles and Italians.

Kutuzov was unable to hold back his troops in their anxiety to catch up with the fleeing

French. Davout's highly trained I Army Corps was cut off from Napoleon's

army. Eugene's and Ney's corps and Poniatowski's Poles turned back to free Davout.

The fighting was hard. The French at the cost of 8,000 killed, wounded and prisoners

managed to break through. The Russians suffered only 2,100 casualties. Davout's corps

was rescued although was in total disarray. There is not a single book in the west devoted

to this battle.

In 1813 Russia had opened the campaign single-handed, and in which

was afterwards joined by Prussia and Austria. The driving and decisive force was the Russian army. Without it the Prussians wouldn't even dream to move their finger against Napoleon.

Witnesses described the King of Prussia as Tsar's aide-de-camp or lackey. Since 1815 the

Prussian uniform was modeled on Russian design as Russian military enjoyed great reputation

after the Napoleonic Wars. The Austrians were repeatedly beaten by Napoleon and were so well behaving that they even

supported Napoleon in 1812. Russian victory in 1812 encouraged them to stand up

and fight in 1813. Without Russia, the Austrians would be under French boot for long.

In 1813 Russia had opened the campaign single-handed, and in which

was afterwards joined by Prussia and Austria. The driving and decisive force was the Russian army. Without it the Prussians wouldn't even dream to move their finger against Napoleon.

Witnesses described the King of Prussia as Tsar's aide-de-camp or lackey. Since 1815 the

Prussian uniform was modeled on Russian design as Russian military enjoyed great reputation

after the Napoleonic Wars. The Austrians were repeatedly beaten by Napoleon and were so well behaving that they even

supported Napoleon in 1812. Russian victory in 1812 encouraged them to stand up

and fight in 1813. Without Russia, the Austrians would be under French boot for long.

Below: allied armies in the battle of Leipzig in 1813.

| |

infantry battalions |

cavalry squadrons |

Russian

Army |

215

|

234

|

Austrian

Army |

115

|

127

|

Prussian

Army |

110

|

121

|

|

The Tzar was determined to defeat Napoleon and 'liberate Europe'.

He said "I shall not make peace as long as Napoleon is on the throne." And so he did.

The Tzar was determined to defeat Napoleon and 'liberate Europe'.

He said "I shall not make peace as long as Napoleon is on the throne." And so he did.

In 1813 the Aliies defeated Napoleon's troops in Germany and again in 1814 in France.

Tzar Alexander triumphantly entered Paris and the Russians camped in front of Napoleon's

palace. Napoleon made remark: "The Russians learned [how to win]."

The wars were over and the period of nine consecutive campaigns in which

the Russian troops participated came to an end; Finland was captured,

Sweden was defeated, war with Turkey was won, Caucassus and Poland were taken,

Germany and Prussia were liberated, Paris captured and the mighty Napoleon was

crushed.

Battle of Heilsberg 1807 ~

Battle of Borodino 1812

Battle of Dresden 1813 ~

Battle of Leipzig 1813

Battle of La Rothiere 1814 ~

Battle of Paris 1814

|

During the XVIII and XIX century Russia's diplomats and army made it one of the most

powerful states in the world. Catherine the Great worked hard at organising the state,

involved herself in the affairs of Europe, and initiated an aggressive foreign policy

which over few decades was to add the whole of

During the XVIII and XIX century Russia's diplomats and army made it one of the most

powerful states in the world. Catherine the Great worked hard at organising the state,

involved herself in the affairs of Europe, and initiated an aggressive foreign policy

which over few decades was to add the whole of  Moscow and St.Petersburg were the largest Russian cities.

St.Petersburg was a planned city of canals and straight streets, reflecting the rationalizm

of Peter the Great.

Moscow and St.Petersburg were the largest Russian cities.

St.Petersburg was a planned city of canals and straight streets, reflecting the rationalizm

of Peter the Great.

By the 19th century it was estimated that about 50 per cent of Russian peasants were serfs.

Willian Napier calls it "the most formidable and brutal, the most swinish tyranny that has

ever menaced and disgraced European civilization."

(Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814" Vol IV, p 167)

By the 19th century it was estimated that about 50 per cent of Russian peasants were serfs.

Willian Napier calls it "the most formidable and brutal, the most swinish tyranny that has

ever menaced and disgraced European civilization."

(Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814" Vol IV, p 167)

The invading Mongols accelerated the fragmentation of the Ancient Rus'.

Although a Russian army defeated the Golden Horde at Kulikovo Pole in 1380, Tatar

domination of the Russian-inhabited territories, along with demands of tribute from

Russian princes, continued until about 1480.

The invading Mongols accelerated the fragmentation of the Ancient Rus'.

Although a Russian army defeated the Golden Horde at Kulikovo Pole in 1380, Tatar

domination of the Russian-inhabited territories, along with demands of tribute from

Russian princes, continued until about 1480.

Tzar Peter the Great achieved Russia's expansion and its transformation into the

Russian Empire through several major initiatives.

He established Russia's naval forces, reorganized the army according to European models,

streamlined the government, and mobilized Russia's financial and human resources.

Tzar Peter the Great achieved Russia's expansion and its transformation into the

Russian Empire through several major initiatives.

He established Russia's naval forces, reorganized the army according to European models,

streamlined the government, and mobilized Russia's financial and human resources.

Tzar Paul was determined that the soldiers should be treated well.

The monarch increased the pay for ordinary soldier and intended to curb the drunkenness of the officers, their gambling

and the frauds they perpetrated at the expense of the soldiers.

The monarch dismissed 340 generals and 2,261 officers.

Approx. 3,500 officers resigned.

Tzar Paul was determined that the soldiers should be treated well.

The monarch increased the pay for ordinary soldier and intended to curb the drunkenness of the officers, their gambling

and the frauds they perpetrated at the expense of the soldiers.

The monarch dismissed 340 generals and 2,261 officers.

Approx. 3,500 officers resigned.

Russia during the Napoleonic Wars was ruled by Tsar Alexander I.

He succeeded to the throne after his father was murdered. Young Alexander sympathised with

French and Polish revolutionaries (Kosciuszko Uprising), however, his father seems to have taught him to combine a

theoretical love of mankind with a practical contempt for men. These contradictory tendencies remained with him through life

and are observed in his dualism in domestic and military and foreign policy.

Russia during the Napoleonic Wars was ruled by Tsar Alexander I.

He succeeded to the throne after his father was murdered. Young Alexander sympathised with

French and Polish revolutionaries (Kosciuszko Uprising), however, his father seems to have taught him to combine a

theoretical love of mankind with a practical contempt for men. These contradictory tendencies remained with him through life

and are observed in his dualism in domestic and military and foreign policy.  Fearing expansionist ambitions of Napoleon, Alexander joined Great Britain and Austria against Napoleon.

Meanwhile mutual suspicion between Great Britain and Rusia eased in the face of several French political mistakes.

Fearing expansionist ambitions of Napoleon, Alexander joined Great Britain and Austria against Napoleon.

Meanwhile mutual suspicion between Great Britain and Rusia eased in the face of several French political mistakes.

In 1806 the outdated system of dividing the army into columns and brigades of various strength

was abandoned. Also most of the inspections were abolished and replaced by numbered divisions.

In 1806 the outdated system of dividing the army into columns and brigades of various strength

was abandoned. Also most of the inspections were abolished and replaced by numbered divisions.

Few days after the battle of Friedland, Napoleon and Tzar Alexander met at Tilsit on a raft in the middle of the Nemunas.

The treaty ended war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires which rendered the rest

of Europe almost powerless. However, Napoleon's matrimonial plans to marry the tsar's sister were stymied by Russian royalty.

Few days after the battle of Friedland, Napoleon and Tzar Alexander met at Tilsit on a raft in the middle of the Nemunas.

The treaty ended war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires which rendered the rest

of Europe almost powerless. However, Napoleon's matrimonial plans to marry the tsar's sister were stymied by Russian royalty.

In 1810 General de Tolly introduced military attaches. These were military agents who collected information and

were attached to Russian political missions in Paris, Warsaw and Vienna.

In 1810 General de Tolly introduced military attaches. These were military agents who collected information and

were attached to Russian political missions in Paris, Warsaw and Vienna.

Refusing to be cowed by the monstrous international army

on his borders, the Russian monarch made crystal clear to Napoleon’s messenger Narbonne:

“All Europe’s bayonets on my frontier won’t make me alter my language.”

Refusing to be cowed by the monstrous international army

on his borders, the Russian monarch made crystal clear to Napoleon’s messenger Narbonne:

“All Europe’s bayonets on my frontier won’t make me alter my language.”

In Vyazma, approx. 25,000 Russians defeated 35,000 French, Poles and Italians.

Kutuzov was unable to hold back his troops in their anxiety to catch up with the fleeing

French. Davout's highly trained I Army Corps was cut off from Napoleon's

army. Eugene's and Ney's corps and Poniatowski's Poles turned back to free Davout.

The fighting was hard. The French at the cost of 8,000 killed, wounded and prisoners

managed to break through. The Russians suffered only 2,100 casualties. Davout's corps

was rescued although was in total disarray. There is not a single book in the west devoted

to this battle.

In Vyazma, approx. 25,000 Russians defeated 35,000 French, Poles and Italians.

Kutuzov was unable to hold back his troops in their anxiety to catch up with the fleeing

French. Davout's highly trained I Army Corps was cut off from Napoleon's

army. Eugene's and Ney's corps and Poniatowski's Poles turned back to free Davout.

The fighting was hard. The French at the cost of 8,000 killed, wounded and prisoners

managed to break through. The Russians suffered only 2,100 casualties. Davout's corps

was rescued although was in total disarray. There is not a single book in the west devoted

to this battle.

In 1813 Russia had opened the campaign single-handed, and in which

was afterwards joined by Prussia and Austria. The driving and decisive force was the Russian army. Without it the Prussians wouldn't even dream to move their finger against Napoleon.

Witnesses described the King of Prussia as Tsar's aide-de-camp or lackey. Since 1815 the

Prussian uniform was modeled on Russian design as Russian military enjoyed great reputation

after the Napoleonic Wars. The Austrians were repeatedly beaten by Napoleon and were so well behaving that they even

supported Napoleon in 1812. Russian victory in 1812 encouraged them to stand up

and fight in 1813. Without Russia, the Austrians would be under French boot for long.

In 1813 Russia had opened the campaign single-handed, and in which

was afterwards joined by Prussia and Austria. The driving and decisive force was the Russian army. Without it the Prussians wouldn't even dream to move their finger against Napoleon.

Witnesses described the King of Prussia as Tsar's aide-de-camp or lackey. Since 1815 the

Prussian uniform was modeled on Russian design as Russian military enjoyed great reputation

after the Napoleonic Wars. The Austrians were repeatedly beaten by Napoleon and were so well behaving that they even

supported Napoleon in 1812. Russian victory in 1812 encouraged them to stand up

and fight in 1813. Without Russia, the Austrians would be under French boot for long.

The Tzar was determined to defeat Napoleon and 'liberate Europe'.

He said "I shall not make peace as long as Napoleon is on the throne." And so he did.

The Tzar was determined to defeat Napoleon and 'liberate Europe'.

He said "I shall not make peace as long as Napoleon is on the throne." And so he did.

Usually the privates drank water or whatever they found at civilians.

If a place was not healthy then instead of using local water they drunk diluted wine or

kvas and snacked on bread or suhary. Their officers drunk tea with rum, and in winter a better quality wine.

Usually the privates drank water or whatever they found at civilians.

If a place was not healthy then instead of using local water they drunk diluted wine or

kvas and snacked on bread or suhary. Their officers drunk tea with rum, and in winter a better quality wine.

There were also wounded in combat.

In a single battle could easily be wounded five or ten thousands men.

When the wounded reached a hospital after journeying for several days their condition

was pitiable. The wounded had their shirts torn up and black from dirtiness, which resulted

in epidemics and horrifying loss of men. It was given example when from one transport

out of 1.015 wounded and ill men only 85 returned ! (“Otechestvennaia Voina I Russkoie

Obschestvo 1812-1912” 1911, Vol III , part “Vozhdi armii”)

There were also wounded in combat.

In a single battle could easily be wounded five or ten thousands men.

When the wounded reached a hospital after journeying for several days their condition

was pitiable. The wounded had their shirts torn up and black from dirtiness, which resulted

in epidemics and horrifying loss of men. It was given example when from one transport

out of 1.015 wounded and ill men only 85 returned ! (“Otechestvennaia Voina I Russkoie

Obschestvo 1812-1912” 1911, Vol III , part “Vozhdi armii”)

The goals and general format of the Russian officer corps was the same as in the rest of

Europe. However the low level of professionalism and education in Russian society and hence in the

officer corps, little regard for individual, system of supression, bureaucratic corruption,

court intrigues and camarilla, made them inferior in some aspects (but not in bravery)

to officers from western European armies.

The goals and general format of the Russian officer corps was the same as in the rest of

Europe. However the low level of professionalism and education in Russian society and hence in the

officer corps, little regard for individual, system of supression, bureaucratic corruption,

court intrigues and camarilla, made them inferior in some aspects (but not in bravery)

to officers from western European armies.

Rather than working through the problems, Russian officers often retreated to hanging around

together smoking and drinking late into the night, perpetuating the irresponsibility. The drinking was probably the worst among cavalry officers.

When several hussar regiments quartered in one place their officers gathered and got drunk.

They liked to drink as they called it “in Polish style”, from very big glasses.

Rather than working through the problems, Russian officers often retreated to hanging around

together smoking and drinking late into the night, perpetuating the irresponsibility. The drinking was probably the worst among cavalry officers.

When several hussar regiments quartered in one place their officers gathered and got drunk.

They liked to drink as they called it “in Polish style”, from very big glasses.

Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov was born in 1745 in St Petersburg as the son of a lieutenant-general, military

engineer, retired general Illarion Matveevich Kutuzov who had served Tzar Peter the Great.

Chandler writes: "Kutuzov received a commission in the Russian artillery under Tsarina Catherine II.

He later transferred into the newly raised Jager or light infantry corps, which in due course he rose to command."

(Chandler - "Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars" pp 229-230)

Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov was born in 1745 in St Petersburg as the son of a lieutenant-general, military

engineer, retired general Illarion Matveevich Kutuzov who had served Tzar Peter the Great.

Chandler writes: "Kutuzov received a commission in the Russian artillery under Tsarina Catherine II.

He later transferred into the newly raised Jager or light infantry corps, which in due course he rose to command."

(Chandler - "Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars" pp 229-230)

When in 1812 Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief and arrived to the army he was

greeted by the entire army with great joy. Within two weeks he decided to give major

battle near Borodino in what has been described as the bloodiest battle in human

history up to that date.

When in 1812 Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief and arrived to the army he was

greeted by the entire army with great joy. Within two weeks he decided to give major

battle near Borodino in what has been described as the bloodiest battle in human

history up to that date.

Kutuzov realized that the Russian army would not survive another such battle and ordered

to leave Moscow and retreat. They have crossed the Moskva River, turned to the west and pitched camp in Tarutino.

At the same time Cossacks and hussars continued moving along the Ryazan Road misleading Murat's French cavalry.

When Murat discovered his error he did not retreat but made camp not far from the Russians in order to keep his eye on them.

Kutuzov ordered Bennigsen and Miloradovich to attack Murat with two battle groups stealthily crossing the forest in

the night. In the darkness most of the Russian troops got lost. By the morning only Cossacks reached the original destination,

suddenly attacked the French troops and captured the French camp with transports and cannons.

Since other Russian units came late the French were able to recover. When the Russians emerged from the forest they forced

Murat to retreat. The French suffered 4,500 killed, wounded and prisoners, the Russians

lost 1,200 dead.

Kutuzov realized that the Russian army would not survive another such battle and ordered

to leave Moscow and retreat. They have crossed the Moskva River, turned to the west and pitched camp in Tarutino.

At the same time Cossacks and hussars continued moving along the Ryazan Road misleading Murat's French cavalry.

When Murat discovered his error he did not retreat but made camp not far from the Russians in order to keep his eye on them.

Kutuzov ordered Bennigsen and Miloradovich to attack Murat with two battle groups stealthily crossing the forest in

the night. In the darkness most of the Russian troops got lost. By the morning only Cossacks reached the original destination,

suddenly attacked the French troops and captured the French camp with transports and cannons.

Since other Russian units came late the French were able to recover. When the Russians emerged from the forest they forced

Murat to retreat. The French suffered 4,500 killed, wounded and prisoners, the Russians

lost 1,200 dead.

The Russian army attacked the French at Malo-Yaroslavetz, this battle discouraged Napoleon

from continuing his march on the southern road to Smolensk. Napoleon unwillingly returned

on the route from which he came, a road now totally devastated. All the decisions of Kutuzov

earned him the title of "Old Fox" by Napoleon himself.

The Russian army attacked the French at Malo-Yaroslavetz, this battle discouraged Napoleon

from continuing his march on the southern road to Smolensk. Napoleon unwillingly returned

on the route from which he came, a road now totally devastated. All the decisions of Kutuzov

earned him the title of "Old Fox" by Napoleon himself.